The hip joint is a ball and socket synovial joint, formed by an articulation between the pelvic acetabulum and the head of the femur.

It forms a connection from the lower limb to the pelvic girdle, and thus is designed for stability and weight-bearing – rather than a large range of movement.

In this article, we shall look at the anatomy of the hip joint – its articulating surfaces, ligaments and neurovascular supply.

Structures of the Hip Joint

Articulating Surfaces

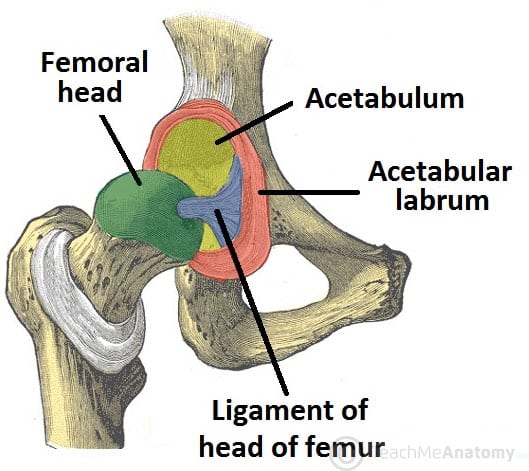

The hip joint consists of an articulation between the head of femur and acetabulum of the pelvis.

The acetabulum is a cup-like depression located on the inferolateral aspect of the pelvis. Its cavity is deepened by the presence of a fibrocartilaginous collar – the acetabular labrum. The head of femur is hemispherical, and fits completely into the concavity of the acetabulum.

Both the acetabulum and head of femur are covered in articular cartilage, which is thicker at the places of weight bearing.

The capsule of the hip joint attaches to the edge of the acetabulum proximally. Distally, it attaches to the intertrochanteric line anteriorly and the femoral neck posteriorly.

Fig 1 – The articulating surfaces of the hip joint – pelvic acetabulum and head of the femur.

Ligaments

The ligaments of the hip joint act to increase stability. They can be divided into two groups – intracapsular and extracapsular:

Intracapsular

The only intracapsular ligament is the ligament of head of femur. It is a relatively small structure, which runs from the acetabular fossa to the fovea of the femur.

It encloses a branch of the obturator artery (artery to head of femur), a minor source of arterial supply to the hip joint.

Extracapsular

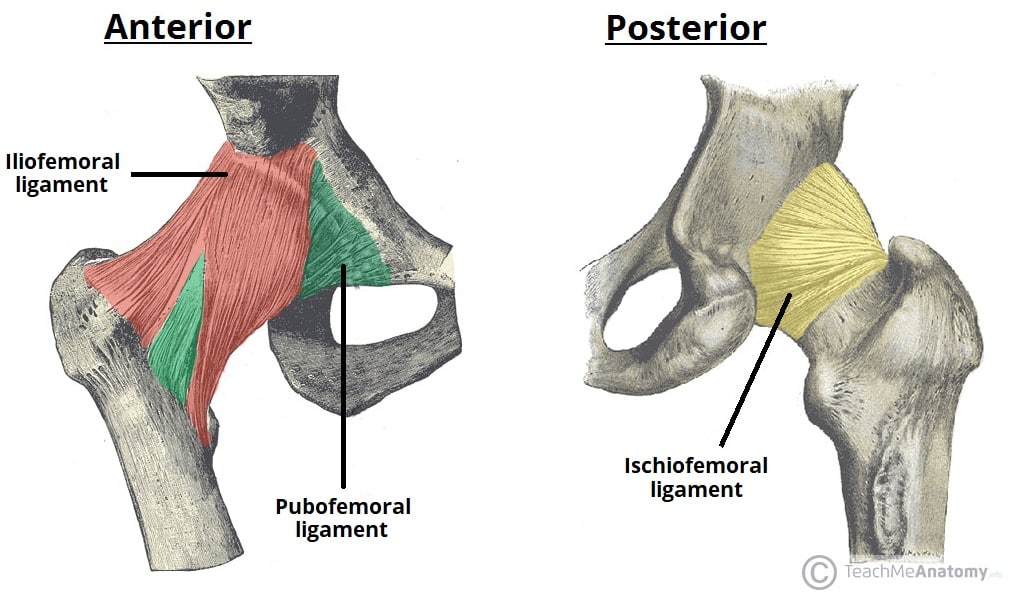

There are three main extracapsular ligaments, continuous with the outer surface of the hip joint capsule:

- Iliofemoral ligament – arises from the anterior inferior iliac spine and then bifurcates before inserting into the intertrochanteric line of the femur.

- It has a ‘Y’ shaped appearance, and prevents hyperextension of the hip joint. It is the strongest of the three ligaments.

- Pubofemoral – spans between the superior pubic rami and the intertrochanteric line of the femur, reinforcing the capsule anteriorly and inferiorly.

- It has a triangular shape, and prevents excessive abduction and extension.

- Ischiofemoral– spans between the body of the ischium and the greater trochanter of the femur, reinforcing the capsule posteriorly.

- It has a spiral orientation, and prevents hyperextension and holds the femoral head in the acetabulum.

Neurovascular Supply

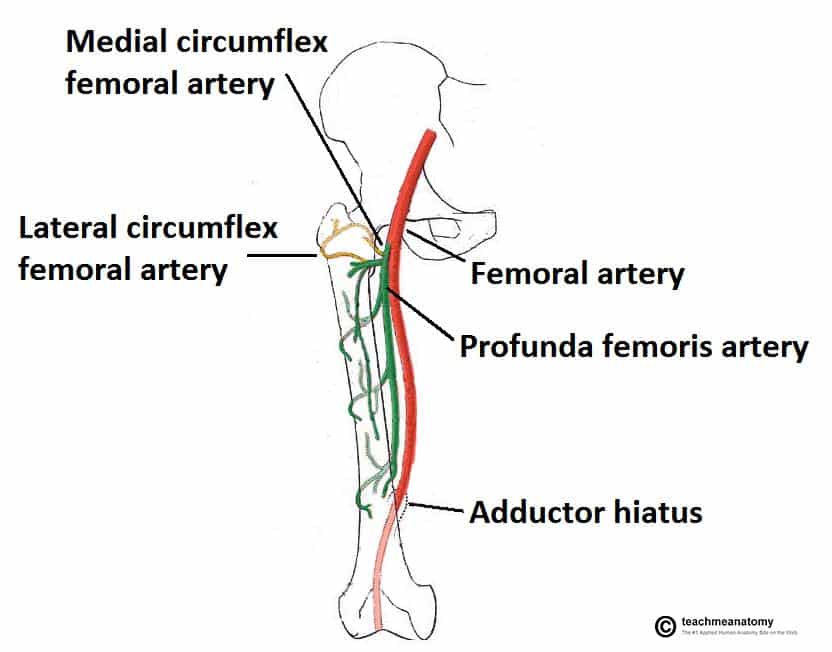

The arterial supply to the hip joint is largely via the medial and lateral circumflex femoral arteries – branches of the profunda femoris artery (deep femoral artery). They anastomose at the base of the femoral neck to form a ring, from which smaller arteries arise to supply the hip joint itself.

The medial circumflex femoral artery is responsible for the majority of the arterial supply (the lateral circumflex femoral artery has to penetrate through the thick iliofemoral ligament). Damage to the medial circumflex femoral artery can result in avascular necrosis of the femoral head.

The artery to head of femur and the superior/inferior gluteal arteries provide some additional supply.

The hip joint is innervated primarily by the sciatic, femoral and obturator nerves. These same nerves innervate the knee, which explains why pain can be referred to the knee from the hip and vice versa.

Fig 2 – The medial and lateral circumflex femoral arteries are the major blood supply to the hip joint.

Stabilising Factors

The primary function of the hip joint is to weight-bear. There are a number of factors that act to increase stability of the joint.

The first structure is the acetabulum. It is deep, and encompasses nearly all of the head of the femur. This decreases the probability of the head slipping out of the acetabulum (dislocation).

There is a horseshoe shaped fibrocartilaginous ring around the acetabulum which increases its depth, known as the acetabular labrum. The increase in depth provides a larger articular surface, further improving the stability of the joint.

The iliofemoral, pubofemoral and ischiofemoral ligaments are very strong, and along with the thickened joint capsule, provide a large degree of stability. These ligaments have a unique spiral orientation; this causes them to become tighter when the joint is extended.

In addition, the muscles and ligaments work in a reciprocal fashion at the hip joint:

- Anteriorly, where the ligaments are strongest, the medial flexors (located anteriorly) are fewer and weaker.

- Posteriorly, where the ligaments are weakest, the medial rotators are greater in number and stronger – they effectively ‘pull’ the head of the femur into the acetabulum.

Fig 3 – The extracapsular ligaments of the hip joint; ileofemoral, pubofemoral and ischiofemoral ligaments.

Movements and Muscles

The movements that can be carried out at the hip joint are listed below, along with the principle muscles responsible for each action:

- Flexion – iliopsoas, rectus femoris, sartorius, pectineus

- Extension – gluteus maximus; semimembranosus, semitendinosus and biceps femoris (the hamstrings)

- Abduction – gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, piriformis and tensor fascia latae

- Adduction – adductors longus, brevis and magnus, pectineus and gracilis

- Lateral rotation – biceps femoris, gluteus maximus, piriformis, assisted by the obturators, gemilli and quadratus femoris.

- Medial rotation – anterior fibres of gluteus medius and minimus, tensor fascia latae

The degree to which flexion at the hip can occur depends on whether the knee is flexed – this relaxes the hamstring muscles, and increases the range of flexion.

Extension at the hip joint is limited by the joint capsule and the iliofemoral ligament. These structures become taut during extension to limit further movement.

Clinical Relevance: Dislocation of the Hip Joint

Congenital Dislocation

Congenital hip dislocation occurs as a result of developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH). It occurs when the Acetabulum is shallow as a result of failure to develop properly in utero

Common clinical features include:

- Limited abduction at the hip joint

- Limb length discrepancy – the affected limb is shorter

- Asymmetrical gluteal or thigh skin folds

DDH is usually treated with a Pavlik harness. This holds the femoral head in the acetabular fossa and promotes normal development of the hip joint. Surgery is indicated in cases that do not respond to harness treatment.

Acquired Dislocation

Acquired dislocations of the hip joint are relatively uncommon, owing to the strength and stability of the joint. They usually occur as a result of trauma, but it can occur as a complication following Total Hip Replacement or hemiarthroplasty.

There are two main types of acquired hip dislocation; posterior and anterior:

- Posterior dislocation (90%) – the femoral head is forced posteriorly, and tears through the inferior and posterior part of the joint capsule, where it is at its weakest.

- The affected limb becomes shortened and medially rotated.

- The sciatic nerve runs posteriorly to the hip joint, and is at risk of injury (occurs in 10-20% of cases). This is often associated with anterior femoral head and posterior wall fractures

- Anterior dislocation (rare) – occurs as a consequence of traumatic extension, abduction and lateral rotation. The femoral head is displaced anteriorly and (usually) inferiorly in relation to the acetabulum.