The tongue is a muscular structure located on the floor of the oral cavity.

It is the primary taste organ and plays a key role in the initial phases of swallowing.

In this article, we shall look at the anatomy of the tongue – its structure, innervation and clinical correlations.

Intrinsic Muscles

The intrinsic muscles originate and attach to other structures within the tongue.

There are four paired intrinsic muscles of the tongue and they are named by the direction in which they travel – the superior longitudinal, inferior longitudinal, transverse and vertical muscles of the tongue. These muscles affect the shape and size of the tongue – for example, in tongue rolling – and have a role in facilitating speech, eating and swallowing.

The motor innervation to the intrinsic muscles of the tongue is via the hypoglossal nerve (CN XII).

Extrinsic Muscles

The extrinsic muscles of the tongue originate from structures outside the tongue and insert onto it.

They are innervated by the hypoglossal nerve – with the exception of the palatoglossus, which is innervated by the vagus nerve.

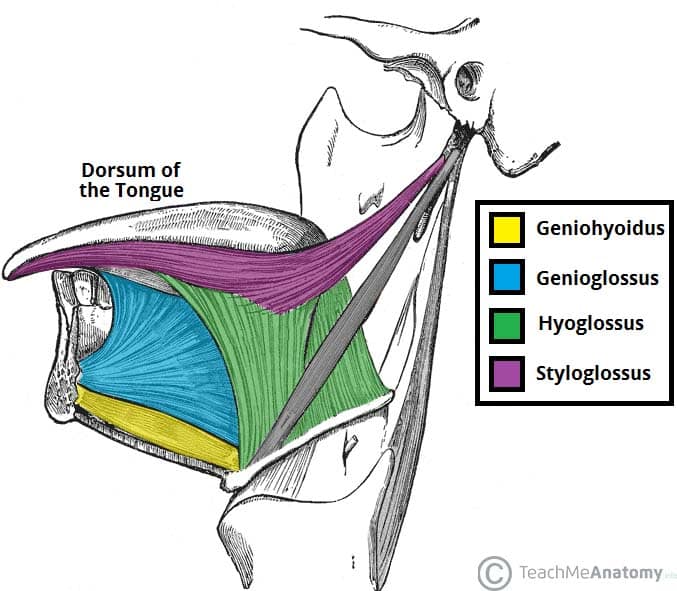

Genioglossus

The genioglossus muscle is a large, thick muscle, which contributes significantly to the shape of the tongue.

- Attachments: Arises from the mandibular symphysis. It inserts onto the body of the hyoid bone and the entire length of the tongue.

- Function: Protrusion (‘sticking the tongue out’) and depression of the tongue.

- Innervation: Hypoglossal nerve.

Hyoglossus

The hyoglossus muscle is located in the floor of the oral cavity, immediately lateral to the geniohyoid.

- Attachments: Arises from the hyoid bone and inserts onto the lateral aspect of the tongue.

- Function: Depression and retraction of the tongue.

- Innervation: Hypoglossal nerve.

Styloglossus

The styloglossus is a thin, paired muscle, located on either side of the oropharynx.

- Attachments: Originates from the styloid process of the temporal bone and inserts onto the lateral aspect of the tongue.

- Function: Retraction and elevation of the tongue.

- Innervation: Hypoglossal nerve.

Palatoglossus

The palatoglossus muscle is also associated with the soft palate – and is therefore innervated by the vagus nerve.

- Attachments: Arises from the palatine aponeurosis and inserts broadly along the tongue.

- Function: Elevation of the posterior tongue

- Innervation: Vagus nerve.

Fig 1 – The extrinsic muscles of the tongue. Note the palatoglossus muscle is not included in this illustration.

Innervation

Once we start examining the sensory supply of the tongue, we need to start looking at its division into an anterior 2/3, and a posterior 1/3. Later in this article, when we discuss the development of the tongue, the reason for this boundary becomes clear.

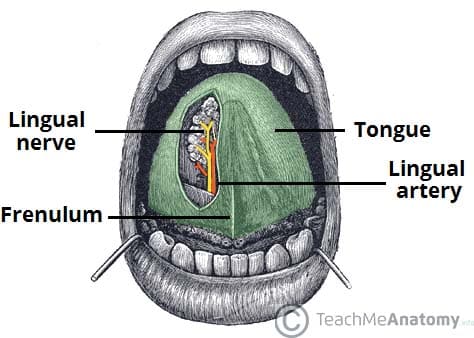

In the anterior 2/3, general sensation is supplied by the trigeminal nerve (CNV). Specifically the lingual nerve, a branch of the mandibular nerve (CN V3).

On the other hand, taste in the anterior 2/3 is supplied from the facial nerve (CNVII). In the petrous part of the temporal bone, the facial nerve gives off three branches, one of which is chorda tympani. This travels through the middle ear, and continues on to the tongue.

The posterior 1/3 of the tongue is slightly easier. Both touch and taste are supplied by the glossopharyngeal nerve (CNIX).

Fig 2 – The lingual nerve provides sensory innervation to the to the 2/3 of the tongue.

Vasculature

The arterial supply to the tongue is mainly from the lingual artery (a branch of the external carotid artery). There are also contributions from the tonsillar branch of the facial artery.

Venous drainage is by the lingual vein – which empties into the internal jugular vein.

Lymphatic Drainage

The lymphatic drainage of the tongue is as follows:

- Anterior two thirds – initially into the submental and submandibular nodes, which empty into the deep cervical lymph nodes

- Posterior third – directly into the deep cervical lymph nodes

Embryological Development

A good understanding of the tongue’s embryological development greatly simplifies the complex innervation to the structure. One of the central points is that the first branchial arch is supplied by the trigeminal nerve, the second by the facial, the third by the glossopharyngeal, and the fourth and sixth by the vagus.

When the tongue is developing, it starts as a two longitudinal bulbous ridges, with contribution from the first four branchial arches. These ridges join, giving rise to the longitudinal line (median sulcus) down the centre of your tongue. The contribution from the second branchial arch is grown over by that of the third arch, but the nerve supply remains. Using this information, we can understand why the majority of the tongue’s innervation is by the trigeminal nerve (CN V) and the glossopharyngeal nerve CN IX.

Look further towards the back of your tongue – there is a transverse line near the root of the tongue. This is called sulcus terminalis, and in the centre, where it meets the median sulcus, there is a pit. This is the now-closed top of a deep pit, the foramen cecum (blind window), at the end of which lies the thyroid gland. During development, this descends from the tongue down into the neck, If, on the way down, the pit (thyroglossal duct) doesn’t close behind the gland, midline thyroglossal cysts or fistulae may remain.

Clinical Relevance – Tongue-Tie

The tongue is attached anteroinferiorly by a piece of connective tissue called the frenulum, which lies in the midline. The process by which the frenulum is formed is the same by which your fingers are made, and is known as sculpting apoptosis.

Just as some people may have webbed fingers if this process fails, it can result in excess frenulum. This is called being ‘tongue-tied’, and presents in children.

There are varying degrees of severity of tongue-tie and in some cases it can restrict the movement of the tongue causing difficulties with breast feeding. It can be managed with simple surgery.