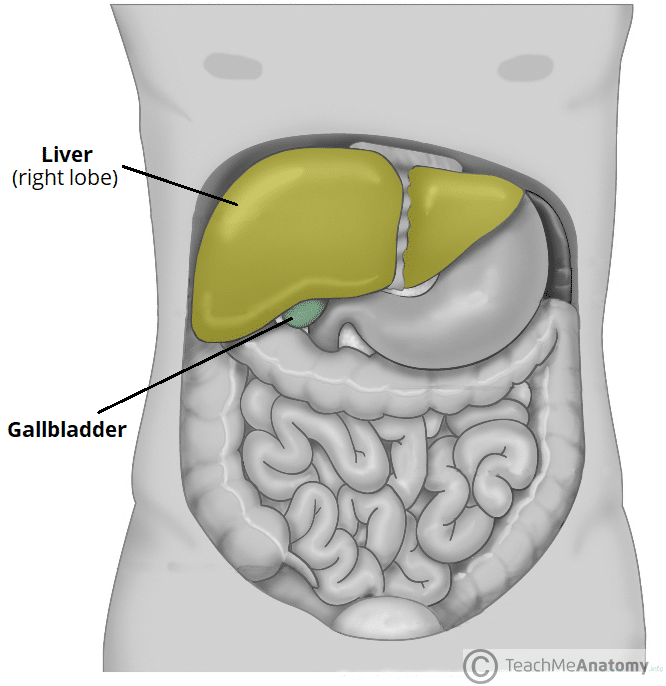

The gallbladder is a gastrointestinal organ located within the right hypochondrial region of the abdomen. This intraperitoneal, pear-shaped sac lies within a fossa formed between the inferior aspects of the right and quadrate lobes of the liver.

The primary function of the gallbladder is to concentrate and store bile which is produced by the liver. As part of the gustatory response, the stored bile is then released from the gallbladder in response to cholecystokinin.

In this article, we shall look at the anatomy of the gallbladder – its structure, vasculature, innervation and lymphatic supply.

Anatomical Relations

The gallbladder is entirely surrounded by peritoneum, and is in direct relation to the visceral surface of the liver.

It lies in close proximity to the following structures:

- Anteriorly and superiorly – inferior border of the liver and the anterior abdominal wall.

- Posteriorly – transverse colon and the proximal duodenum.

- Inferiorly – biliary tree and remaining parts of the duodenum.

Fig 1 – The gallbladder is related to the inferior surface of the liver.

Anatomical Structure

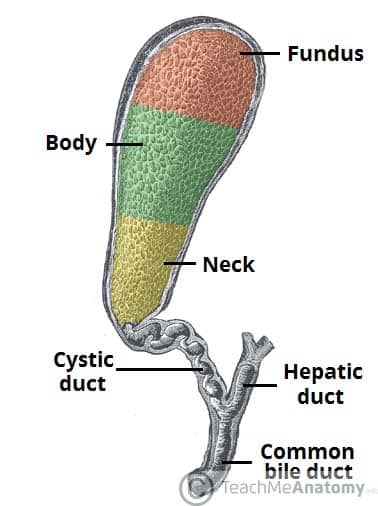

The gallbladder has a storage capacity of 30-50ml and, in life, lies anterior to the first part of the duodenum. It is typically divided into three parts:

- Fundus – the rounded, distal portion of the gallbladder. It projects into the inferior surface of the liver in the mid-clavicular line.

- Body – the largest part of the gallbladder. It lies adjacent to the posteroinferior aspect of the liver, transverse colon and superior part of the duodenum.

- Neck – the gallbladder tapers to become continuous with the cystic duct, leading into the biliary tree.

- The neck contains a mucosal fold, known as Hartmann’s Pouch. This is a common location for gallstones to become lodged, causing cholestasis.

The Biliary Tree

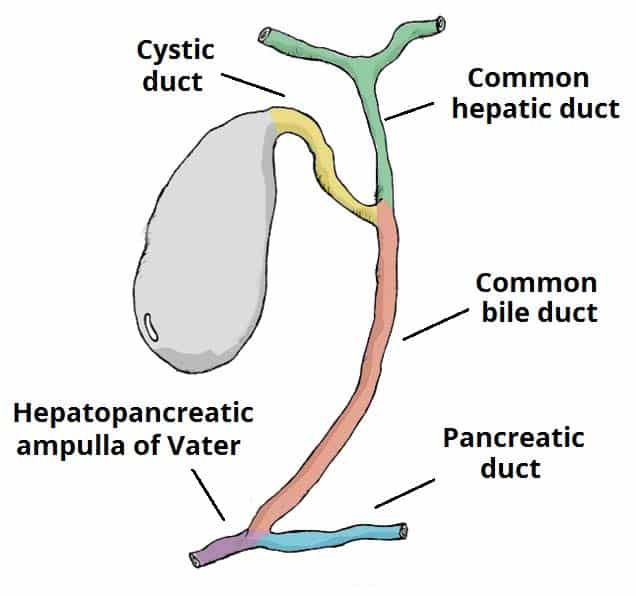

The biliary tree is a series of gastrointestinal ducts allowing newly synthesised bile from the liver to be concentrated and stored in the gallbladder (prior to release into the duodenum).

Bile is initially secreted from hepatocytes and drains from both lobes of the liver via canaliculi, intralobular ducts and collecting ducts into the left and right hepatic ducts. These ducts amalgamate to form the common hepatic duct, which runs alongside the hepatic vein.

As the common hepatic duct descends, it is joined by the cystic duct – which allows bile to flow in and out of the gallbladder for storage and release. At this point, the common hepatic duct and cystic duct combine to form the common bile duct.

The common bile duct descends and passes posteriorly to the first part of the duodenum and head of the pancreas. Here, it is joined by the main pancreatic duct, forming the hepatopancreatic ampulla (commonly known as the ampulla of Vater) – which then empties into the duodenum via the major duodenal papilla. This papilla is regulated by a muscular valve, the sphincter of Oddi.

Vasculature

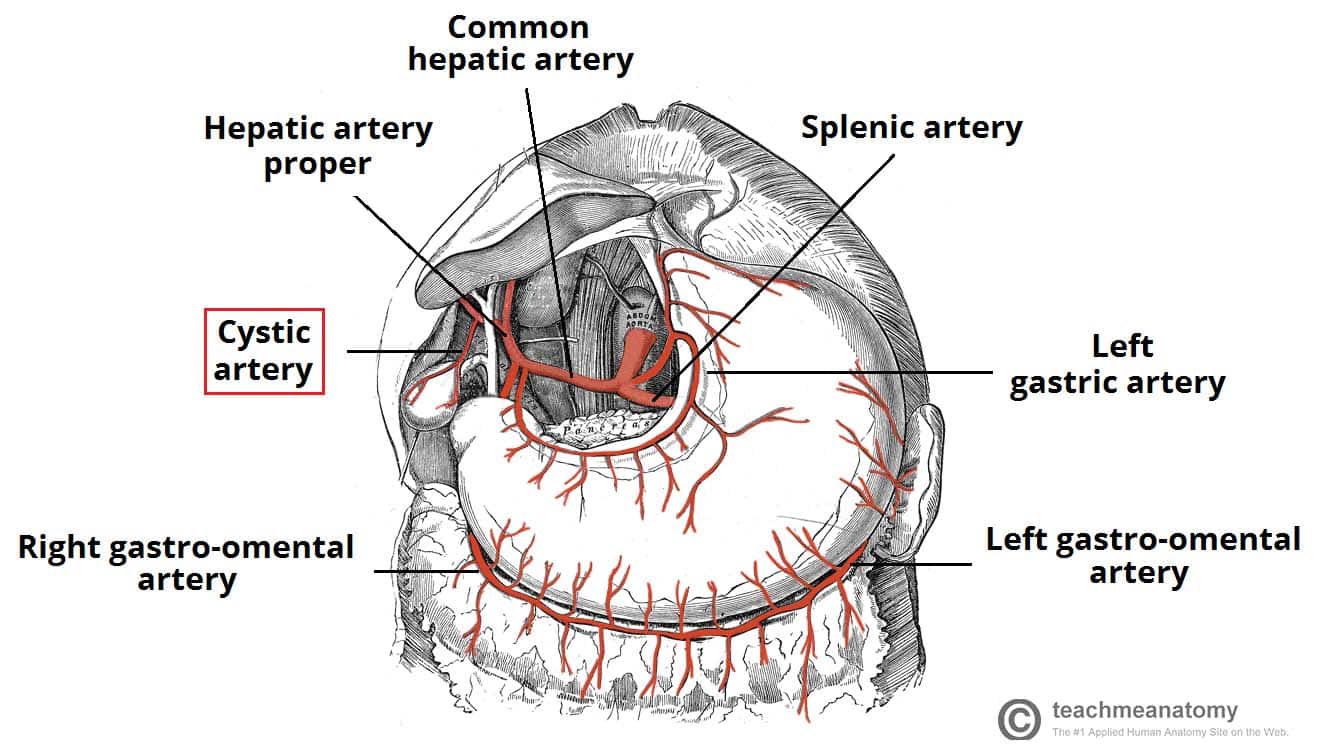

The arterial supply to the gallbladder is via the cystic artery – a branch of the right hepatic artery (which itself is derived from the common hepatic artery, one of the three major branches of the coeliac trunk).

Venous drainage of the neck of the gallbladder is via the cystic veins, which drain directly into the portal vein. Venous drainage of the fundus and body of the gallbladder flows into the hepatic sinusoids.

Innervation

The gallbladder receives parasympathetic, sympathetic and sensory innervation.

The coeliac plexus carries sympathetic and sensory fibres, while the vagus nerve delivers parasympathetic innervation.

Parasympathetic stimulation produces contraction of the gallbladder, and the secretion of bile into the cystic duct due to relaxation of the sphincter of Oddi. The majority of this response however, is mediated by circulating cholecystokinin as part of the gustatory response.

Lymph Drainage

Lymph from the gallbladder drains into the cystic lymph nodes, situated at the gallbladder neck.

The cystic nodes then empty into the hepatic lymph nodes, and ultimately, the coeliac lymph nodes.

Clinical Relevance: Gallstones

Cholelithiasis, commonly known as gallstones, are small lumps of cholesterol, bile salts or a mixture of the two, which may form within the gallbladder. They are relatively common and often asymptomatic.

However, they may be associated with pain, jaundice and systemic upset (depending on the location of the gallstone, and the presence or absence of associated infection or inflammation).

Different terminologies are applied to distinguish between these pathologies:

- Cholelithiasis – uncomplicated gallstones

- Biliary colic – typically right upper quadrant pain following a fatty meal as gallstones obstruct the cystic duct during contraction of the gallbladder. Not associated with systemic upset

- Cholecystitis – inflammation of the gallbladder. Pain is often associated with nausea, vomiting or fever

- Choledocholithiasis – gallstone within the common bile duct. Often causes deranged liver function tests.

- Cholangitis – infection of the common bile duct often secondary to choledocholithiasis. Typically presents with right upper quadrant pain, fever and jaundice (Charcot’s Triad)

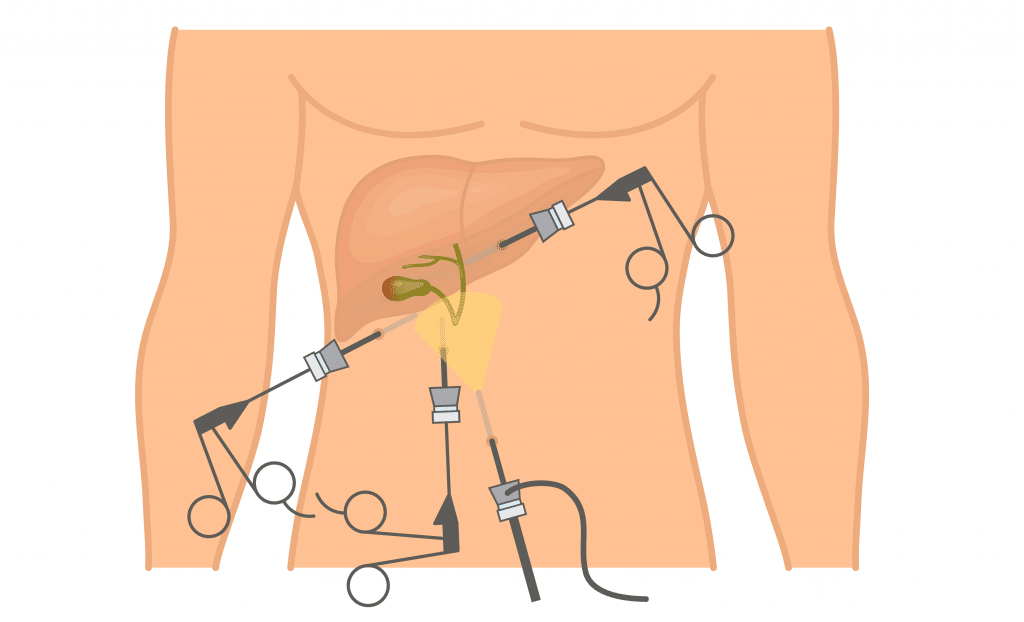

Once diagnosed, most symptomatic patients have surgical removal of the gallbladder (cholecystectomy); which is now often performed via laparoscopic (key-hole) surgery during the acute phase or once recovery has taken place (often at 6 weeks). In the interim, patients are prescribed analgesia and antibiotics when required.