The elbow is the joint connecting the upper arm to the forearm. It is classed as a hinge-type synovial joint.

In this article, we shall look at the anatomy of the elbow joint – its articulating surfaces, movements, stability, and the clinical relevance.

Structures of the Elbow Joint

Articulating Surfaces

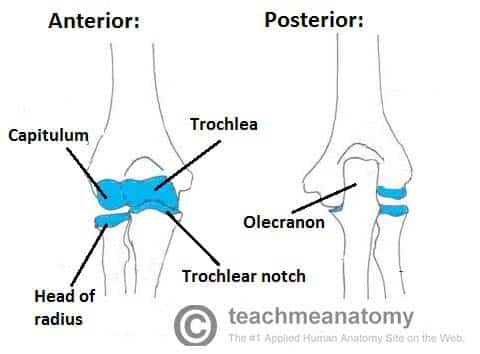

The elbow joint consists of two separate articulations:

- Trochlear notch of the ulna and the trochlea of the humerus

- Head of the radius and the capitulum of the humerus

Note: The proximal radioulnar joint is found within same joint capsule of the elbow, but most resources consider it as a separate articulation.

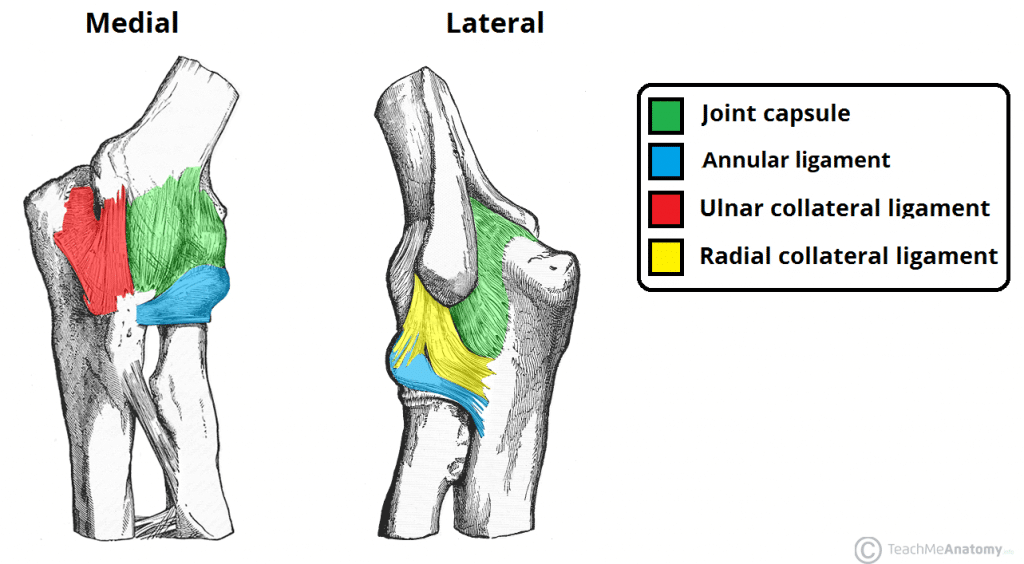

Fig 1 – Anterior and posterior views of the articulations of the elbow joint

Joint Capsule and Bursae

Like all synovial joints, the elbow joint has a capsule enclosing the joint. This is strong and fibrous, strengthening the joint. The joint capsule is thickened medially and laterally to form collateral ligaments, which stabilise the flexing and extending motion of the arm.

A bursa is a sac-like structure containing a small amount of synovial fluid. It functions to decrease friction between tendons, bone, and skin during movement. There are many bursae in the elbow, but only a few have clinical importance:

- Intratendinous olecranon – located within the tendon of the triceps brachii.

- Subtendinous olecranon – between the olecranon and the tendon of the triceps brachii, reducing friction between the two structures during extension and flexion of the arm.

- Subcutaneous olecranon bursa – between the olecranon and the overlying connective tissue (implicated in olecranon bursitis).

Ligaments

The joint capsule of the elbow is strengthened by ligaments medially and laterally.

The radial collateral ligament is found on the lateral side of the joint, extending from the lateral epicondyle, and blending with the annular ligament of the radius (a ligament from the proximal radioulnar joint).

The ulnar collateral ligament originates from the medial epicondyle, and attaches to the coronoid process and olecranon of the ulna.

Blood Supply

The elbow joint receives a rich arterial supply from a surrounding network of vessels, which is formed by branches of the brachial artery.

Innervation

The elbow joint is innervated by branches of the medial, musculocutaneous, radial and ulnar nerves.

Movements

The orientation of the bones forming the elbow joint produces a hinge type synovial joint, which allows for extension and flexion of the forearm:

- Extension – triceps brachii and anconeus

- Flexion – brachialis, biceps brachii, brachioradialis

Note – pronation and supination do not occur at the elbow – they are produced at the nearby radioulnar joints.

Clinical Relevance: Injuries to the Elbow Joint

Bursitis

Subcutaneous bursitis: Repeated friction and pressure on the bursa can cause it to become inflamed. Because this bursa lies relatively superficially, it can also become infected (e.g. skin laceration from a fall on the elbow)

Subtendinous bursitis: This is caused by repeated flexion and extension of the forearm, commonly seen in assembly line workers. Usually flexion is more painful as more pressure is put on the bursa.

Dislocation

An elbow dislocation usually occurs when a young child falls on a hand with the elbow flexed. The distal end of the humerus is driven through the weakest part of the joint capsule, which is the anterior side. The ulnar collateral ligament is usually torn and there can also be ulnar nerve involvement

Most elbow dislocations are posterior, and it is important to note that elbow dislocations are named by the position of the ulna and radius, not the humerus.

Epicondylitis (Tennis elbow or Golfer’s elbow)

Most of the flexor and extensor muscles in the forearm have a common tendinous origin. The flexor muscles originate from the medial epicondyle, and the extensor muscles from the lateral. Sportspersons can develop an overuse strain of the common tendon – which results in pain and inflammation around the area of the affected epicondyle.

Typically, tennis players experience pain in the lateral epicondyle from the common extensor origin. Golfers experience pain in the medial epicondyle from the common flexor origin. This is easily remembered as golfers aim for the ‘middle’ of the fairway, while tennis players aim for the ‘lateral’ line of the court!

Supracondylar Fracture

A supracondylar fracture usually occurs due to a fall onto on outstretched, extended hand in a child (95%) but more rarely can occur by a direct impact onto a flexed elbow. It is typically a transverse fracture, spanning between the two epicondyles in the relatively weak epicondylar region formed by the olecranon fossa and coronoid fossa which lie opposite each other in the distal humerus.

Direct damage, or swelling can cause the interference to the blood supply of the forearm via the brachial artery. The resulting ischaemia can cause Volkmann’s ischaemic contracture – uncontrolled flexion of the hand, as flexors muscles become fibrotic and short. There also can be damage to the medial, ulnar or radial nerves. As a result, the neurovascular examination and documentation of all patients presenting with these injuries is vital. Sometimes, the blood supply can be interrupted acutely leading to a ‘pale, pulseless’ limb often in a child, usually requiring emergency surgery.