Teeth are organised into two opposing arches – maxillary (upper) and mandibular (lower). These can be divided down the midline (mid-sagittal plane) into left and right halves. Teeth are positioned in alveolar sockets, and connected to the bone by a suspensory periodontal ligament.

In this article, we shall look at the development of the teeth – their precursor tissues, differentiation, and related clinical conditions.

Embryological Development

Teeth develop and erupt at different times as a result of a complex, multi-step process, involving the patterning of inductive signals and homeobox genes. Signalling occurs between the oral epithelium and the underlying mesenchyme. Temporal and spatial control of gene expression leads to formation of different tooth types.

Tooth development is recognised to occur in stages – initiation, morphogenesis, and differentiation.

Initiation

Tooth initiation begins at the 6th week in utero, when ectomesenchymal cells accumulate immediately below the oral epithelium. These cells are thought be derived from the neural crest cell population.

The oral epithelium then proliferates down into the ectomesenchyme to form a primary epithelial band.

At the 7th week in utero, the primary epithelial band differentiates into the vestibular and dental laminae:

- Vestibular lamina – forms the oral vestibule (the external opening to the oral cavity)

- Dental lamina – forms the teeth

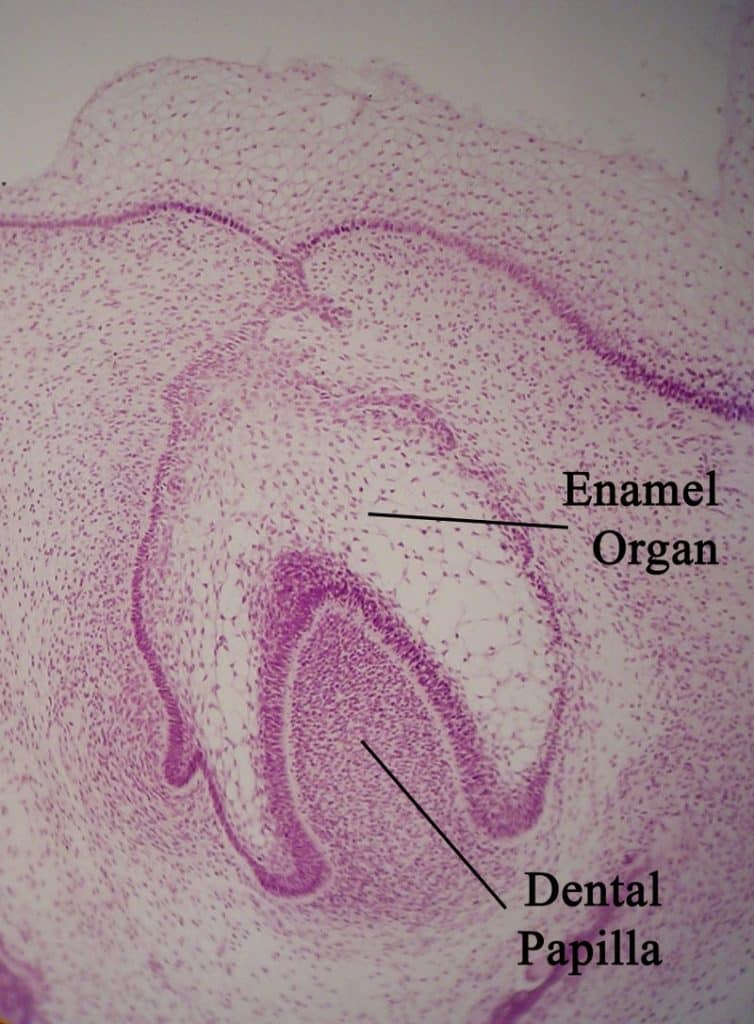

Within the dental lamina, epithelial swellings form – these are known as the dental buds, of which there are 10 in each jaw. They give rise to the enamel organs (precursor to tooth enamel), signalling the first stages of individual tooth type development.

Beneath the enamel organs, ectomesenchymal tissue condenses to form the dental papilla (precursor to dentin and pulp).

Morphogenesis

Morphogenesis commences at the 10th week in utero, when five developing tooth germs appear in each quadrant, which give rise to the primary dentition.

By the 16th week in utero, the tooth germs of the permanent incisors and the 1st permanent molars begin to form. The 2nd and 3rd permanent molar tooth germs appear long after birth.

Differentiation

By the 18th week in utero, differentiation of tooth germs has occurred and dental hard tissue has formed. Alveolar bone forms around the developing dental follicle.

Later Development

The process of tooth development continues for a period in excess of 10 years, whereas the process of tooth eruption continues for almost 20 years.

Developmental disturbances that occur at any time during the period of tooth formation, may result in anomalies of tooth number, size, shape or structure.

Clinical Relevance: Hypodontia and Hyperdontia

Hypodontia is a condition in which fewer teeth form than is expected. Teeth that most commonly fail to form are the 3rd molars, the second premolars, and the lateral incisors. Ectodermal dysplasia is a condition in which multiple teeth are developmentally absent.

Hyperdontia is where supernumerary, or supplemental, teeth are formed, in addition to the normal expected series. These teeth often have an unusual morphology. They may erupt, or may remain unerupted. They may prevent eruption of teeth in the normal series. Cleidocranial dysplasia is a condition in which multiple supernumerary teeth form.