The sternoclavicular joint is an articulation between the clavicle and the manubrium of the sternum.

It is a saddle-type synovial joint which acts to link the upper limb with the trunk.

In this article, we will examine the anatomy of the sternoclavicular joint – its structure, neurovascular supply, and clinical considerations.

Anatomical Structure

Articulating Surfaces

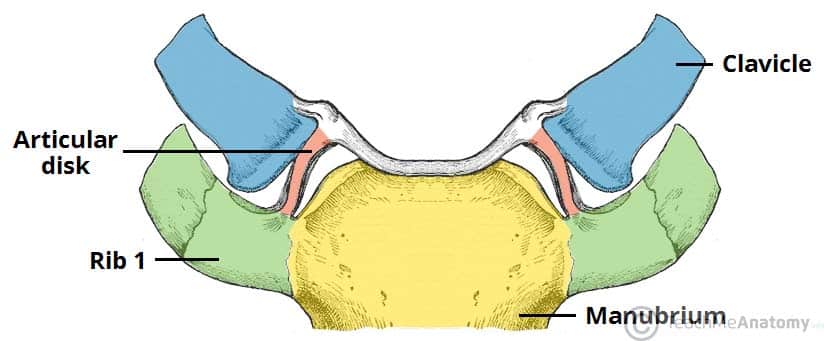

The sternoclavicular joint is formed by an articulation between three structures:

- Sternal end of the clavicle

- Manubrium of the sternum

- First costal cartilage (cartilage associated with the first rib)

The articular surfaces are covered with fibrocartilage (as opposed to hyaline cartilage, present in the majority of synovial joints). The joint is separated into two compartments by a fibrocartilaginous articular disc.

Joint Capsule

The joint capsule of the sternoclavicular joint extends to the borders of the articular surfaces.

It is lined internally by a synovial membrane, which produces synovial fluid to reduce friction between the articulating structures.

Ligaments

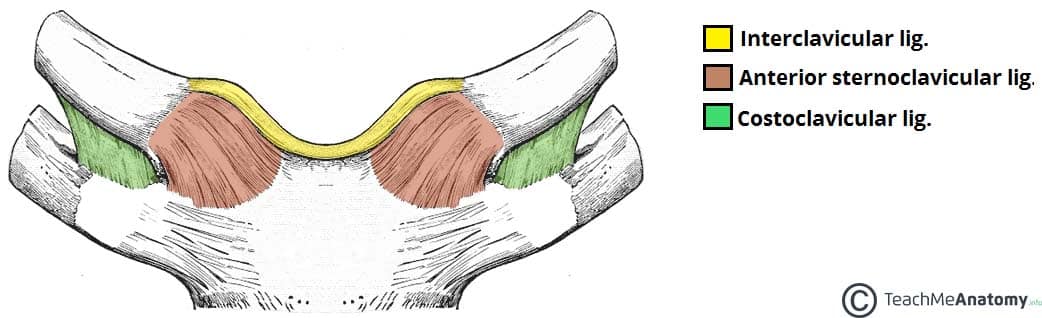

The ligaments of the sternoclavicular joint provide much of its stability. There are four main ligaments:

- Sternoclavicular ligaments (anterior and posterior) – reinforces the joint capsule anteriorly and posteriorly.

- Interclavicular ligament – attaches to the sternal end of both clavicles and reinforces the joint capsule superiorly.

- Costoclavicular ligament – attaches the first rib and costal cartilage to the inferior surface of the clavicle.

- It is the main stabilising force for the joint, resisting elevation of the pectoral girdle.

Movements

The sternoclavicular joint has a large degree of mobility, with several movements possible:

- Elevation of the shoulders – shrugging the shoulders or abducting the arm over 90º

- Depression of the shoulders – drooping shoulders or extending the arm at the shoulder behind the body

- Protraction of the shoulders – moving the shoulder girdle anteriorly

- Retraction of the shoulders – moving the shoulder girdle posteriorly

- Rotation – when the arm is raised over the head, the clavicle rotates passively as the scapula rotates.

Mobility and Stability

The sternoclavicular joint is required to be both mobile (to accommodate the movements of the upper limb) and strong (to form a stable connection between the upper limb and the trunk).

Here we will consider the factors which contribute to both its mobility and its stability:

Mobility:

- Type of joint – being a saddle joint it can move in two axes.

- Articular disc – this allows the clavicle and the manubrium to slide over each other more freely, allowing for rotation and movement in a third axis.

Stability:

- Joint capsule – thick and strong.

- Ligaments – particularly the costoclavicular ligament, which transfers forces from the clavicle to the manubrium (via the costal cartilage).

Blood Supply

The arterial supply to the sternoclavicular joint is from the internal thoracic artery and the suprascapular artery.

Innervation

The sternoclavicular joint is supplied by the medial supraclavicular nerve (C3 and C4) and the nerve to subclavius (C5 and C6).

Clinical Relevance: Dislocation of the Sternoclavicular Joint

Dislocation of the sternoclavicular joint is rare and requires significant force. The costoclavicular ligament and the articular disc are highly effective at absorbing and transmitting forces away from the joint into the sternum.

There are two major types of dislocation:

- Anterior dislocations (more common) – result from a blow to the anterior shoulder which rotates the shoulder backwards.

- Posterior dislocations (less common) – result from a force driving the shoulder forwards or from direct impact to the joint.

In adolescents, the epiphyseal growth plate of the sternal end of the clavicle has not fully closed. In this population, the dislocation is usually accompanied by a fracture through the plate.