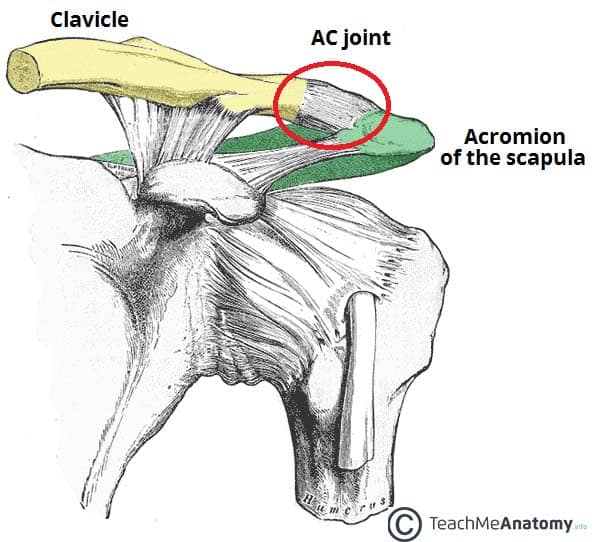

The acromioclavicular joint is an articulation in the shoulder region between the clavicle and the acromion of the scapula.

It is a plane type synovial joint.

In this article, we shall look at the anatomy of the acromioclavicular joint – its anatomical structure, neurovascular supply and any clinical correlations.

Anatomical Structure

Articulating Surfaces

The acromioclavicular joint consists of an articulation between the lateral end of the clavicle and the acromion of the scapula.

It has two atypical features:

- Articular surfaces of the joint are lined with fibrocartilage – as opposed to hyaline cartilage.

- Joint cavity is partially divided by an articular disc – a wedge of fibrocartilage suspended from the upper part of the capsule.

Joint Capsule

The joint capsule of the acromioclavicular joint encloses the two articular surfaces. It consists of a loose layer of fibrous tissue, which is lined internally by a synovial membrane.

The posterior aspect of the joint capsule is reinforced by fibres from the trapezius muscle.

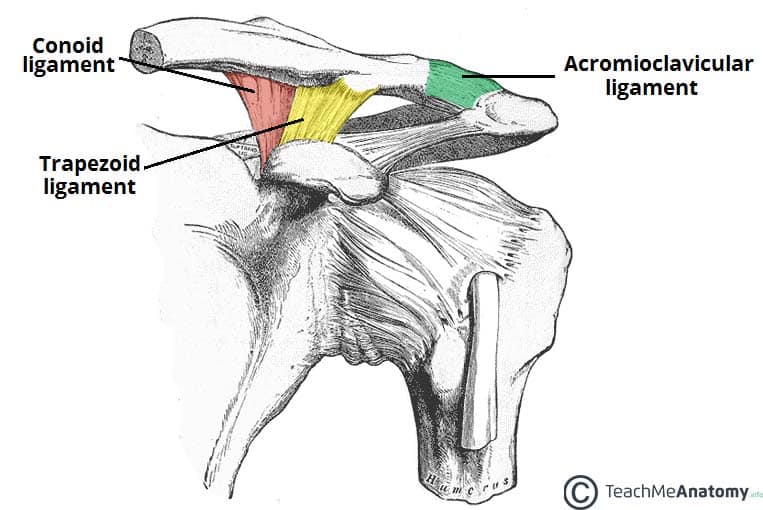

Ligaments

There are three main ligaments that strengthen and stabilise the acromioclavicular joint:

- Acromioclavicular ligament – runs horizontally from the acromion to the lateral clavicle. It covers the joint capsule, reinforcing its superior aspect.

- Conoid ligament – runs vertically from the coracoid process of the scapula to the conoid tubercle of the clavicle.

- Trapezoid ligament – runs from the coracoid process of the scapula to the trapezoid line of the clavicle.

The conoid and trapezoid ligaments are collectively known as the coracoclavicular ligament. It is a very strong structure, effectively suspending the weight of the upper limb from the clavicle.

Movements

The acromioclavicular joint allows a gliding movement in the superior/inferior and anteroposterior planes, along with a small amount of axial rotation.

As no muscle acts directly on the joint, all movements are passive, and are initiated by movement at other joints

Blood Supply

The arterial supply to the acromioclavicular joint is via the:

- Suprascapular artery – arises from the subclavian artery at the thyrocervical trunk.

- Thoracoacromial artery – arises from the axillary artery.

The venous drainage accompanies the major arteries.

Innervation

The acromioclavicular joint is innervated by articular branches of the suprascapular and lateral pectoral nerves. They both arise directly from the brachial plexus.

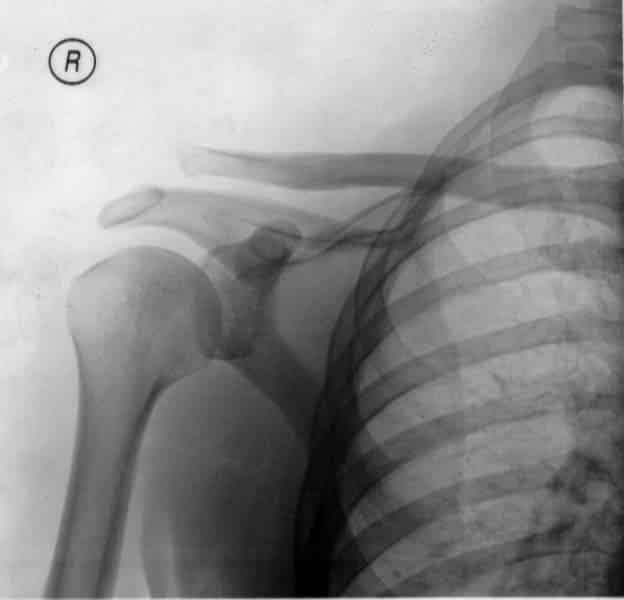

Clinical Relevance – Acromioclavicular Dislocation

Acromioclavicular joint dislocation (also known as a separated shoulder) occurs when the two articulating surfaces of the joint are separated.

It most commonly occurs from a direct blow to the joint, or a fall on an outstretched hand.

The injury is more serious if ligamental rupture occurs (acromioclavicular or coracoclavicular). If the coracoclavicular ligament is torn, the weight of the upper limb is not supported, and the shoulder drops inferiorly.

Management of AC joint dislocation is dependent on injury severity and impact on quality of life. The treatment options range from ice and rest, to ligament reconstruction surgery.

Note: this injury is not to be confused with shoulder dislocation – an injury affecting the glenohumeral joint.