The eyeball is a bilateral and spherical organ, which houses the structures responsible for vision. It lies in a bony cavity within the facial skeleton – known as the bony orbit.

Anatomically, the eyeball can be divided into three parts – the fibrous, vascular and inner layers. In this article, we shall consider the anatomy of the eyeball in detail, and its clinical correlations.

Layers of the Eyeball

The eyeball is formed by three layers – fibrous, vascular and inner. Each of these layers has a specialised structure and function.

Fibrous

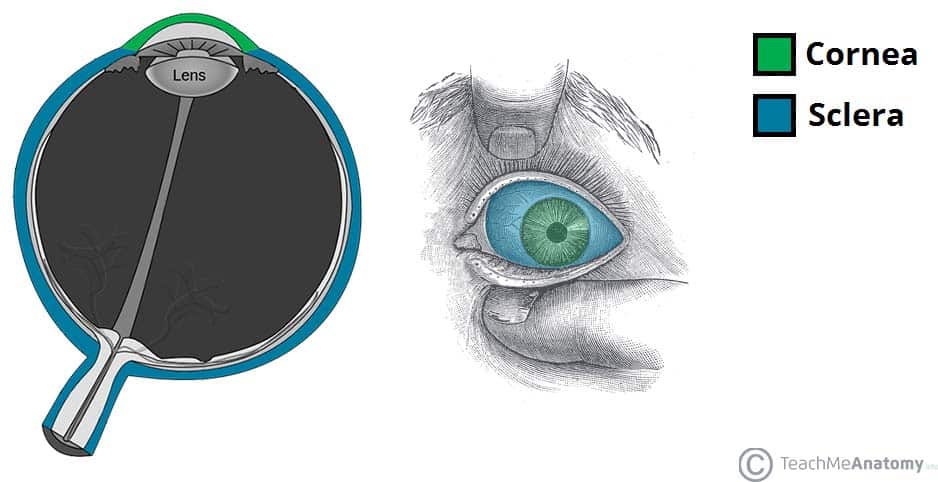

The fibrous layer of the eye is the outermost layer. It consists of the sclera and cornea, which are continuous with each other. Their main functions are to provide shape to the eye and support the deeper structures.

The sclera comprises the majority of the fibrous layer (approximately 85%). It provides attachment to the extraocular muscles – these muscles are responsible for the movement of the eye. It is visible as the white part of the eye.

The cornea is transparent and positioned centrally at the front of the eye. Light entering the eye is refracted by the cornea.

Vascular

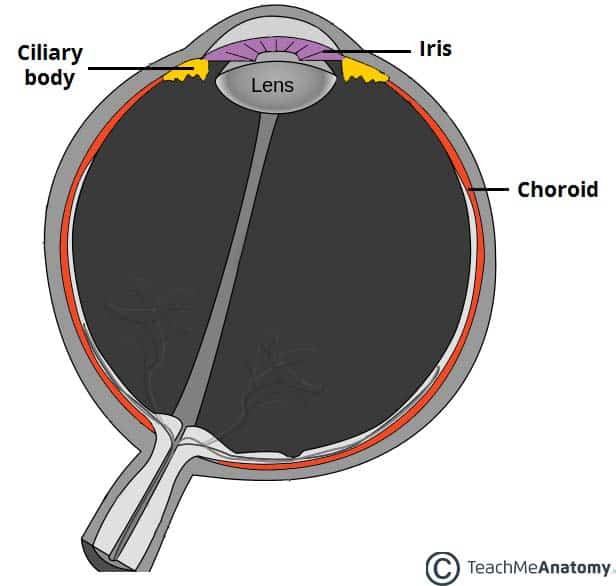

The vascular layer of the eye lies underneath the fibrous layer. It consists of the choroid, ciliary body and iris:

- Choroid – layer of connective tissue and blood vessels. It provides nourishment to the outer layers of the retina.

- Ciliary body – comprised of two parts – the ciliary muscle and ciliary processes. The ciliary muscle consists of a collection of smooth muscles fibres. These are attached to the lens of the eye by the ciliary processes. The ciliary body controls the shape of the lens, and contributes to the formation of aqueous humor

- Iris – circular structure, with an aperture in the centre (the pupil). The diameter of the pupil is altered by smooth muscle fibres within the iris, which are innervated by the autonomic nervous system. It is situated between the lens and the cornea.

Inner

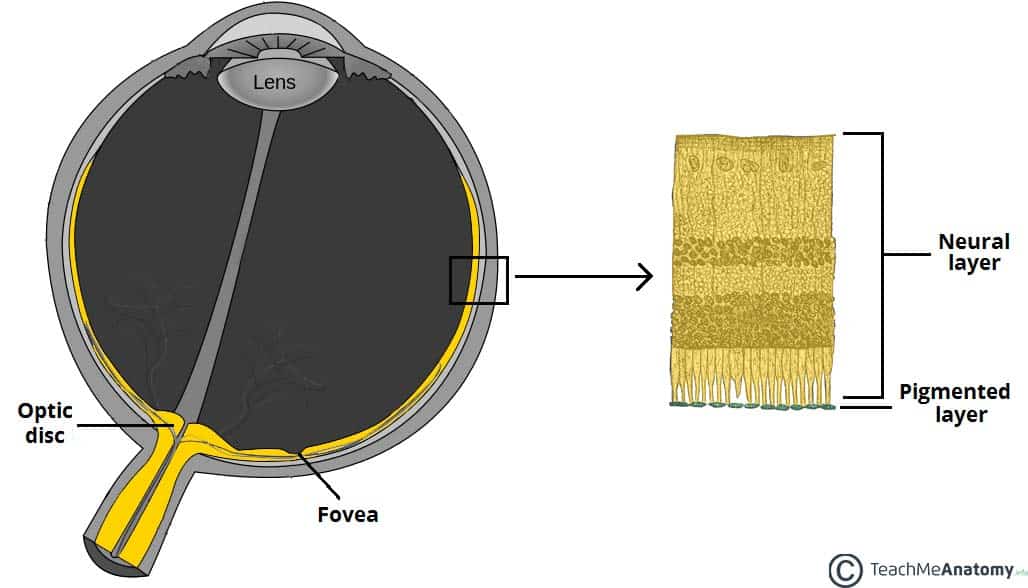

The inner layer of the eye is formed by the retina; its light detecting component. The retina is composed of two layers:

- Pigmented (outer) layer – formed by a single layer of cells. It is attached to the choroid and supports the choroid in absorbing light (preventing scattering of light within the eyeball). It continues around the whole inner surface of the eye.

- Neural (inner) layer – consists of photoreceptors, the light detecting cells of the retina. It is located posteriorly and laterally in the eye.

Anteriorly, the pigmented layer continues but the neural layer does not – this is part is known as the non-visual retina. Posteriorly and laterally, both layers of the retina are present. This is the optic part of the retina.

The optic part of the retina can be viewed during ophthalmoscopy. The centre of the retina is marked by an area known as the macula. It is yellowish in colour, and highly pigmented. The macula contains a depression called the fovea centralis, which has a high concentration of light detecting cells. It is the area responsible for high acuity vision. The area that the optic nerve enters the retina is known as the optic disc – it contains no light detecting cells.

Structures of the Eyeball

Vitreous Body

The vitreous body is a transparent gel which fills the posterior segment of the eyeball (the area posterior to the lens).

It is marked by a narrow canal which runs from the optic disc to the lens – the hyaloid canal. This is a fetal remnant.

The vitreous body has three main functions:

- Contributes to the magnifying power of the eye

- Supports the lens

- Holds the layers of the retina in place

Lens

The lens of the eye is located anteriorly, between the vitreous humor and the pupil. The shape of the lens is altered by the ciliary body, altering its refractive power. In old age, the lens can become opaque – a condition known as a cataract.

Anterior and Posterior Chambers

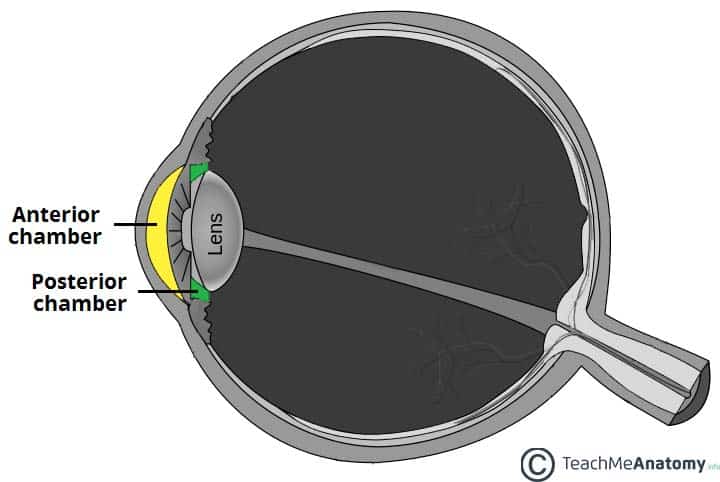

There are two fluid filled areas in the eye – known as the anterior and posterior chambers. The anterior chamber is located between the cornea and the iris, and the posterior chamber between the iris and ciliary processes.

The chambers are filled with aqueous humor – a clear plasma-like fluid that nourishes and protects the eye. The aqueous humor is produced constantly, and drains via the trabecular meshwork, an area of tissue at the base of the cornea, near the anterior chamber.

If the drainage of aqueous humor is obstructed, a condition known as glaucoma can result.

Vasculature

The eyeball receives arterial blood primarily via the ophthalmic artery. This is a branch of the internal carotid artery, arising immediately distal to the cavernous sinus. The ophthalmic artery gives rise to many branches, which supply different components of the eye. The central artery of the retina is the most important branch – supplying the internal surface of the retina. Occlusion of this artery will quickly result in blindness.

Venous drainage of the eyeball is carried out by the superior and inferior ophthalmic veins. These drain into the cavernous sinus, a dural venous sinus in close proximity to the eye.

Clinical Relevance: Glaucoma

Glaucoma refers to a group of eye diseases that result in damage to the optic nerve. There are two main clinical classifications of glaucoma:

- Open angle – where the outflow of aqueous humor through the trabecular meshwork is reduced. It causes a gradual reduction of the peripheral vision, until the end stages of the disease.

- Closed angle – where the iris is forced against the trabecular meshwork, preventing any drainage of aqueous humor. It is an ophthalmic emergency, which can rapidly lead to blindness.

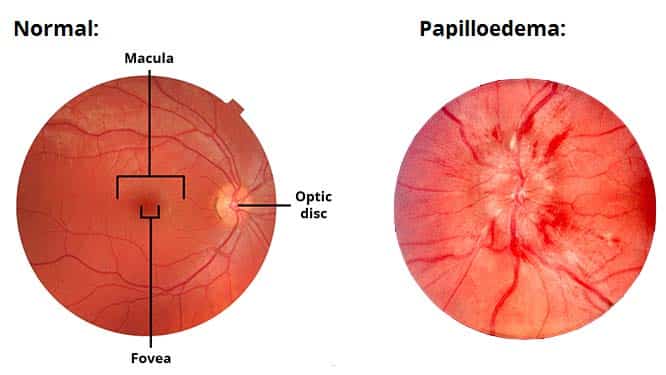

Clinical Relevance: Papilloedema

Papilloedema refers to swelling of the optic disc that occurs secondary to raised intracranial pressure. The optic disc is the area of the retina where the optic nerve enters and can be visualised using an ophthalmoscope.

Common causes include:

- Intracerebral mass lesions

- Cerebral haemorrhage

- Meningitis

- Hydrocephalus

In papilloedema, the high pressure within the cranium resists venous return from the eye. This causes fluid to extravasate from blood vessels and collect in the retina, producing a swollen optic disc.