The diaphragm is a double-domed musculotendinous sheet, located at the inferior-most aspect of the rib cage. It serves two main functions:

- Separates the thoracic cavity from the abdominal cavity (the word diaphragm is derived from the Greek ‘diáphragma’, meaning partition).

- Undergoes contraction and relaxation, altering the volume of the thoracic cavity and the lungs, producing inspiration and expiration.

In this article, we shall look at the anatomy of the diaphragm – its attachments, actions and associated neurovascular structures.

Anatomical Position and Attachments

The diaphragm is located at the inferior-most aspect of the ribcage, filling the inferior thoracic aperture. It acts as the floor of the thoracic cavity and the roof of the abdominal cavity. The attachments of diaphragm can be divided into peripheral and central attachments. It has three peripheral attachments:

- Lumbar vertebrae and arcuate ligaments.

- Costal cartilages of ribs 7-10 (attach directly to ribs 11-12).

- Xiphoid process of the sternum.

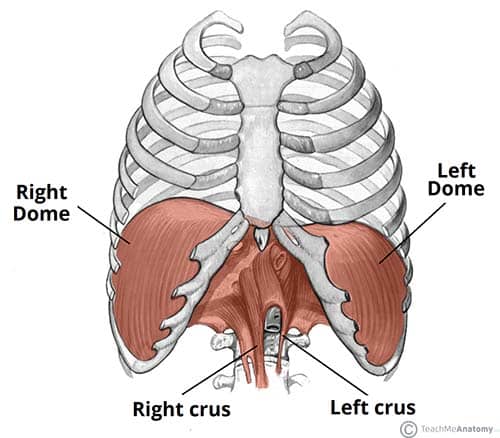

The parts of the diaphragm that arise from the vertebrae are tendinous in structure, and are known as the right and left crura:

- Right crus – Arises from L1-L3 and their intervertebral discs. Some fibres from the right crus surround the oesophageal opening, acting as a physiological sphincter to prevent reflux of gastric contents into the oesophagus.

- Left crus – Arises from L1-L2 and their intervertebral discs.

The muscle fibres of the diaphragm combine to form a central tendon. This tendon ascends to fuse with the inferior surface of the fibrous pericardium. Either side of the pericardium, the diaphragm ascends to form left and right domes. At rest, the right dome lies slightly higher than the left – this is thought to be due to the presence of the liver.

Fig 1 – The diaphragm is split into two lobes, left and right. Note the vertebral attachments of the diaphragm are the left and right crura.

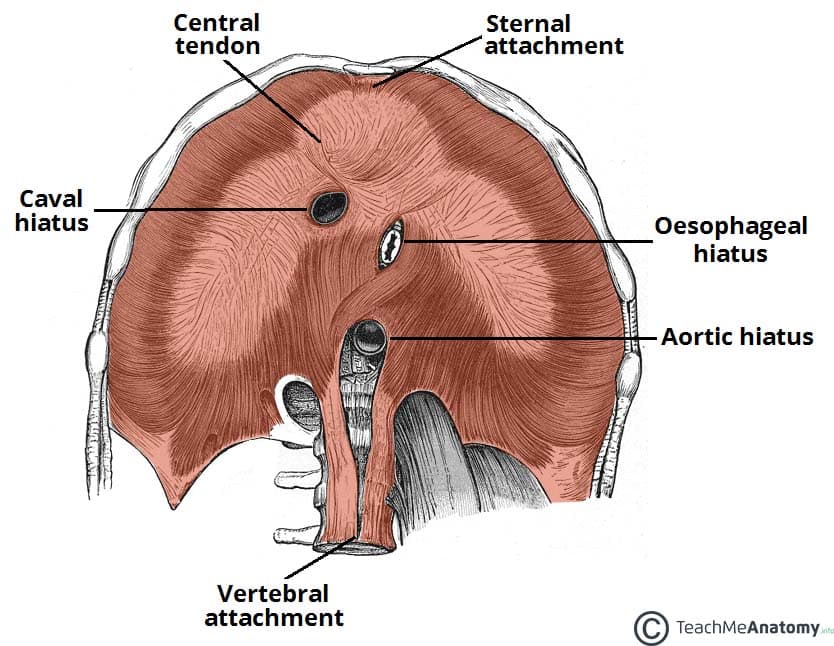

Pathways through the Diaphragm

The diaphragm divides the thoracic and abdominal cavities. Thus, any structure that pass between the two cavities will pierce the diaphragm.

There are three openings that act as conduit for these structures:

| Caval Hiatus (T8) | Oesophageal Hiatus (T10) | Aortic Hiatus (T12) |

|

|

|

Fig 2 – View of the inferior surface of the diaphragm. Note the three openings.

Actions

The diaphragm is the primary muscle of respiration. During inspiration, it contracts and flattens, increasing the vertical diameter of the thoracic cavity. This produces lung expansion, and air is drawn in.

During expiration, the diaphragm passively relaxes and returns to its original dome shape. This reduces the volume of the thoracic cavity.

Innervation and Vasculature

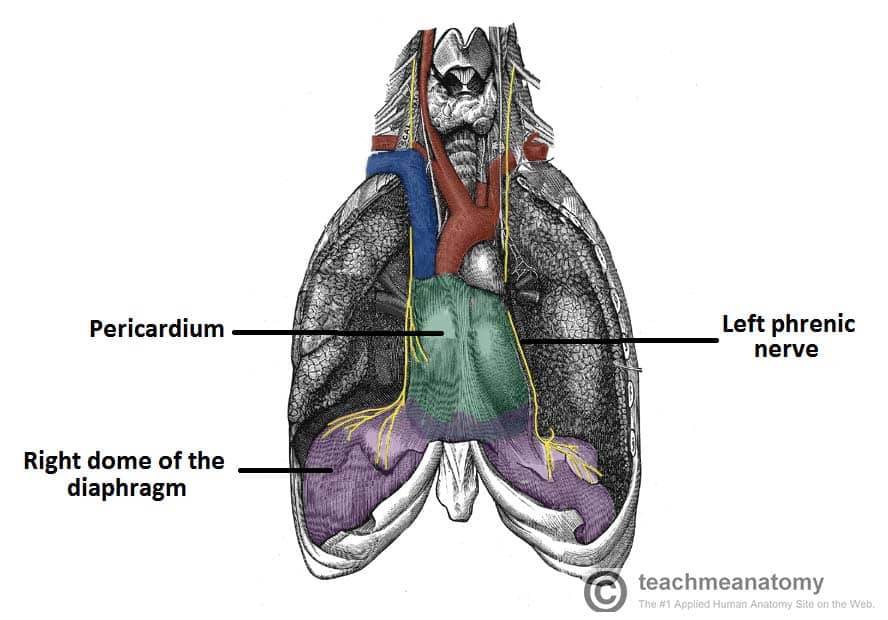

The halves of the diaphragm receive motor innervation from the phrenic nerve. The left half of the diaphragm (known as a hemidiaphragm) is innervated by the left phrenic nerve, and vice versa. Each phrenic nerve is formed in the neck within the cervical plexus and contains fibres from spinal roots C3-C5.

The majority of the arterial supply to the diaphragm is delivered via the inferior phrenic arteries, which arise directly from the abdominal aorta. The remaining supply is from the superior phrenic, pericardiacophrenic, and musculophrenic arteries. The draining veins follow the aforementioned arteries.

Fig 3 – The anatomical course of the phrenic nerves, which innervate the diaphragm.

Clinical Relevance: Paralysis of the Diaphragm

Diaphragmatic paralysis is due to an interruption in its nervous supply. This can occur in the phrenic nerve, cervical spinal cord, or the brainstem. It is most often due to a lesion of the phrenic nerve:

- Mechanical trauma: ligation or damage to the nerve during surgery.

- Compression: due to a tumour within the chest cavity.

- Myopathies: such as myasthenia gravis.

- Neuropathies: such diabetic neuropathy.

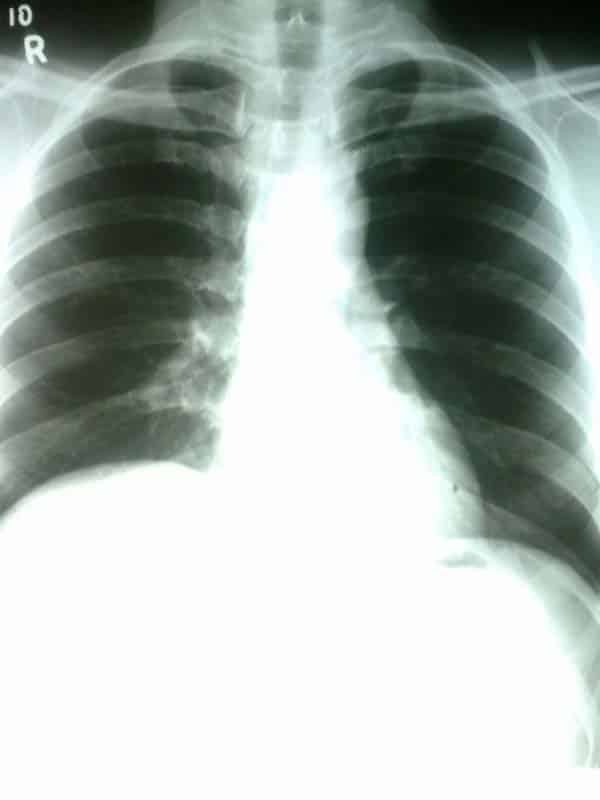

Paralysis of the diaphragm produces a paradoxical movement. The affected side of the diaphragm moves upwards during inspiration, and downwards during expiration. A unilateral diaphragmatic paralysis is usually asymptomatic and is most often an incidental finding on x-ray. If both sides are paralysed, the patient may experience poor exercise tolerance, orthopnoea and fatigue. Lung function tests will show a restrictive deficit.

Management of diaphragmatic paralysis is two-fold. Firstly, the underlying cause must be identified and treated. The second part of treatment deals with symptomatic relief. This is usually via non-invasive ventilation, such as a CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure) machine.