The infratemporal fossa is a complex area located at the base of the skull, deep to the masseter muscle.

It is closely associated with both the temporal and pterygopalatine fossae and acts as a conduit for neurovascular structures entering and leaving the cranial cavity.

In this article, we shall look at the anatomy of the infratemporal fossa – its borders, contents and clinical correlations

Borders

The infratemporal fossa can be said to have a wedge shape. It is located deep to the masseter muscle and zygomatic arch (to which the masseter attaches). The fossa is closely associated with both the pterygopalatine fossa, via the pterygomaxillary fissure, and also communicates with the temporal fossa, which lies superiorly.

The boundaries of this complex structure consists of both bone and muscle:

- Lateral – condylar process and ramus of the mandible bone

- Medial – lateral pterygoid plate; tensor veli palatine, levator veli palatine and superior constrictor muscles

- Anterior – posterior border of the maxillary sinus

- Posterior – carotid sheath

- Roof – greater wing of the sphenoid bone

- Floor – medial pterygoid muscle

The roof of the infratemporal fossa, formed by the greater wing of the sphenoid bone, provides an important passage for the neurovascular structures transmitted through the foramen ovale and spinosum. Among these are the mandibular branch of the trigeminal nerve and the middle meningeal artery.

Fig 1 – The bony features of the infratemporal fossa. The ramus of the mandible has been removed in this image.

Contents

The infratemporal fossa acts as a pathway for neurovascular structures passing to and from the cranial cavity, pterygopalatine fossa and temporal fossa. It also contains some of the muscles of mastication. In fact, the lateral pterygoid splits the fossa contents in half – the branches of the mandibular nerve lay deep to the muscle, while the maxillary artery is superficial to it.

Muscles

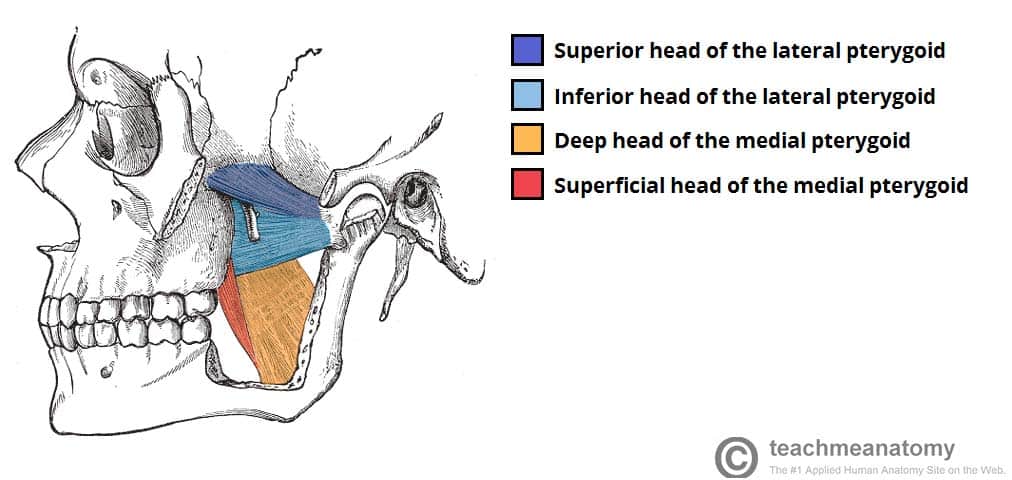

The infratemporal fossa is associated with the muscles of mastication. The medial and lateral pterygoids are located within the fossa itself, whilst the masseter and temporalis muscles insert and originate into the borders of the fossa.

Nerves

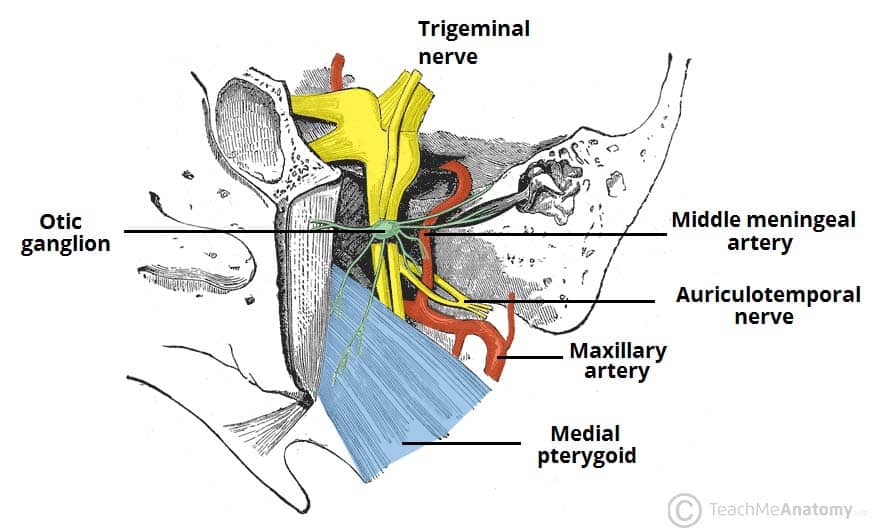

The infratemporal fossa forms an important passage for a number of nerves originating in the cranial cavity (figure 1.2):

- Mandibular nerve – a branch of the trigeminal nerve (CN V). It enters the fossa via the foramen ovale, giving rise to motor and sensory branches. The sensory branches continue inferiorly to provide innervation to some of the cutaneous structures of the face.

- Auriculotemporal, buccal, lingual and inferior alveolar nerves – sensory branches of the trigeminal nerve.

- Chorda tympani – a branch of the facial nerve (CN VII). It follows the anatomical course of the lingual nerve and provides taste innervation to the anterior 2/3 of the tongue.

- Otic ganglion – a parasympathetic collection of neurone cell bodies. Nerve fibres leaving this ganglion ‘hitchhike’ along the auriculotemporal nerve to reach the parotid gland.

Vasculature

The infratemporal fossa contains several vascular structures:

- Maxillary artery – the terminal branch of the external carotid artery. It travels through the infratemporal fossa.

- Within the fossa, it gives rise to the middle meningeal artery, which passes through the superior border via the foramen spinosum.

- Pterygoid venous plexus – drains the eye and is directly connected to the cavernous sinus.

- It provides a potential route by which infections of the face can spread intracranially.

- Maxillary vein

- Middle meningeal vein

Clinical Relevance – Fractures of the Pterion

The pterion is an important structure in cranial anatomy. It is the point where the temporal, parietal, frontal and sphenoid bones meet and the skull is at its weakest. Trauma in this region can lead to an extradural haematoma as the middle meningeal artery (MMA) lies deep to it.

An extradural haematoma causes a dangerous increase in intra-cranial pressure, which can lead to herniation of brain tissue and ischaemia.

The increase in intra-cranial pressure causes a variety of symptoms; nausea, vomiting, seizures, bradycardia and limb weakness. It is treated by diuretics in minor cases, and drilling burr holes into the skull in the more extreme haemorrhages.