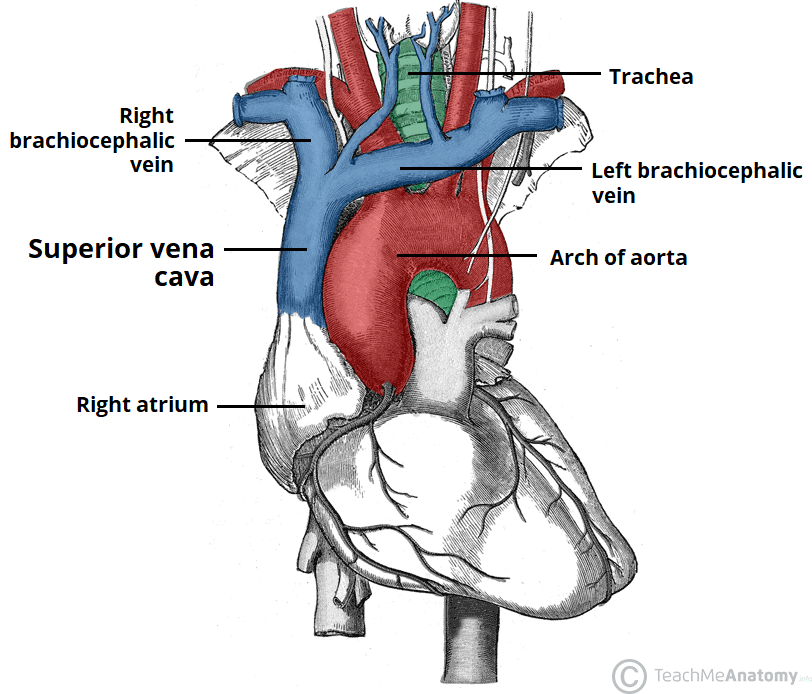

The superior vena cava (SVC) is a large, valveless vein that conveys venous blood from the upper half of the body and returns it to the right atrium.

In this article, we will look at the anatomy of the superior vena cava – its position, tributaries, and clinical correlations.

Anatomical Position

The superior vena cava is classified as a large vein, with a wide diameter of up to 2cm and a length of approximately 7cm.

It arises from the union of the left and right brachiocephalic veins, posterior to the first right costal cartilage. It descends vertically through the superior mediastinum, behind the intercostal spaces and to the right of the aorta and trachea.

At the level of the second costal cartilage, the SVC enters the middle mediastinum and becomes surrounded by the fibrous pericardium. It terminates by emptying into the superior aspect of the right atrium at the level of the third costal cartilage.

Clinical Relevance: Jugular Venous Pressure

The superior vena cava is a valveless structure. This allows the pressure in the right atrium to be conducted upwards into the right internal jugular vein.

Visualisation of the right internal jugular vein is an indicator of the jugular venous pressure – which in turn represents the pressure in the right atrium. To examine, the patient should be at a 45° angle with their head turned slightly to the left. The JVP can be identified as a pulsation between the two heads of the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

Causes of a raised JVP include right-sided heart failure, pulmonary hypertension, and SVC obstruction.

Tributaries

The superior vena cava contains venous blood from the head, neck, both upper limbs and from structures within the thorax

It is formed by the union of the right and left brachiocephalic veins – which provide venous drainage of the head, neck, and upper limbs. At the level of T4, the superior vena cava receives the azygous vein, which drains the upper lumbar region and thoracic wall.

The SVC receives tributaries from several minor vein groups:

- Mediastinal veins

- Oesophageal veins

- Pericardial veins

Clinical Relevance: Superior Vena Cava Obstruction

The superior vena cava is a thin-walled, low pressure vessel which makes it vulnerable to compression.

Superior vena cava obstruction can occur either due to external compression or from an occlusion within the vessel lumen itself. The most common cause of SVC obstruction is malignancy, typically from lung cancer, lymphoma, or metastatic disease.

Vessel obstruction interrupts venous return and can lead to swelling in the neck, face, and upper limbs. Clinical features include shortness of breath and distension of the veins of the face and upper limb.

SVC obstruction can be assessed clinically by performing Pemberton’s test. The patient is asked to raise both arms above their head – a positive test is indicated if facial oedema or cyanosis occurs after approximately 1 minute.