The skin is the largest organ in the human body and comprises approximately 8% of total body mass.

It is a versatile structure with a wide range of functions; and its exact composition varies across different regions of the body’s surface.

In this article, we will discuss the function, gross structure and ultrastructure of our skin.

Functions of Skin

The skin provides an essential barrier between the external environment and internal body contents. It protects against mechanical, chemical, osmotic, thermal, and UV damage, and microbial invasion.

Its other functions include:

- A role in the synthesis of vitamin D

- Regulation of body temperature

- Psychosexual communication

- A major sensory organ for touch, temperature, pain, and other stimuli.

Gross Structure

The composition of skin varies across the surface of the body. Skin can be thin, hairy, hirsute, or glabrous. Glabrous skin is the thick skin found over the palms, soles of the feet and flexor surfaces of the fingers that is free from hair.

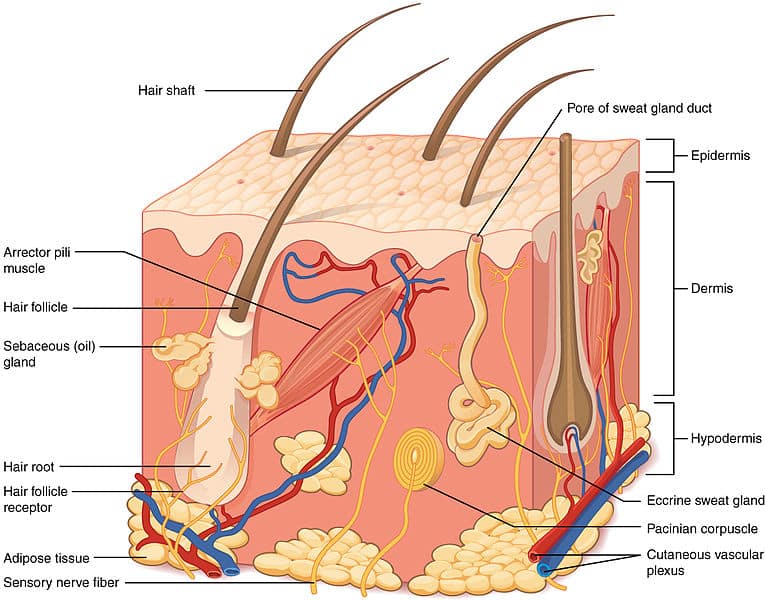

Throughout the body, skin is composed of three layers; the epidermis, dermis and hypodermis. We shall now examine these layers in more detail.

Ultrastructure

Epidermis

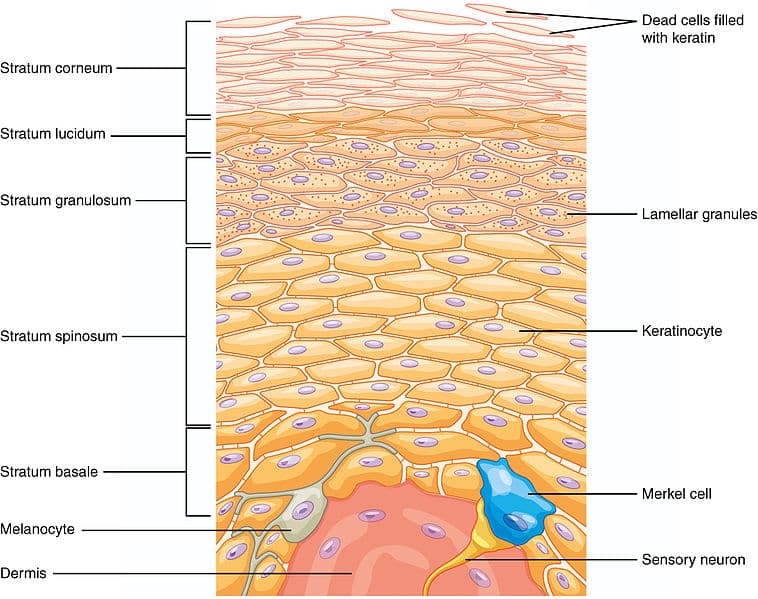

The epidermis is the most superficial layer of the skin, and is largely formed by layers of keratinocytes undergoing terminal maturation. This involves increased keratin production and migration toward the external surface, a process termed cornification.

There are also several non-keratinocyte cells that inhabit the epidermis:

- Melanocytes – responsible for melanin production and pigment formation.

- Note – individuals with darker skin have increased melanin production, not an increased number of melanocytes.

- Langerhans cells – antigen-presenting dendritic cells.

- Merkel cells – sensory mechanoreceptors.

Layers of the Epidermis

The epidermis can be divided into layers (strata) of keratinocytes – this reflects their change in structure and properties as they migrate towards the surface. From deepest to most superficial, these layers are:

- Stratum basale – mitosis of keratinocytes occurs in this layer.

- Stratum spinosum – keratinocytes are joined by tight intercellular junctions called desmosomes.

- Stratum granulosum – cells secrete lipids and other waterproofing molecules in this layer.

- Stratum lucidum – cells lose nuclei and drastically increase keratin production.

- Stratum corneum – cells lose all organelles, continue to produce keratin.

A keratinocyte typically takes between 30 – 40 days to travel from the stratum basale to the stratum corneum.

Fig 2 – The layers of the epidermis are formed by keratinocytes at different levels of maturation.

Dermis

The dermis is immediately deep to the epidermis and is tightly connected to it through a highly-corrugated dermo-epidermal junction.

The dermis has only two layers, which are less clearly defined than the layers of the epidermis. They are the superficial papillary layer, and the deeper reticular layer. The reticular layer is considerably thicker, and features thicker bundles of collagen fibres that provide more durability.

The following cell types and structures can be found in the dermis:

- Fibroblasts – these cells synthesise the extracellular matrix, which is predominantly composed of collagen and elastin.

- Mast cells – these are histamine granule-containing cells of the innate immune system.

- Blood vessels and cutaneous sensory nerves

- Skin appendages – e.g. hair follicles, nails, sebaceous and sweat glands. Although present in the dermis, these structures are derived from the epidermis which descend into the dermis during development.

Hair Follicles and Sebaceous Glands

The hair follicles and sebaceous glands combine to form a pilosebaceous unit – which is only found on hirsute skin.

Sebaceous glands release their glandular secretions via a holocrine mechanism into the hair follicle shaft. The hair follicle itself is associated with an arrector pili muscle, which contracts to cause the follicle to stand upright.

Sweat Glands

There are two main types of sweat glands:

- Eccrine glands – the major sweat glands of the human body. They release a clear, odourless substance, comprised mostly of sodium chloride and water – which is involved in thermoregulation.

- Apocrine glands – larger sweat glands, located in the axillary and genital regions. These apocrine glandular products can be broken down by cutaneous microbes, producing body odour.

Hypodermis

The hypodermis, or subcutaneous tissue, is immediately deep to the dermis.

It is a major body store of adipose tissue, and as such can vary in size between individuals depending on the amount of fatty tissue present.

Clinical Relevance – Disorders of Skin

- Alopecia Areata – alopecia is marked by autoimmune destruction of hair follicles, causing hair loss.

- Vitiligo – Like alopecia, vitiligo is an autoimmune disease, where melanocytes are targeted and destroyed. Areas of symmetrical depigmentation appear, which are more apparent in darker-skinned individuals.

- Psoriasis – In psoriasis, the mitosis of keratinocytes in the stratum basale is drastically increased, producing a thickened stratum spinosum. This is clinically apparent as “scaly” skin, typically on the knees and elbows.