The aorta is the largest artery in the body, initially being an inch wide in diameter. It receives the cardiac output from the left ventricle and supplies the body with oxygenated blood via the systemic circulation.

The aorta can be divided into four sections: the ascending aorta, the aortic arch, the thoracic (descending) aorta and the abdominal aorta. It terminates at the level of L4 by bifurcating into the left and right common iliac arteries. The aorta classified as a large elastic artery, and more information on its internal structure can be found here.

In this article we will look at the anatomy of the aorta – its anatomical course, branches and clinical correlations.

Ascending Aorta

The ascending aorta arises from the aortic orifice from the left ventricle and ascends to become the aortic arch. It is 2 inches long in length and travels with the pulmonary trunk in the pericardial sheath.

Branches

The left and right aortic sinuses are dilations in the ascending aorta, located at the level of the aortic valve. They give rise to the left and right coronary arteries that supply the myocardium.

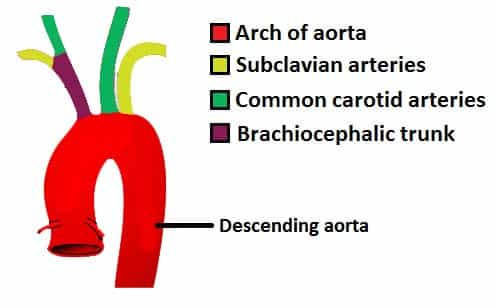

Aortic Arch

The aortic arch is a continuation of the ascending aorta and begins at the level of the second sternocostal joint. It arches superiorly, posteriorly and to the left before moving inferiorly.

The aortic arch ends at the level of the T4 vertebra. The arch is still connected to the pulmonary trunk by the ligamentum arteriosum (remnant of the foetal ductus arteriosus).

Branches

There are three major branches arising from the aortic arch. Proximal to distal:

- Brachiocephalic trunk: The first and largest branch that ascends laterally to split into the right common carotid and right subclavian arteries. These arteries supply the right side of the head and neck, and the right upper limb.

- Left common carotid artery: Supplies the left side of the head and neck.

- Left subclavian artery: Supplies the left upper limb.

Clinical Relevance: Coarctation of the Aorta

Coarctation of the aorta refers to narrowing of the vessel, usually at the insertion of the ligamentum arteriosum (former ductus arteriosus). It is a congenital condition. The narrow vessel has an increased resistance to blood flow, which increases the after-load for the left ventricle – leading to left ventricular hypertrophy.

Blood supply to the head, neck and upper limbs is not compromised as the vessels that supply them emerge proximal to the coarctation. However, blood supply to the rest of the body is reduced. This results in a weak, delayed femoral pulse which presents clinically as radio-femoral delay.

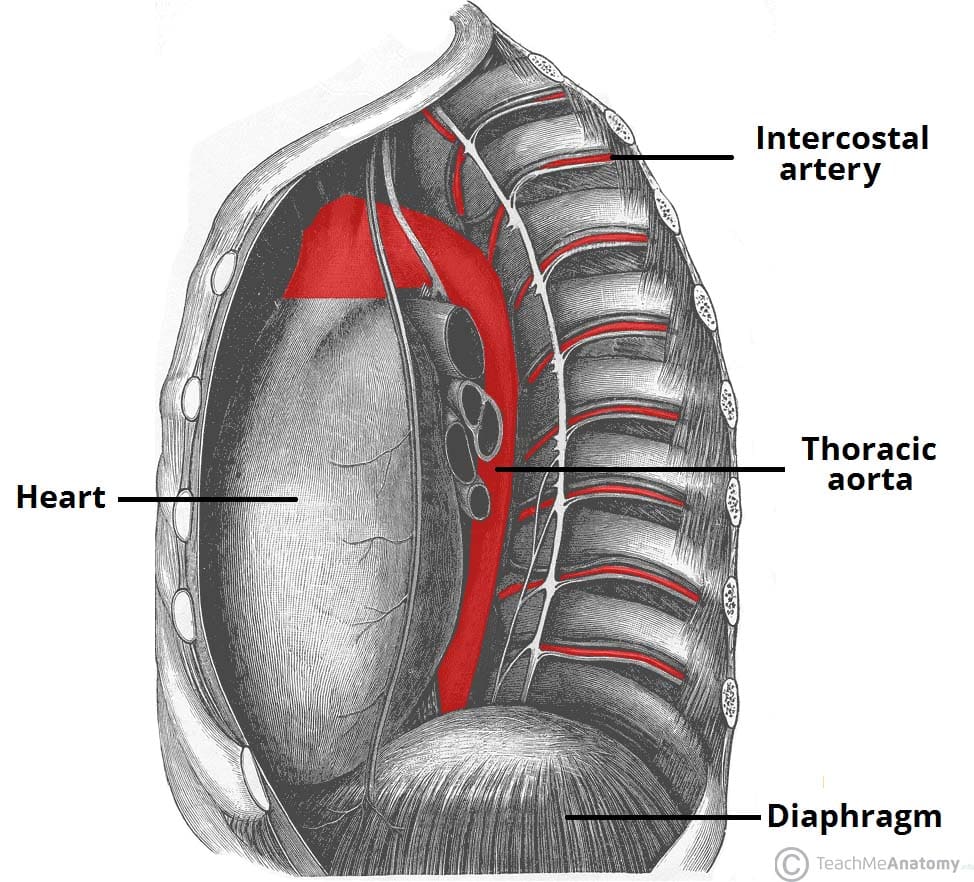

Thoracic Aorta

The thoracic (descending) aorta spans from the level of T4 to T12. Continuing from the aortic arch, it initially begins to the left of the vertebral column but approaches the midline as it descends. It leaves the thorax via the aortic hiatus in the diaphragm, and becomes the abdominal aorta.

Branches

In descending order:

- Bronchial arteries: Paired visceral branches arising laterally to supply bronchial and peribronchial tissue and visceral pleura. However, most commonly, only the paired left bronchial artery arises directly from the aorta whilst the right branches off usually from the third posterior intercostal artery.

- Mediastinal arteries: Small arteries that supply the lymph glands and loose areolar tissue in the posterior mediastinum.

- Oesophageal arteries: Unpaired visceral branches arising anteriorly to supply the oesophagus.

- Pericardial arteries: Small unpaired arteries that arise anteriorly to supply the dorsal portion of the pericardium.

- Superior phrenic arteries: Paired parietal branches that supply the superior portion of the diaphragm.

- Intercostal and subcostal arteries: Small paired arteries that branch off throughout the length of the posterior thoracic aorta. The 9 pairs of intercostal arteries supply the intercostal spaces, with the exception of the first and second (they are supplied by a branch from the subclavian artery). The subcostal arteries supply the flat abdominal wall muscles.

Fig 3 – Lateral view of the thoracic aorta, with the intercostal branches shown.

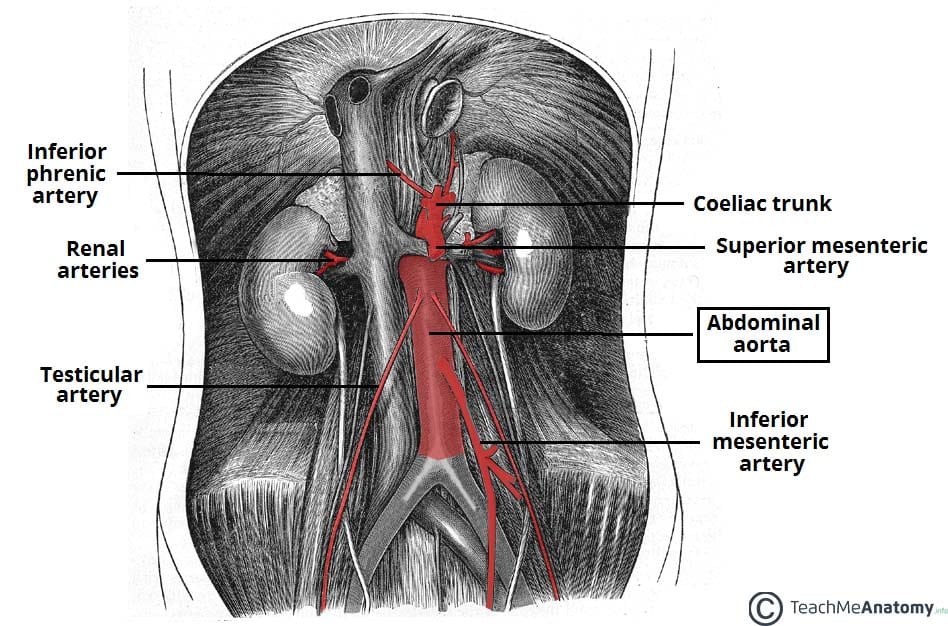

Abdominal Aorta

The abdominal aorta is a continuation of the thoracic aorta beginning at the level of the T12 vertebrae. It is approximately 13cm long and ends at the level of the L4 vertebra. At this level, the aorta terminates by bifurcating into the right and left common iliac arteries that supply the lower body.

Branches

In descending order:

- Inferior phrenic arteries: Paired parietal arteries arising posteriorly at the level of T12. They supply the diaphragm.

- Coeliac artery: A large, unpaired visceral artery arising anteriorly at the level of T12. It is also known as the celiac trunk and supplies the liver, stomach, abdominal oesophagus, spleen, the superior duodenum and the superior pancreas.

- Superior mesenteric artery: A large, unpaired visceral artery arising anteriorly, just below the celiac artery. It supplies the distal duodenum, jejuno-ileum, ascending colon and part of the transverse colon. It arises at the lower level of L1.

- Middle suprarenal arteries: Small paired visceral arteries that arise either side posteriorly at the level of L1 to supply the adrenal glands.

- Renal arteries: Paired visceral arteries that arise laterally at the level between L1 and L2. They supply the kidneys.

- Gonadal arteries: Paired visceral arteries that arise laterally at the level of L2. Note that the male gonadal artery is referred to as the testicular artery and in females, the ovarian artery.

- Inferior mesenteric artery: A large, unpaired visceral artery that arises anteriorly at the level of L3. It supplies the large intestine from the splenic flexure to the upper part of the rectum.

- Median sacral artery: An unpaired parietal artery that arises posteriorly at the level of L4 to supply the coccyx, lumbar vertebrae and the sacrum.

- Lumbar arteries: There are four pairs of parietal lumbar arteries that arise posterolaterally between the levels of L1 and L4 to supply the abdominal wall and spinal cord.

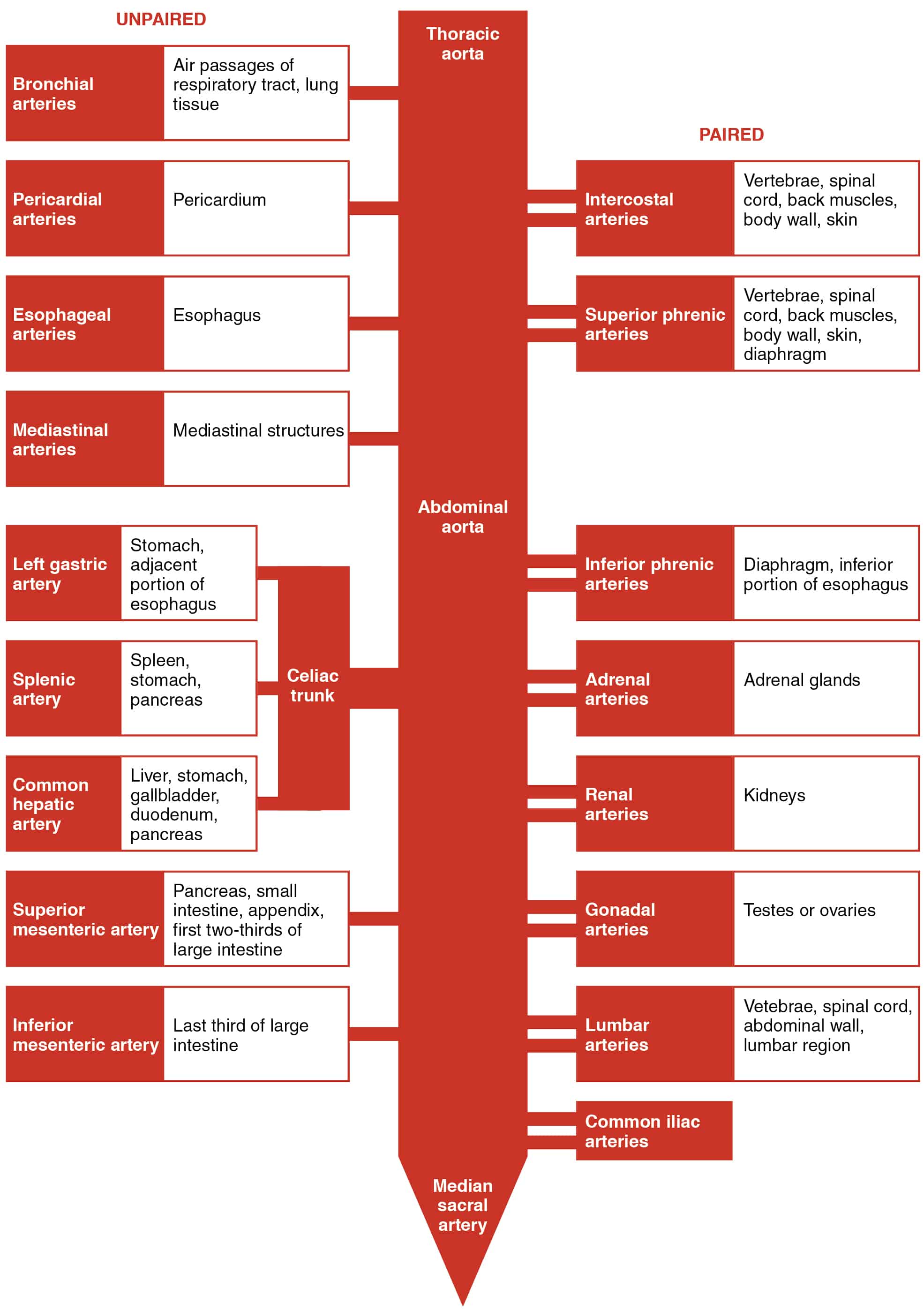

Fig 5 – Schematic of the branches of the thoracic and abdominal aorta.

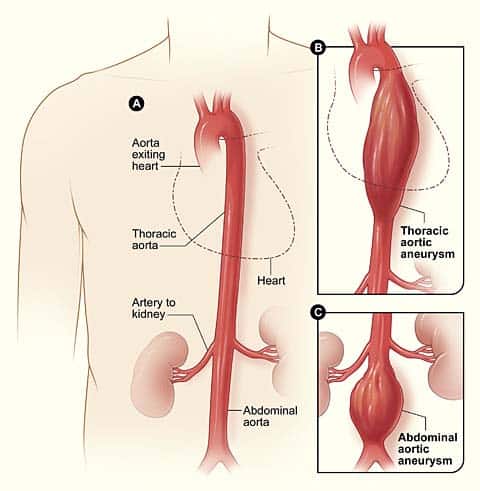

Clinical Relevance: Aortic Aneurysm

Aortic aneurysm describes a dilation of the artery to more than 1.5 times its original size. The abdominal component of the aorta is the most common site for aneurysmal changes.

Patients suffering with an abdominal aortic aneurysm may experience abdominal pulsations, abdominal pain and back pain. The aneurysm may also compress nerve roots causing pain/numbness in the lower limbs. A patient with an aortic arch aneurysm may have a hoarse voice due to the dilation stretching the left recurrent laryngeal nerve. Patients may also not have any symptoms at all.

Small aortic aneurysms do not usually pose a serious immediate threat. Diagnosis is made from an ultrasound and the weakened vessel wall can be surgically replaced with a piece of synthetic tubing. If left untreated, a large aneurysm can rupture. This is a medical emergency and often fatal.

Fig 6 – Aortic aneurysm, a dilation of the vessel more than 1.5 times the original diameter.

![Fig 1.0 - Overview of the anatomical course of the aorta. By Edoarado [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons](https://teachmeanatomy.info/wp-content/uploads/Overview-of-the-anatomical-course-of-the-aorta.jpg)