The pelvic cavity contains the organs of reproduction, urinary bladder, pelvic colon, rectum and numerous muscles. Its arterial supply is largely via the internal iliac artery, with some smaller arteries providing additional supply.

In this article we will look at the anatomy of the pelvic arteries, detailing their anatomical course, branches and their clinical relevance.

Major Arteries of the Pelvis: Internal Iliac

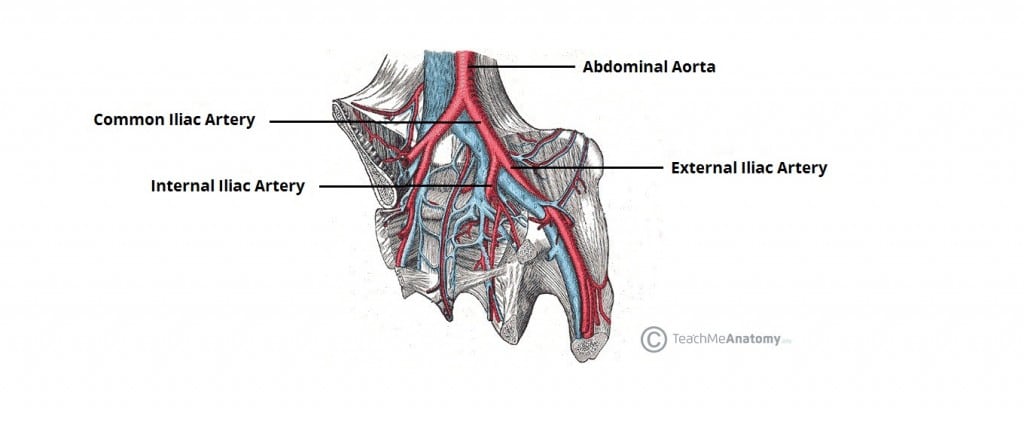

The internal iliac artery is the major artery of the pelvis. It originates at the bifurcation of the common iliac artery into its internal and external branches, as shown in Figure 1. This approximately occurs at vertebral level L5-S1.

The artery descends inferiorly, crossing the pelvic inlet to enter the lesser pelvis. During its descent, it is situated medially to the external iliac vein and obturator nerve. At the superior border of the greater sciatic foramen, it divides into anterior and posterior trunks.

Figure 1 – The bifurcation of the common iliac artery into internal and external branches.

Anterior Trunk

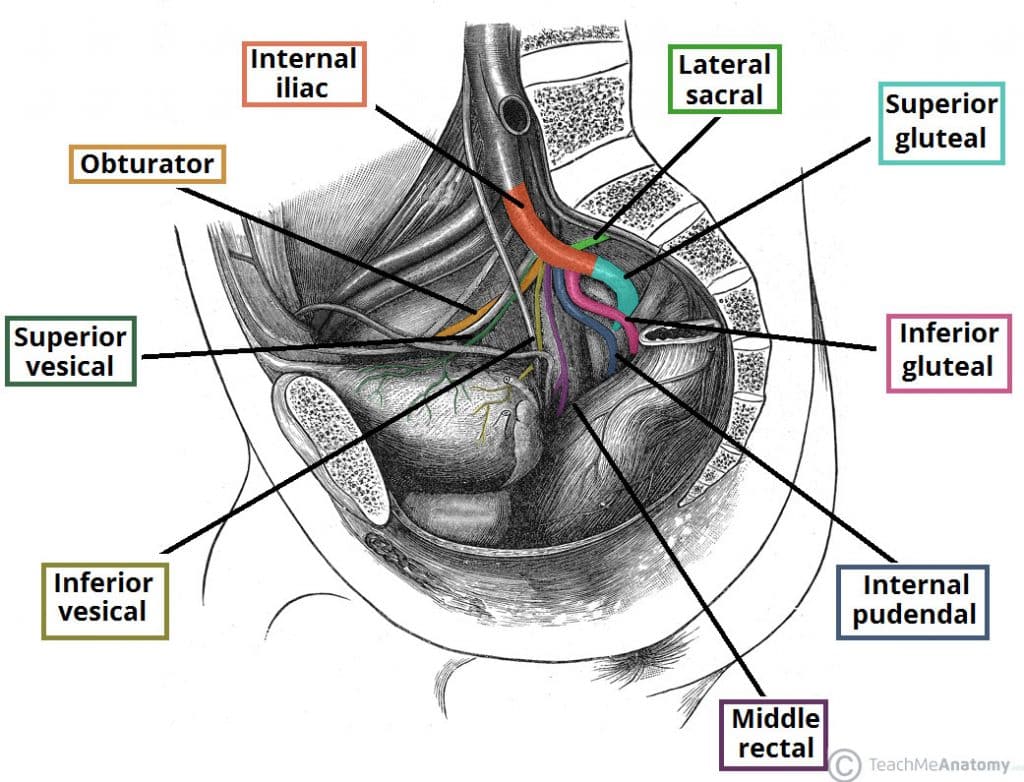

The anterior trunk gives rise to numerous branches that supply the pelvic organs, the perineum, and the gluteal and adductor regions of the lower limb. The following branches of the internal iliac artery are highlighted in Figure 2 below, working anti-clockwise from obturator artery to inferior gluteal artery.

- Obturator artery – Travels through the obturator canal, accompanied by the obturator nerve and vein. It supplies the muscles of the thigh’s adductor region.

- Umbilical artery – Gives rise to the superior vesical artery, which supplies the superior aspect of the urinary bladder.

- In utero, the umbilical artery transports deoxygenated blood from the fetus to the placenta.

- Inferior vesical artery – Supplies the lower aspect of the bladder. In males, it also supplies the prostate gland and seminal vesicles.

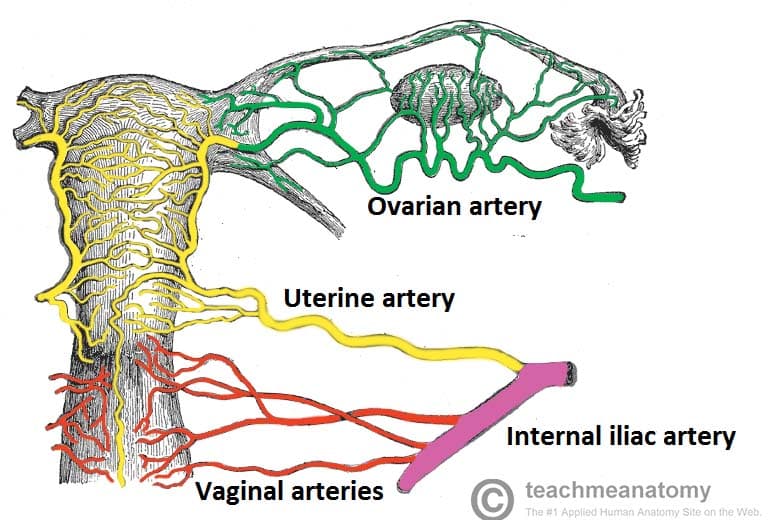

- Vaginal artery (female) – Descends to the vagina, supplying additional branches to the inferior bladder and rectum.

- Uterine artery (female) (shown in Figure 3) – Travels within the cardinal ligament to reach the cervix, where it ascends along the lateral aspect of the uterus. At origin of the fallopian tubes, it anastomoses with the ovarian artery. During its course, it crosses the ureters superiorly.

- Middle rectal artery – Travels medially to supply the distal part of the rectum. It also forms anastomoses with the superior rectal artery (derived from the inferior mesenteric) and the inferior rectal artery (derived from the internal pudendal)

- Internal pudendal artery – Moves inferiorly to exit the pelvis via the greater sciatic foramen. Accompanied by the pudendal nerve, it then enters the perineum via the lesser sciatic foramen. It is the main artery responsible for the blood supply to the perineum.

- Inferior gluteal artery – The terminal branch of the anterior trunk. It leaves the pelvic cavity via the greater sciatic foramen, emerging inferiorly to the piriformis muscle in the gluteal region. It contributes to the blood supply of the gluteal muscles and hip joint.

Figure 2 – The major branches of the internal iliac artery. Anterior branches are shown from obturator artery, moving anti-clockwise to the inferior gluteal artery. The lateral sacral artery and superior gluteal artery arise from the posterior trunk. Note: The anterior and posterior trunks are not visible in this illustration

Posterior Trunk

The posterior trunk gives rise to arteries that supply the lower posterior abdominal wall, posterior pelvic wall and the gluteal region. There are typically three branches:

- Iliolumbar artery – Ascends to exit the lesser pelvis, dividing into a lumbar and iliac branch. The lumbar branch supplies psoas major, quadratus lumborum and the posterior abdominal wall. The iliac branch supplies the muscles and bone around the iliac fossa.

- Lateral sacral arteries (superior and inferior) – Travel infero-medially along the posterior pelvic wall to supply structures in the sacral canal, and the skin and muscle posterior to the sacrum.

- Superior gluteal artery – The terminal branch of the posterior trunk. It exits the pelvic cavity via the greater sciatic foramen, entering the gluteal region superiorly to the piriformis muscle. It is the major blood supply to the muscles and skin of the gluteal region.

Minor Arteries of the Pelvis

Gonadal Arteries

The ovarian artery is the major gonadal artery in females. It arises from the abdominal aorta, distal to the origin of the renal arteries. The artery descends towards the pelvis, crossing the pelvic brim and the origin of the external iliac vessels. It moves medially, dividing into an ovarian branch and tubal branches, which supply their respective structures.

Note – the testicular artery reaches the scrotum via the inguinal canal, and therefore does not actually enter the pelvis.

Figure 3 – Arterial supply to the female reproductive tract. The uterine and vaginal arteries come from the anterior branch of the internal iliac artery, while the ovarian artery arises from the abdominal aorta.

Median Sacral Artery

The median sacral artery originates from the posterior aspect of abdominal aorta, at its bifurcation into the common iliac arteries. It descends anteriorly to the L4 and L5 vertebrae, the sacrum and the coccyx, contributing to the arterial supply of these regions.

Superior Rectal Artery

The superior rectal artery is the terminal continuation of the inferior mesenteric artery. It crosses the left common iliac artery and descends in the mesentery of the sigmoid colon. It gives rise to branches that supply the rectum.

Clinical Correlation: Hysterectomy

A hysterectomy is the surgical removal of the uterus. It has a number of possible indications. The following are the most common, but this is not an exhaustive list:

- Heavy menstrual bleeding

- Pelvic pain

- Uterine prolapse (vaginal hysterectomy)

- Gynaecological malignancy (usually ovarian, uterine or cervical)

- Risk reducing surgery, usually in cases of BRCA 1 or 2 mutations, or Lynch syndrome.

When performing a hysterectomy, a good knowledge of regional anatomy is needed to prevent accidentally damaging other structures in the pelvic region.

The uterine artery crosses the ureters approximately 1 cm laterally to the internal os of the cervix. Care must be taken not to damage the ureters during clamping of the uterine arteries during a hysterectomy. The relationship between the two can be remembered using the phrase ‘water under the bridge’. Water refers to the ureter (urine), and the uterine artery is the bridge.