The larynx (voice box) is an organ located in the anterior neck. It is a component of the respiratory tract, and has several important functions, including phonation, the cough reflex, and protection of the lower respiratory tract.

The structure of the larynx is primarily cartilaginous, and is held together by a series of ligaments and membranes. Internally, the laryngeal muscles move components of the larynx for phonation and breathing.

In this article, we will discuss the anatomy of the larynx – its location, structure, vasculature and innervation. We shall also consider its clinical relevance.

Anatomical Position and Relations

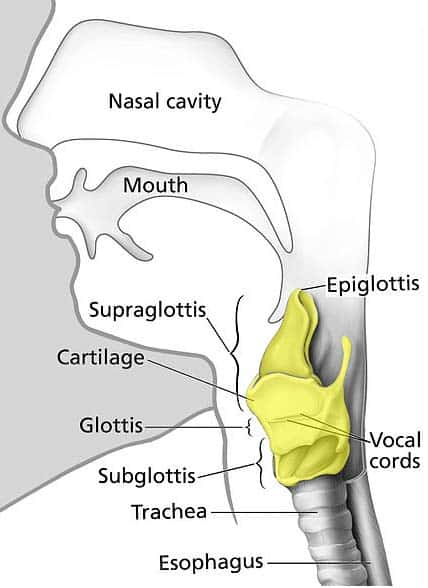

The larynx is located in the anterior compartment of the neck, suspended from the hyoid bone, and spanning between C3 and C6. It is continuous inferiorly with the trachea, and opens superiorly into the laryngeal part of the pharynx.

It is covered anteriorly by the infrahyoid muscles, and laterally by the lobes of the thyroid gland. The larynx is also closely related to the major blood vessels of neck, which ascend laterally to it.

Posterior to the larynx is the oesophagus. This is of clinical relevance during emergency intubation – as pressure can be applied to the cricoid cartilage of the larynx to occlude the oesophagus, and thus prevent regurgitation of gastric contents (known as cricoid pressure or Sellick’s manoeuvre).

Fig 1 -Anatomical position of the larynx (yellow) in the neck. It is continuous with the trachea inferiorly and the pharynx superiorly.

Anatomical Structure

The larynx is formed by a cartilaginous skeleton, which is held together by ligaments and membranes. The laryngeal muscles act to move the components of the larynx for phonation and breathing. More information about each of these structures can be found in their respective sections.

Anatomically, the internal cavity of the larynx can be divided into three sections:

- Supraglottis – From the inferior surface of the epiglottis to the vestibular folds (false vocal cords).

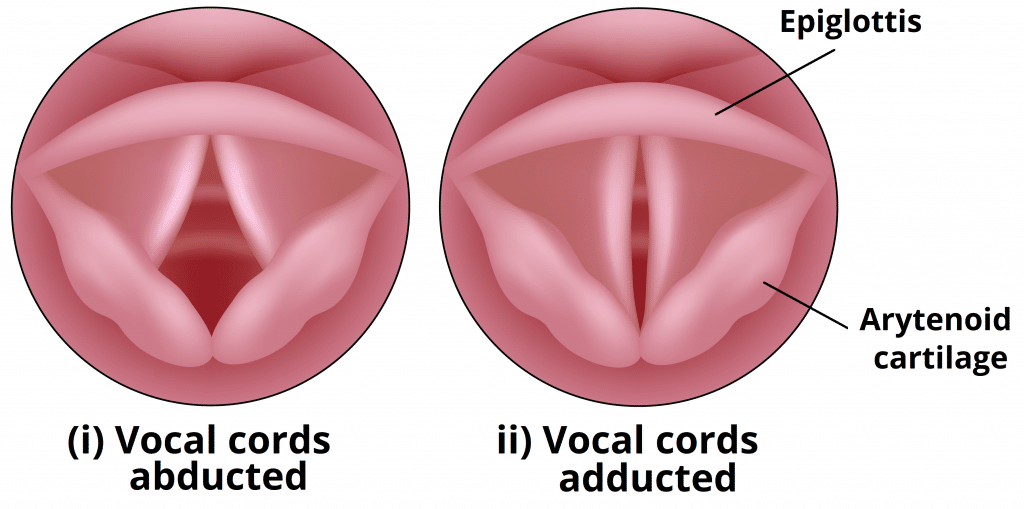

- Glottis – Contains vocal cords and 1cm below them. The opening between the vocal cords is known as rima glottidis, the size of which is altered by the muscles of phonation.

- Subglottis – From inferior border of the glottis to the inferior border of the cricoid cartilage.

The interior surface of the larynx is lined by pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium. An important exception to this is the true vocal cords, which are lined by a stratified squamous epithelium.

Vasculature

The arterial supply to the larynx is via the superior and inferior laryngeal arteries:

- Superior laryngeal artery – a branch of the superior thyroid artery (derived from the external carotid). It follows the internal branch of the superior laryngeal nerve into the larynx.

- Inferior laryngeal artery – a branch of the inferior thyroid artery (derived from the thyrocervical trunk). It follows the recurrent laryngeal nerve into the larynx.

Venous drainage is by the superior and inferior laryngeal veins. The superior laryngeal vein drains to the internal jugular vein via the superior thyroid, whereas the inferior laryngeal vein drains to the left brachiocephalic vein via the inferior thyroid vein.

Innervation

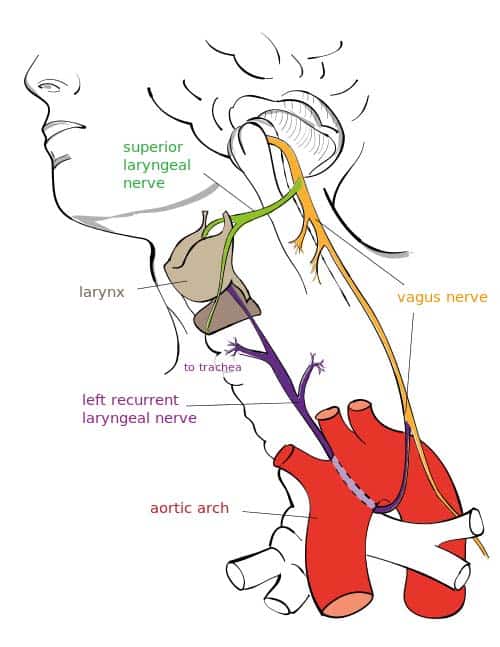

The larynx receives both motor and sensory innervation via branches of the vagus nerve:

- Recurrent laryngeal nerve – provides sensory innervation to the infraglottis, and motor innervation to all the internal muscles of larynx (except the cricothyroid).

- Superior laryngeal nerve – the internal branch provides sensory innervation to the supraglottis, and the external branch provides motor innervation to the cricothyroid muscle.

Fig 2 – Overview of the major branches of the vagus nerve

Clinical Relevance: Vocal Cord Paralysis

The vocal cords are responsible for the production of speech. Their movement is controlled by the intrinsic muscles of the larynx – the majority of which are innervated by the recurrent laryngeal nerve (an exception is the cricothyroid muscle; innervated by the external laryngeal nerve).

Due to its long course, the recurrent laryngeal nerve is susceptible to damage. Causes of RLN palsy include:

- Apical lung tumour

- Thyroid cancer

- Aortic aneurysm

- Cervical lymphadenopathy

- Iatrogenic (particularly during thyroid surgery due to the close relationship with the inferior thyroid artery).

In unilateral RLN palsy, one vocal cord is paralysed. The other vocal cord tends to compensate, and speech is not affected to a great degree, although the patient may experience hoarseness of voice. In cases of bilateral palsy, both vocal cords are paralysed in a position between adduction and abduction. Breathing is impaired, and phonation cannot occur.

In situations where the nerves are only partially damaged, the vocal folds become paralysed in a fully adducted position. If this occurs bilaterally, the rima glottidis (space between the vocal cords) is completely closed, and emergency surgical intervention is required to restore the airway.