The reproductive system is a collection of internal and external sex organs which work together for the purpose of sexual reproduction.

The development of these reproductive organs begins at an early stage in the embryo. There is a close link throughout with the development of the urinary system.

This article will look at the origins of both male and female sex organs; including the gonads, internal genitalia, and external genitalia.

The Gonads

Indifferent Stage

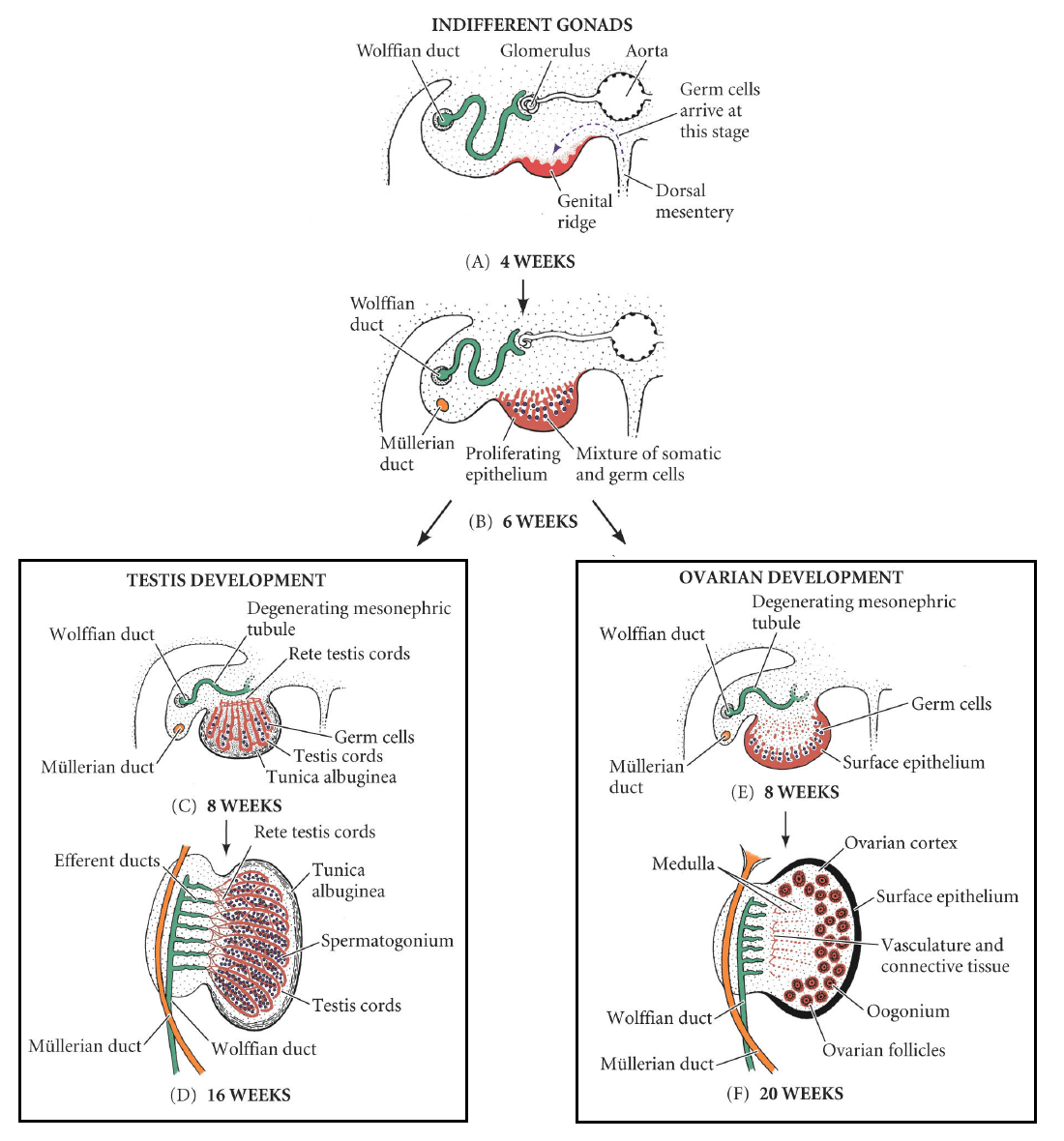

In the first stage of gonadal development, it is impossible to distinguish between the male and female gonad. Thus, it is known as the indifferent stage.

The gonads begin as genital ridges – a pair of longitudinal ridges derived from intermediate mesoderm and overlying epithelium. They initially do not contain any germ cells.

In the fourth week, germ cells begin to migrate from the endoderm lining of the yolk sac to the genital ridges, via the dorsal mesentary of the hindgut. They reach the genital ridges in the sixth week.

Simultaneously, the epithelium of the genital ridges proliferates and penetrates the intermediate mesoderm to form the primitive sex cords. The combination of germ cells and primitive sex cords forms the indifferent gonad – from which development into the testes or ovaries can occur.

Testes

In a male embryo, the XY sex chromosomes are present. The Y chromosome contains the SRY gene, which stimulates the development of the primitive sex cords to form testis (medullary) cords. The tunica albuginea, a fibrous connective tissue layer, forms around the cords.

A portion of the testis cords breaks off to form the future rete testis. The remaining cords contain two types of cells:

- Germ cells

- Sertoli cells (derived from the surface epithelium of the gland).

In puberty, these cords acquire a lumen and become the seminiferous tubules – the site within which sperm will be formed.

Located between the testis cords are the Leydig cells (derived from the intermediate mesoderm). In the eighth week, they begin production of testosterone – which drives differentiation of the internal and external genitalia.

Ovaries

In a female embryo, the XX sex chromosomes are present. As there is no Y chromosome, there is no SRY gene to influence development. Without it, the primitive sex cords degenerate and do not form the testis cords.

Instead, the epithelium of the gonad continues to proliferate, producing cortical cords. In the third month, these cords break up into clusters, surrounding each oogonium (germ cell) with a layer of epithelial follicular cells, forming a primordial follicle.

The Internal Genitalia

Indifferent Stage

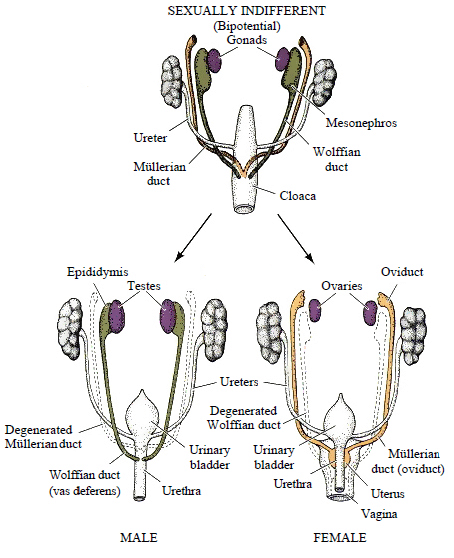

In the first weeks of urogenital development, all embryos have two pairs of ducts, both ending at the cloaca. These are the:

- Mesonephric (Wolffian) ducts

- Paramesonephric (Mullerian) ducts

Male

In the presence of testosterone (produced by the Leydig cells), the mesonephric ducts develop to form the primary male genital ducts. They give rise to the efferent ductules, epididymis, vas deferens and seminal vesicles.

Meanwhile, the paramesonephric ducts degenerate in the presence of anti-Mullerian hormone – produced by sertoli cells in the testes. Its developmental remnant is the appendix testis; a small portion of tissue located on the upper pole of each testicle, which has no physiological function.

Female

In the female, there are no Leydig cells to produce testosterone. In the absence of this hormone, the mesonephric ducts degenerate, leaving behind only a vestigial remnant – Gartner’s duct.

Equally, the absence of anti-Mullerian hormone also allows for development of the paramesonephric ducts. Initially, these ducts can be described as having three parts:

- Cranial – becomes the Fallopian tubes

- Horizontal – becomes the Fallopian tubes

- Caudal – fuses to form the uterus, cervix and upper 1/3 of the vagina.

The lower 2/3 of the vagina is formed by sinovaginal bulbs (derived from the pelvic part of the urogenital sinus).

Fig 2 – Development of the internal genitalia in the male and female.

Clinical Relevance: Bicornuate Uterus

Bicornate uterus is a relatively common structural defect. It occurs when there is incomplete fusion of the paramesonephric ducts.

This results in two distinct uterine horns, both opening into a single vagina. As it is asymptomatic, the condition is often only picked up on ultrasound scan during pregnancy.

This malformation is considered high-risk in pregnancy, as there is an associated risk of miscarriage and premature delivery.

Fig 3 – A bicornate uterus, formed by failure of the paramesonephric ducts to fuse fully.

External Genitalia

Indifferent Stage

The development of the external genitalia begins in the third week. Mesenchymal cells from the primitive streak migrate to the cloacal membrane to form a pair of cloacal folds.

Cranially, these folds fuse to form the genital tubercle. Caudally, they divide into the urethral folds (anterior) and anal folds (posterior).

Genital swellings develop either side of the urethral folds.

Male

The development of the indifferent genitalia into the male genitalia is driven by the presence of androgens from the testes, namely dihydrotestosterone (DHT).

There is rapid elongation of the genital tubercle, which becomes the phallus. The urethral folds are pulled to form the urethral groove – this extends along the caudal aspect of the phallus. The folds close over by the 4th month, forming the penile urethra.

The genital swellings become the scrotal swellings, moving caudally to eventually form the scrotum.

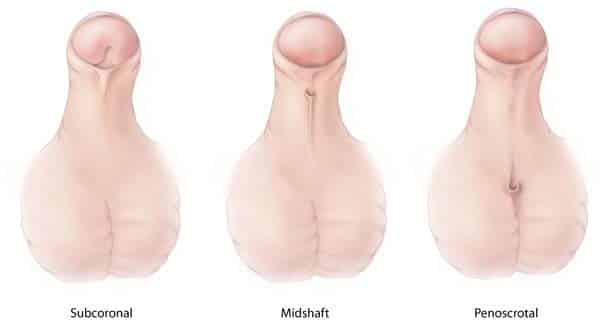

Clinical Relevance: Hypospadias

A condition in which there are one or more abnormal openings of the urethra along the inferior side of the penis. This is a result of incomplete closure of the urethral folds during development. Surgery is usually performed to correct the defect.

Female

Oestrogens in the female embryo are responsible for external genital development. The genital tubercle only elongates slightly to form the clitoris.

The urethral folds and genital swellings do not fuse, but instead form the labia minora and labia majora respectively.

The urogenital groove therefore remains open, forming the vestibule into which the urethra and vagina open.

Descent of the Gonads

While the gonads arise in the upper lumbar region, they are each tethered to the scrotum or labia by the gubernaculum – a ligamentous structure formed from mesenchyme.

Testes

As the body of the fetus grows, the testes become more caudal. They pass through the inguinal canal around the 28th week, and reach the scrotum by the 33rd week. During their descent, the testes retain their original blood supply, with the testicular arteries branching from the lumbar aorta.

The scrotal ligament is the adult remnant of the gubernaculum.

Ovaries

The ovaries initially migrate caudally in a similar fashion to the testes from their origin on the posterior abdominal wall. However they do not travel as far, reaching their final position just within the true pelvis.

The gubernaculum becomes the ovarian ligament and round ligament of the uterus.