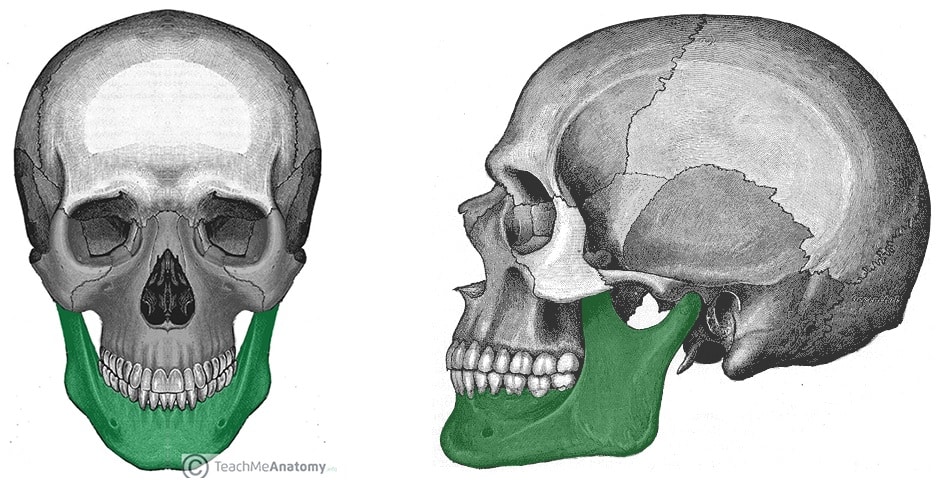

The mandible, located inferiorly in the facial skeleton, is the largest and strongest bone of the face.

It forms the lower jaw and acts as a receptacle for the lower teeth. It also articulates on either side with the temporal bone, forming the temporomandibular joint.

In this article, we will look at the anatomy and clinical importance of the mandible.

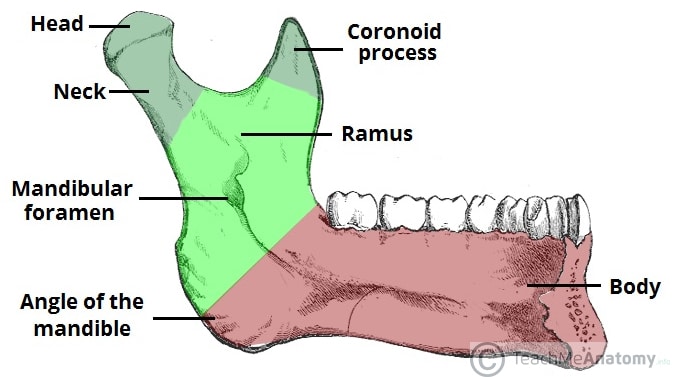

Fig 1

Anterior and lateral views of the mandible within the facial skeleton.

Pro Feature - 3D Model

Anatomical Structure

The mandible consists of a horizontal body (anteriorly) and two vertical rami (posteriorly). The body and the rami meet on each side at the angle of the mandible.

Body

The body of the mandible is curved, and shaped much like a horseshoe. It has two borders:

- Alveolar border (superior) – contains 16 sockets to hold the lower teeth.

- Base (inferior) – site of attachment for the digastric muscle medially

The body is marked in the midline by the mandibular symphysis. This is a small ridge of bone that represents the fusion of the two halves during development. The symphysis encloses a triangular eminence – the mental protuberance, which forms the shape of the chin.

Lateral to the mental protuberance is the mental foramen (below the second premolar tooth on either side). It acts as a passageway for neurovascular structures.

Rami

There are two mandibular rami, which project perpendicularly upwards from the angle of the mandible. Each ramus contains the following bony landmarks:

- Head – situated posteriorly, and articulates with the temporal bone to form the temporomandibular joint.

- Neck – supports the head of the ramus, and site of attachment of the lateral pterygoid muscle.

- Coronoid process – site of attachment of the temporalis muscle

The internal surface of the ramus is also marked by the mandibular foramen, which acts as a passageway for neurovascular structures.

Foramina

A foramen refers to any opening through which neurovascular structures can travel. The mandible is marked by two foramina.

The mandibular foramen is located on the internal surface of the ramus of the mandible. It serves as a conduit for the inferior alveolar nerve and inferior alveolar artery. They travel through the mandibular foramen, into the mandibular canal, and exit at the mental foramen.

The mental foramen is positioned on the external surface of the mandibular body, below the second premolar tooth. It allows the inferior alveolar nerve and artery to exit the mandibular canal. When the inferior alveolar nerve passes through the mental foramen, it becomes the mental nerve (innervates the skin of the lower lip and the front of the chin).

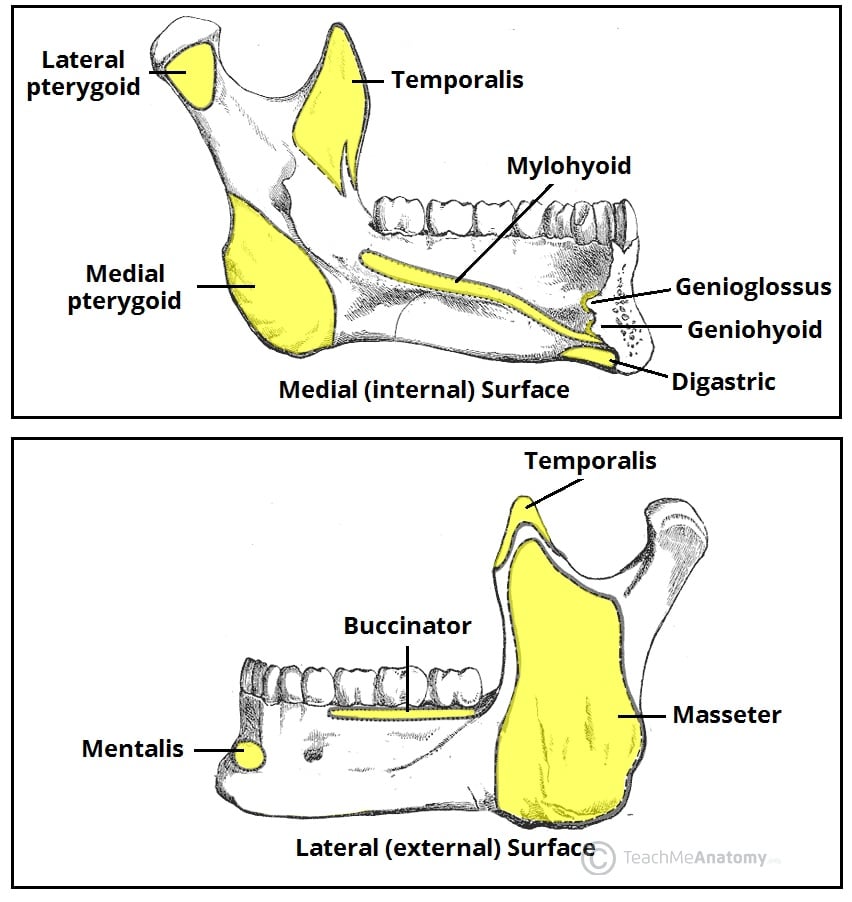

Muscular Attachments

The mandible serves as the attachment point for the various muscles, including the strong muscles of mastication.

- Mandibular body:

- External (lateral) surface – mentalis, buccinator, platysma, depressor labii inferioris, depressor anguli oris.

- Internal (medial) surface – genioglossus, geniohyoid, mylohyoid and digastric.

- Mandibular rami – masseter, temporalis, medial pterygoid and lateral pterygoid.

The temporalis muscle attaches to the coronoid process, and the masseter attaches to the rami. The lateral pterygoid inserts into the neck of the mandible, and the medial pterygoid inserts into the ramus near the angle of the mandible.

Articulations

The mandible articulates with the temporal bone to form the temporomandibular joint which is discussed in more detail here.

Clinical Relevance

Fractures of the Mandible

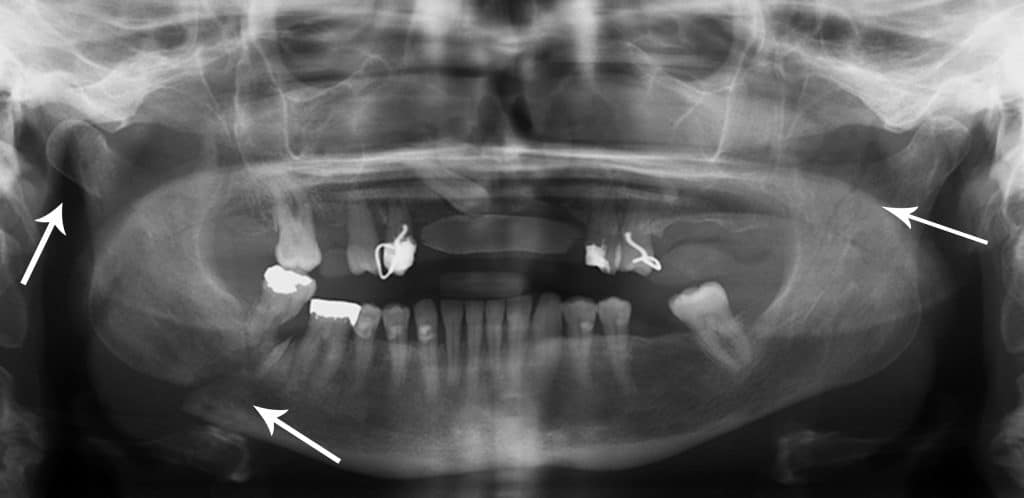

A mandibular fracture rarely occurs in isolation. Much like fractures of the pelvic brim, a fracture on one side is frequently associated with a fracture on the contralateral side.

Therefore, if one fracture is observed, another should be searched for. For example, a fractured neck of the mandible is often observed in conjunction with a fracture of the contralateral mandibular body.

The characteristics of mandibular fractures are as follows:

- Fractures of the coronoid process are uncommon and usually singular.

- Fractures of the neck of the mandible are often transverse and usually accompanied with dislocation of the temporomandibular joint.

- Fractures of the angle of the mandible are usually oblique and may involve the alveolus of the 3rd molar.

- Fractures of the body of the mandible frequently pass through the canine tooth.