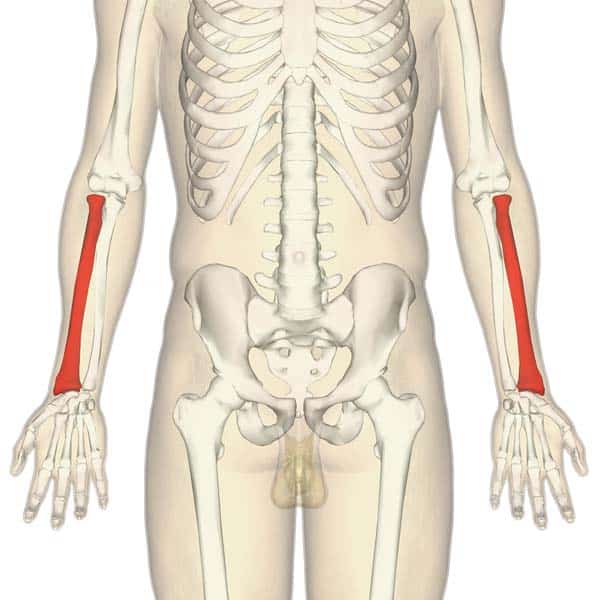

Fig 1.0 – The anatomical position of the radius.

The radius is a long bone in the forearm. It lies laterally and parallel to ulna, the second of the forearm bones. The radius pivots around the ulna to produce movement at the proximal and distal radio-ulnar joints.

The radius articulates in four places:

- Elbow joint – Partly formed by an articulation between the head of the radius, and the capitulum of the humerus.

- Proximal radioulnar joint – An articulation between the radial head, and the radial notch of the ulna.

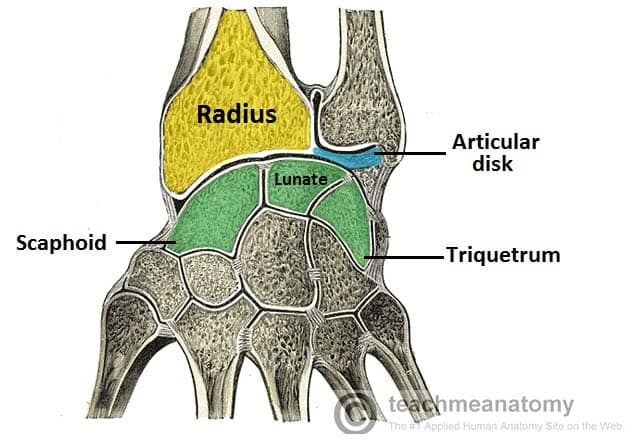

- Wrist joint – An articulation between the distal end of the radius and the carpal bones.

- Distal radioulnar joint – An articulation between the ulnar notch and the head of the ulna.

In this article, we shall look at the bony landmarks and osteological features of the radius.

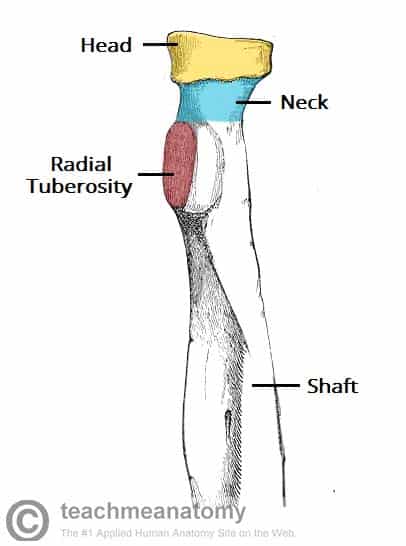

Proximal End

The proximal end of the radius articulates in both the elbow and proximal radioulnar joints.

Important bony landmarks include the head, neck and radial tuberosity:

- Head of radius – A disk shaped structure, with a concave articulating surface. It is thicker medially, where it takes part in the proximal radioulnar joint.

- Neck – A narrow area of bone, which lies between the radial head and radial tuberosity.

- Radial tuberosity – A bony projection, which serves as the place of attachment of the biceps brachii muscle.

Shaft

The radial shaft expands in diameter as it moves distally. Much like the ulna, it is triangular in shape, with three borders and three surfaces.

In the middle of the lateral surface, there is a small roughening for the attachment of the pronator teres muscle.

Distal End

In the distal region, the radial shaft expands to form a rectangular end. The lateral side projects distally as the styloid process. In the medial surface, there is a concavity, called the ulnar notch, which articulates with the head of ulna, forming the distal radioulnar joint.

The distal surface of the radius has two facets, for articulation with the scaphoid and lunate carpal bones. This makes up the wrist joint.

Clinical Relevance: Common Fractures of the Radius

The forearm is a common site for bone fractures. Here, we shall look at the common fracture types involving the radius:

- Colles’ fracture – The most common type of radial fracture. A fall onto an outstretched hand causing a fracture of the distal radius. The structures distal to the fracture (wrist and hand) are displaced posteriorly. It produces what is known as the ‘dinner fork deformity’.

- Fractures of the radial head – This is characteristically due to falling on an outstretched hand. The radial head is forced into the capitulum of humerus, causing it to fracture.

- Smith’s fracture – A fracture caused by falling onto the back of the hand. It is the opposite of a Colles’ fracture, as the distal fragment is displaced anteriorly.

Fig 1.3 – Colles’ fracture of the wrist. Note the ‘dinner fork’ deformity, produced by the posterior displacement of the radius.

The radius and the ulna are attached by the interosseous membrane. The force of a trauma to one bone can be transmitted to the other via this membrane. Thus, fractures of both the forearm bones are not uncommon.

There are two classical fractures:

- Monteggia – usually caused by a force from behind the ulna. The proximal shaft of ulna is fractured, and the head of the radius dislocates anteriorly at the elbow.

- Galeazzi – a fracture to the distal radius, with the ulna head dislocating at the distal radio-ulnar joint.