The olfactory nerve (CN I) is the first and shortest cranial nerve. It is a special visceral afferent nerve, which transmits information relating to smell.

Embryologicallly, the olfactory nerve is derived from the olfactory placode (a thickening of the ectoderm layer), which also give rise to the glial cells which support the nerve.

In this article, we shall look at the anatomy of the olfactory nerve – its structure, anatomical course and clinical relevance.

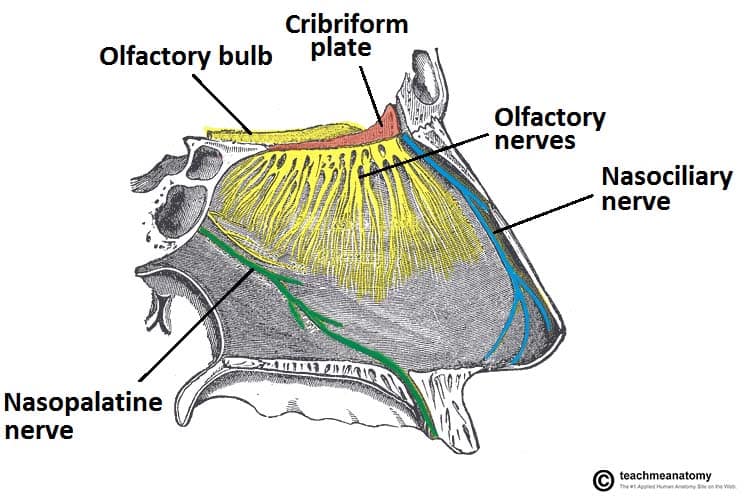

Fig 1 – Innervation of the nasal cavity. The olfactory nerve is responsible for the sense of smell. The nasociliary and nasopalatine nerves provide general sensation.

Anatomical Course

The anatomical course of the olfactory nerve describes the transmission of special sensory information from the nasal epithelium to the primary olfactory cortex of the brain.

Nasal Epithelium

The sense of smell is detected by olfactory receptors located within the nasal epithelium. Their axons (fila olfactoria) assemble into small bundles of true olfactory nerves, which penetrate the small foramina in the cribriform plate of the ethmoid bone and enter the cranial cavity.

Olfactory Bulb

Once in the cranial cavity, the fibres enter the olfactory bulb, which lies in the olfactory groove within the anterior cranial fossa.

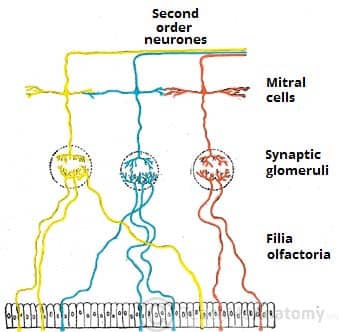

The olfactory bulb is an ovoid structure which contains specialised neurones, called mitral cells. The olfactory nerve fibres synapse with the mitral cells, forming collections known as synaptic glomeruli. From the glomeruli, second order nerves then pass posteriorly into the olfactory tract.

Olfactory Tract

The olfactory tract travels posteriorly on the inferior surface of the frontal lobe. As the tract reaches the anterior perforated substance (an area at the level of the optic chiasm) it divides into medial and lateral stria:

- Lateral stria – carries the axons to the primary olfactory cortex, located within the uncus of temporal lobe.

- Medial stria – carries the axons across the medial plane of the anterior commissure, where they meet the olfactory bulb of the opposite side.

The primary olfactory cortex sends nerve fibres to many other areas of the brain, notably the piriform cortex, the amygdala, olfactory tubercle and the secondary olfactory cortex. These areas are involved in the memory and appreciation of olfactory sensations.

Sensory Function

The sensory function of the olfactory nerve is achieved via the olfactory mucosa. This mucosal layer not only senses smell, but it also detects the more advanced aspects of taste.

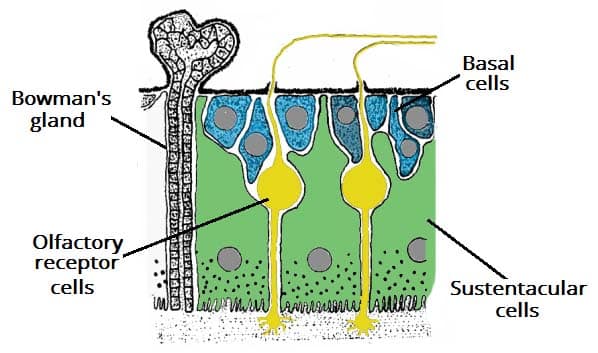

It is located in the roof of the nasal cavity and is composed of pseudostratified columnar epithelium which contains a number of cells:

- Basal cells – form the new stem cells from which the new olfactory cells can develop.

- Sustentacular cells – tall cells for structural support. These are analogous to the glial cells located in the CNS.

- Olfactory receptor cells – bipolar neurons which consist of two processes:

- Dendritic process projects to the surface of the epithelium, where they project a number of short cilia, the olfactory hairs, into the mucous membrane. These cilia react to odors in the air and stimulate the olfactory cells.

- Central process (also known as the axon) projects in the opposite direction through the basement membrane.

In addition to the epithelium, there are Bowman’s glands present in the mucosa, which secrete mucus.

Clinical Relevance: Anosmia

Anosmia is defined as the absence of the sense of smell. It can be temporary, permanent, progressive or congenital.

- Temporary anosmia can be caused by infection (e.g. meningitis) or by local disorders of the nose (e.g. common cold)

- Permanent anosmia can be caused by head injury, or tumours which occur in the olfactory groove (e.g. meningioma).

- Anosmia can also occur as a result of neurodegenerative conditions, such as Parkinson’s or Alzheimer’s disease. In these conditions, the anosmia is progressive and precedes motor symptoms but it is not often noticed by the patient.

- Anosmia is also a feature of a number of genetic conditions such as Kallmann syndrome (failure to start or finish puberty) and Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (defect in cilia causing it to be immobile)

Clinical Relevance: Olfactory Nerve Examination

Assessment of the olfactory nerve is an important part of a complete cranial nerve examination.

First, the patient should be asked if they have noticed any changes in their taste or sense of smell. Then each nostril should be tested, asking the patient to identify a certain smell (peppermint or coffee are often used). The eyes should be closed for this part of the examination.