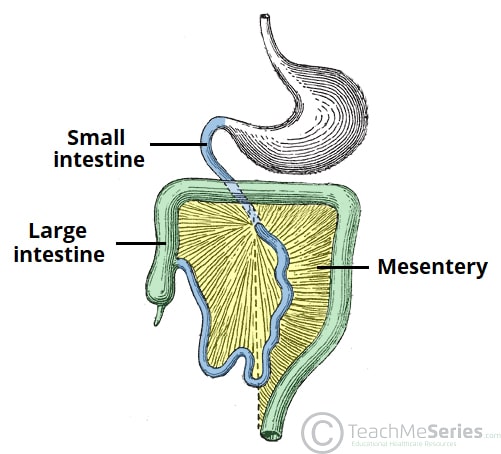

The mesentery is a double fold of peritoneal tissue that suspends the small intestine and large intestine from the posterior abdominal wall.

It was previously thought to be a collection of discrete structures – each with separate insertions into the posterior wall. However, recent research has found the mesentery to be one contiguous structure, which has led to proposals for its reclassification as an organ.

In this article, we shall look at the anatomy of the mesentery – its anatomical structure, vasculature, innervation, lymphatics and clinical relevance.

Note: Research regarding the mesentery is relatively recent, and some older textbooks may still describe the different parts of the mesentery as separate structures – this is now thought to be incorrect.

Fig 1 – Simplified illustration of the mesentery. It acts to connect the small intestine and large intestine to the posterior abdominal wall.

Function

The mesentery has several functions in the abdomen:

- Suspends the small and large intestine from the posterior abdominal wall; anchoring them in place, whilst still allowing some movement.

- Provides a conduit for blood vessels, nerves and lymphatic vessels.

- Postulated to play a pathological role in inflammatory diseases such as Crohn’s disease.

Structure

The mesentery is formed by a double layered fold of peritoneum.

Although the mesentery is now thought to be a contiguous structure, subsections of the mesentery can be named according to the viscera it is associated with. Thus, names such as mesocolon, mesorectum, mesosigmoid all relate to different parts of the mesentery.

The ‘root’ of the mesentery is the point where the mesentery attaches to the posterior abdominal wall, and is therefore a ‘bare area’. Due to the range of abdominal organs the mesentery envelopes, the root is long, narrow and has an oblique orientation, from the left side of the L2 vertebra to the right sacroiliac junction roughly.

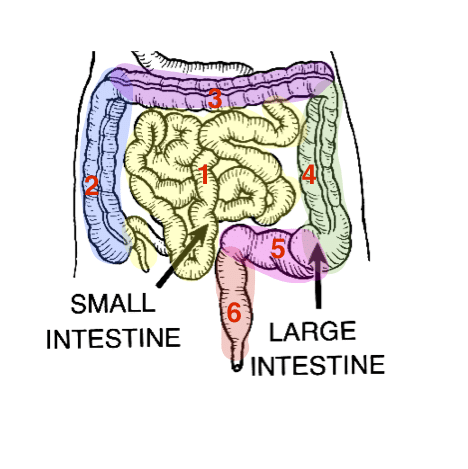

In the gastrointestinal tract, there are six flexures of note: duodenojejunal, ileocaecal, hepatic, splenic, and those between the descending and sigmoid colon and the sigmoid and rectum. These flexures are often used to mark the distinction between different portions of the mesentery:

- Mesentery of the small intestine – connects the loops of jejunum and ileum to the posterior abdominal wall and is a mobile structure. (1)

- Right mesocolon – flattened against the posterior abdominal wall (2)

- Transverse mesocolon – a mobile structure and lies between the colic flexures (3)

- Left mesocolon – flattened against the posterior abdominal wall (4)

- Mesosigmoid – has a medial portion which is flattened against the posterior abdominal wall, whereas the region of mesentery associated with the sigmoid colon itself is mobile. (5)

- Mesorectum – assists in anchoring the rectum through the pelvis.(6)

Fig 2 – Small intestine and and large intestine highlighted to show associated mesentery.

The areas of the mesentery that are flattened against the posterior abdominal wall (the right and left mesocolon and the medial mesosigmoid) are attached to the abdominal wall via an additional layer of connective tissue known as Toldt’s fascia. The fascia contains several lymphatic channels.

Clinical Relevance: Intestinal Volvulus

A volvulus occurs when a loop of intestine twists around itself and its mesentery, causing obstruction of the bowel. It is possible that the bowel will twist tightly enough to prevent the blood supply to the intestine, and result in bowel infarction.

The most commonly affected area of bowel is the sigmoid colon. The risk of intestinal volvulus is increased in children with intestinal malrotation, a congenital defect in which the embryological intestinal rotation is incomplete, resulting in improper anchoring of the intestines to the posterior abdominal wall.

Medical imaging (abdominal x-ray, CT abdo-pelvis) is frequently used to confirm a diagnosis, and serious cases require surgical intervention.

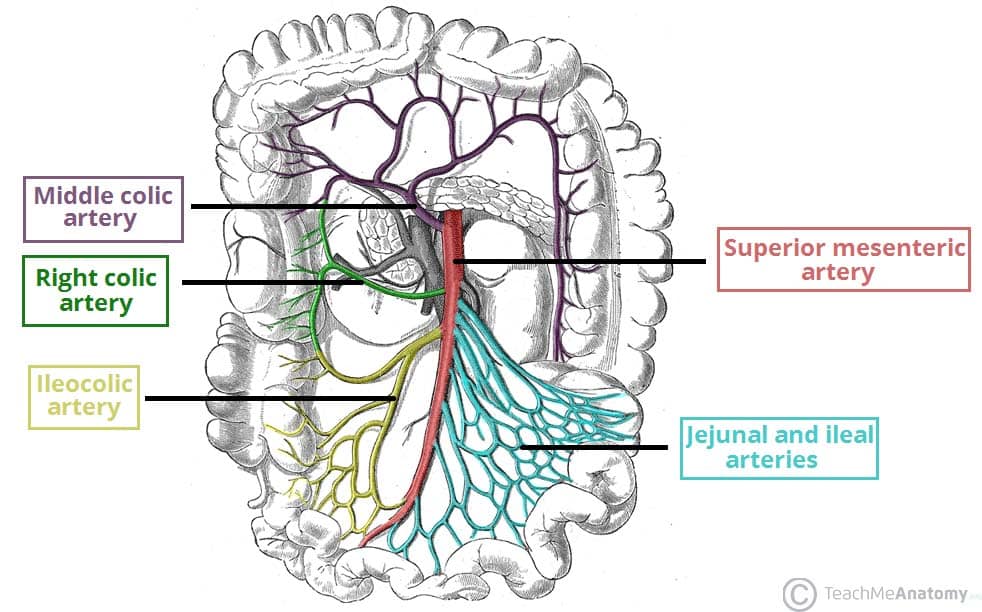

Vasculature

The mesentery acts a conduit for neurovascular structures.

The superior and inferior mesenteric arteries (SMA and IMA) arise from the abdominal aorta and travel in the mesentery to supply the abdominal viscera. These vessels also give rise to branches that supply the mesentery itself.

- Superior mesenteric artery – supplies the organs of the midgut – from the major duodenal papilla to the proximal two thirds of the transverse colon.

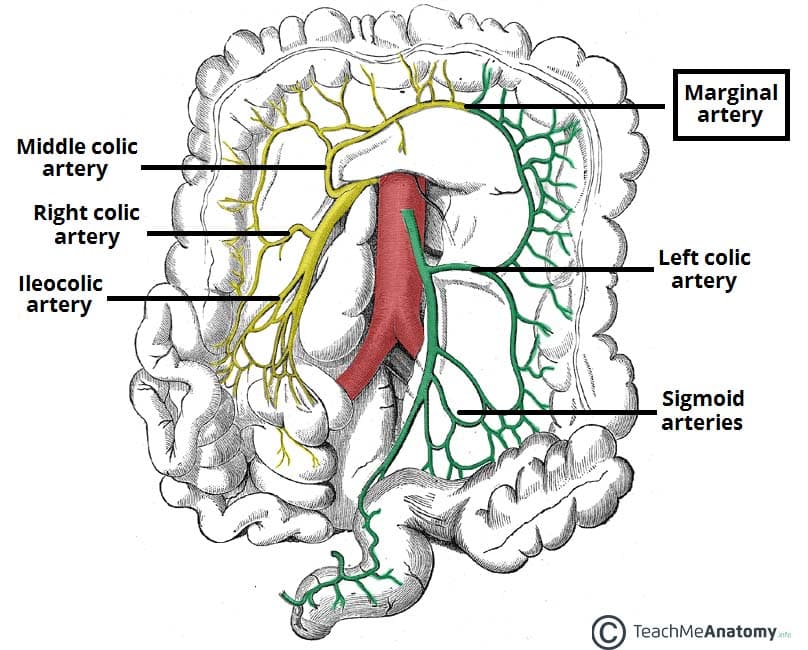

- Inferior mesenteric artery – supplies the organs of the hindgut – the distal one third of the transverse colon, splenic flexure, descending colon, sigmoid colon and rectum.

The venous drainage of the mesentery is via the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) and inferior mesenteric vein (IMV), which both run alongside their associated arteries.

Fig 4 – The superior mesenteric artery and its branches. Note: the inferior pancreatoduodenal artery arises more proximally, and is not visible on this illustration.

Fig 5 – Major branches of the inferior mesenteric artery demonstrated in green

Innervation

The superior mesenteric plexus (a continuation of the celiac plexus) accompanies the superior mesenteric artery into the mesentery.

The superior mesenteric plexus then divides into many secondary plexuses which contain parasympathetic and sympathetic innervation to the mesentery associated with a particular organ, the organs themselves and their related blood vessels.

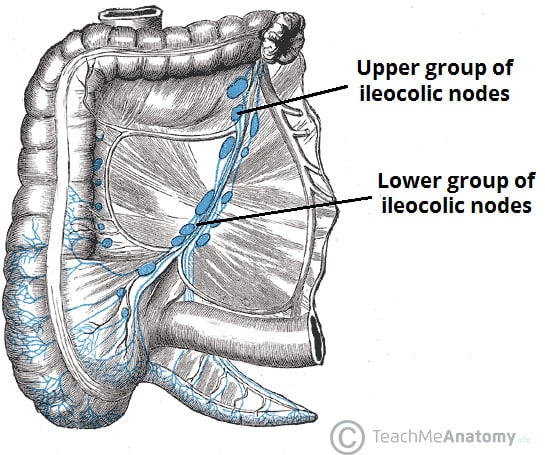

Lymphatics

The mesentery contains both lymph nodes and lymphatic vessels. There are several groups of lymph nodes found within the mesentery:

- Inferior mesenteric lymph nodes – receives lymph from the hindgut organs, and drains into the superior mesenteric lymph nodes.

- Superior mesenteric lymph nodes – receives lymph from the midgut organs (and from the inferior mesenteric nodes), and drains into the pre-aortic lymph nodes.