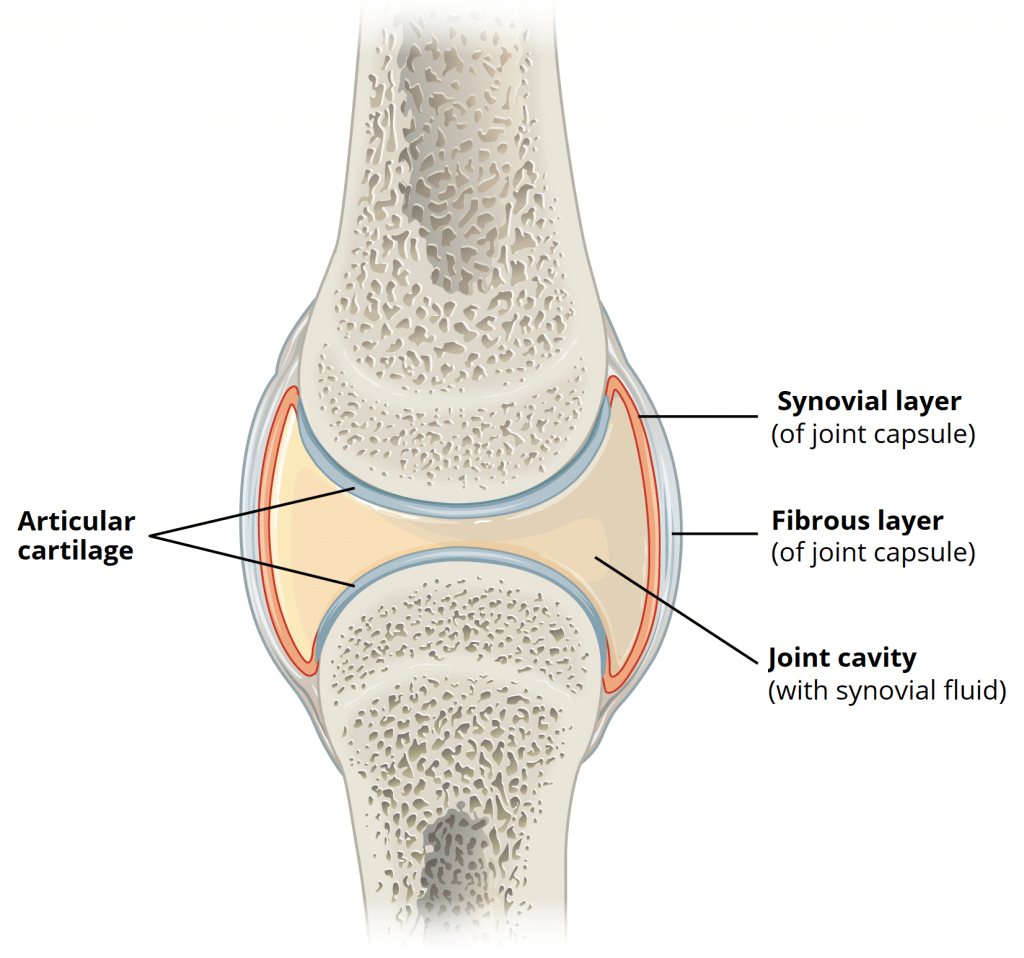

A synovial joint is characterised by the presence of a fluid-filled joint cavity contained within a fibrous capsule.

It is the most common type of joint found in the human body, and contains several structures which are not seen in fibrous or cartilaginous joints.

In this article we shall look at the anatomy of a synovial joint – the joint capsule, neurovascular structures and clinical correlations.

Key Structures of a Synovial Joint

The three main features of a synovial joint are: (i) articular capsule, (ii) articular cartilage, (iii) synovial fluid.

Articular Capsule

The articular capsule surrounds the joint and is continuous with the periosteum of articulating bones.

It consists of two layers:

- Fibrous layer (outer) – consists of white fibrous tissue, known the capsular ligament. It holds together the articulating bones and supports the underlying synovium.

- Synovial layer (inner) – a highly vascularised layer of serous connective tissue. It absorbs and secretes synovial fluid, and is responsible for the mediation of nutrient exchange between blood and joint. Also known as the synovium.

Fig 1 – The basic structures of a synovial joint.

Articular Cartilage

The articulating surfaces of a synovial joint (i.e. the surfaces that directly contact each other as the bones move) are covered by a thin layer of hyaline cartilage.

The articular cartilage has two main roles: (i) minimising friction upon joint movement, and (ii) absorbing shock.

Synovial Fluid

The synovial fluid is located within the joint cavity of a synovial joint. It has three primary functions:

- Lubrication

- Nutrient distribution

- Shock absorption.

Articular cartilage is relatively avascular, and is reliant upon the passive diffusion of nutrients from the synovial fluid.

Accessory Structures of a Synovial Joint

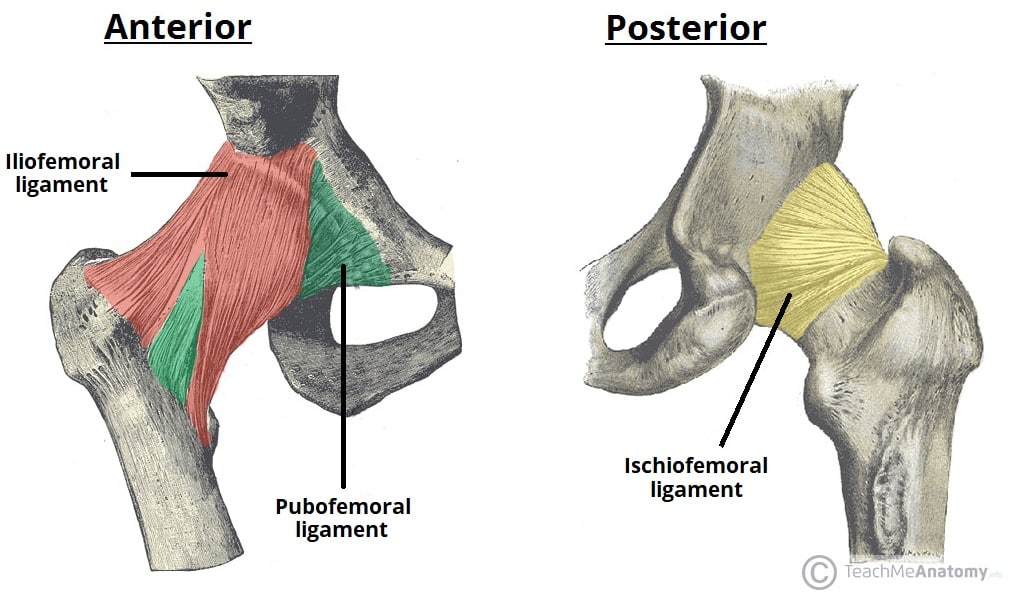

Accessory Ligaments

The accessory ligaments are separate ligaments or parts of the joint capsule.

They consist of bundles of dense regular connective tissue, which is highly adapted for resisting strain. This resists any extreme movements that may damage the joint.

Fig 2 – The extracapsular ligaments of the hip joint; ileofemoral, pubofemoral and ischiofemoral ligaments.

Bursae

A bursa is a small sac lined by synovial membrane, and filled with synovial fluid.

Bursae are located at key points of friction in a joint. They afford joints greater freedom of movement, whilst protecting the articular surfaces from friction-induced degeneration

They can become inflamed following infection or irritation by over-use of the joint (bursitis).

Innervation

Synovial joints have a rich supply from articular nerves.

The innervation of a joint can be determined using Hilton’s Law – ‘the nerves supplying a joint also supply the muscles moving the joint and the skin covering their distal attachments.’

Articular nerves transmit afferent impulses, including proprioceptive (joint position) and nociceptive (pain) sensation

Vasculature

Arterial supply to synovial joints is via articular arteries, which arise from the vessels around the joint. The articular arteries are located within the joint capsule, mostly in the synovial membrane.

A common feature of the articular arterial supply is frequent anastomoses (communications) in order to ensure a blood supply to and across the joint regardless of its position. In practice this usually means arteries are above and below a joint, curving round each side of it and joining via small connecting vessels.

The articular veins accompany the articular arteries and are also found in the synovial membrane.

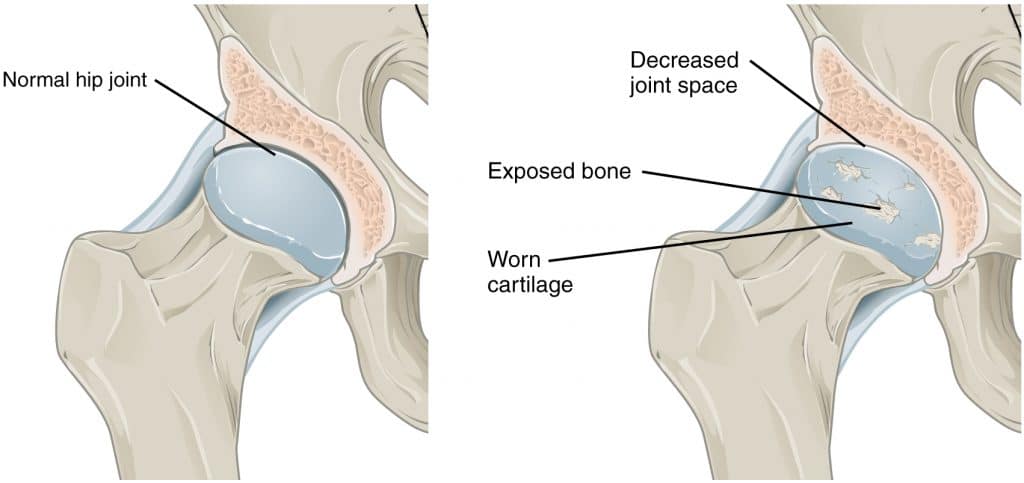

Clinical Relevance: Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis is the most common form of joint inflammation (arthritis). It stems from heavy use of articular joints over the course of many years, which can result in the wearing away of articular cartilage, and often the erosion of the underlying articulating surfaces of bones as well.

The changes which occur are irreversible and degenerative. This results in the decreased effectiveness of articular cartilage as a shock absorber and lubricated surface, as well as the roughened edges causing further damage.

As a result of this degeneration, repeated friction can cause symptoms of joint pain, stiffness and discomfort. This condition usually affects joints that support full body weight, such as the hips and the knees.

Arthritis can also come about through other causes, including; (i) as a result of infection, due to the ease with which blood (and any associated bacteria) can enter the joint cavity via the synovial membrane; (ii) due to autoinflammatory causes, as in rheumatoid arthritis, or; (iii) as a result of infection but not involving infection of the joint itself, as in reactive arthritis.