The pelvic girdle is a ring-like bony structure, located in the lower part of the trunk. It connects the axial skeleton to the lower limbs.

In this article, we shall look at the anatomy of the pelvic girdle – its bony landmarks, functions, and its clinical relevance.

Structure of the Pelvic Girdle

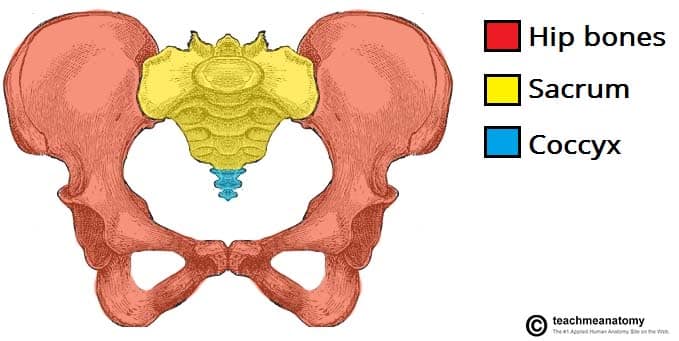

The bony pelvis consists of the two hip bones (also known as innominate or pelvic bones), the sacrum and the coccyx.

There are four articulations within the pelvis:

- Sacroiliac joints (x2) – between the ilium of the hip bones, and the sacrum

- Sacrococcygeal symphysis – between the sacrum and the coccyx.

- Pubic symphysis – between the pubis bodies of the two hip bones.

Ligaments attach the lateral border of the sacrum to various bony landmarks on the bony pelvis to aid stability.

Fig 1 – The pelvic girdle is formed by the hip bones, sacrum and coccyx.

Functions of the Pelvis

The strong and rigid pelvis is adapted to serve a number of roles in the human body. The main functions being:

- Transfer of weight from the upper axial skeleton to the lower appendicular components of the skeleton, especially during movement.

- Provides attachment for a number of muscles and ligaments used in locomotion.

- Contains and protects the abdominopelvic and pelvic viscera.

The Greater and Lesser Pelvis

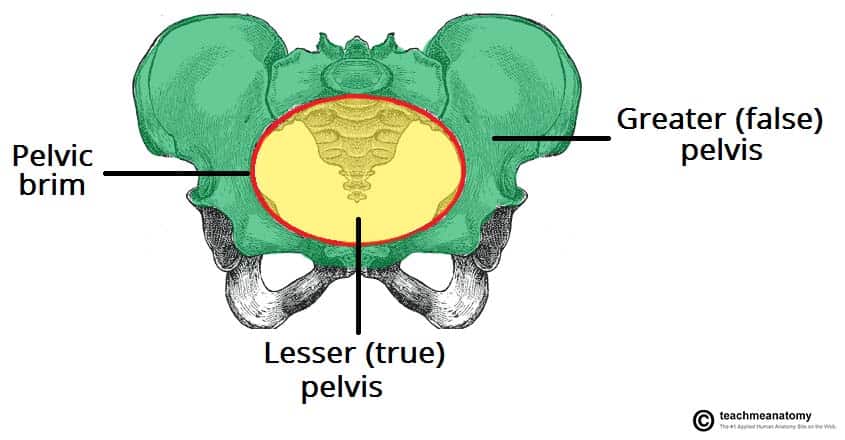

The osteology of the pelvic girdle allows the pelvic region to be divided into two:

- Greater pelvis (false pelvis) – located superiorly, it provides support of the lower abdominal viscera (such as the ileum and sigmoid colon). It has little obstetric relevance.

- Lesser pelvis (true pelvis) – located inferiorly. Within the lesser pelvis reside the pelvic cavity and pelvic viscera.

The junction between the greater and lesser pelvis is known as the pelvic inlet. The outer bony edges of the pelvic inlet are called the pelvic brim.

Fig 2 – The greater and lesser pelvis. The lesser pelvis is the ‘true’ pelvis and contains the pelvic cavity.

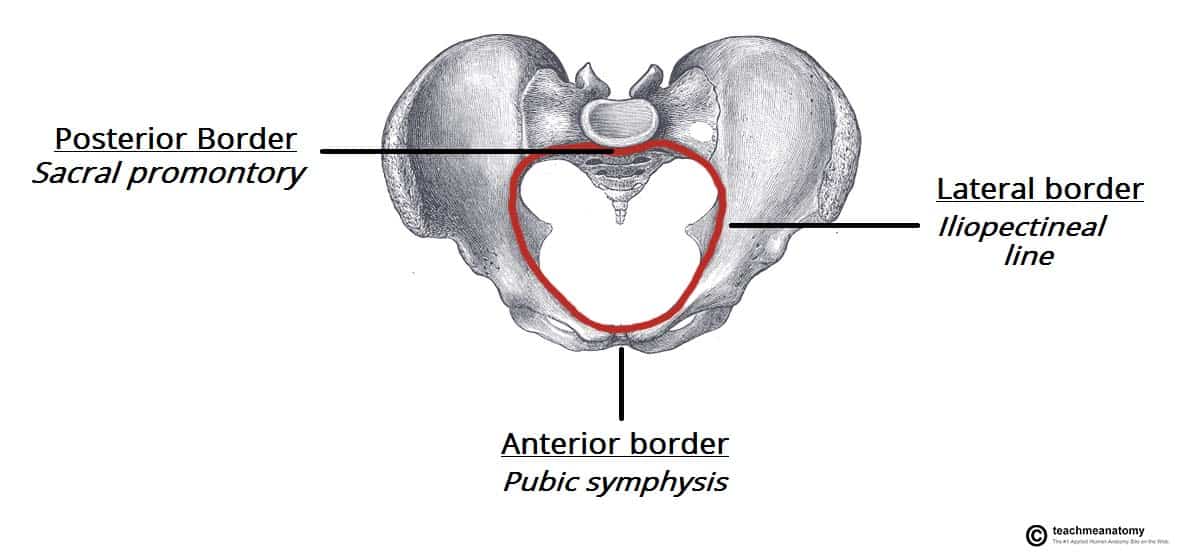

Pelvic Inlet

The pelvic inlet marks the boundary between the greater pelvis and lesser pelvis. Its size is defined by its edge, the pelvic brim.

The borders of the pelvic inlet:

- Posterior – sacral promontory (the superior portion of the sacrum) and sacral wings (ala).

- Lateral – arcuate line on the inner surface of the ilium, and the pectineal line on the superior pubic ramus.

- Anterior – pubic symphysis.

The pelvic inlet determines the size and shape of the birth canal, with the prominent ridges a key site for attachment of muscle and ligaments.

Some alternative descriptive terminology can be used in describing the pelvic inlet:

- Linea terminalis – the combined pectineal line, arcuate line and sacral promontory.

- Iliopectineal line – the combined arcuate and pectineal lines. This represents the lateral border of the pelvic inlet.

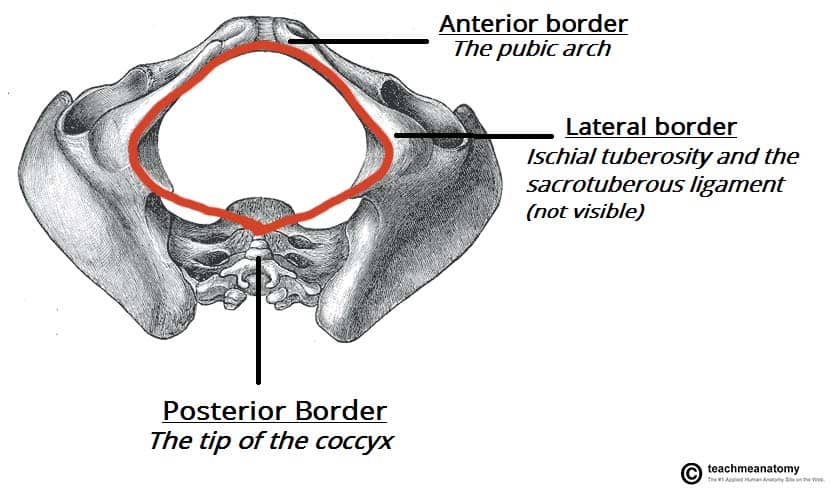

Pelvic Outlet

The pelvic outlet is located at the end of the lesser pelvis, and the beginning of the pelvic wall.

Its borders are:

- Posterior: The tip of the coccyx

- Lateral: The ischial tuberosities and the inferior margin of the sacrotuberous ligament

- Anterior: The pubic arch (the inferior border of the ischiopubic rami).

The angle beneath the pubic arch is known as the sub-pubic angle and is of a greater size in women.

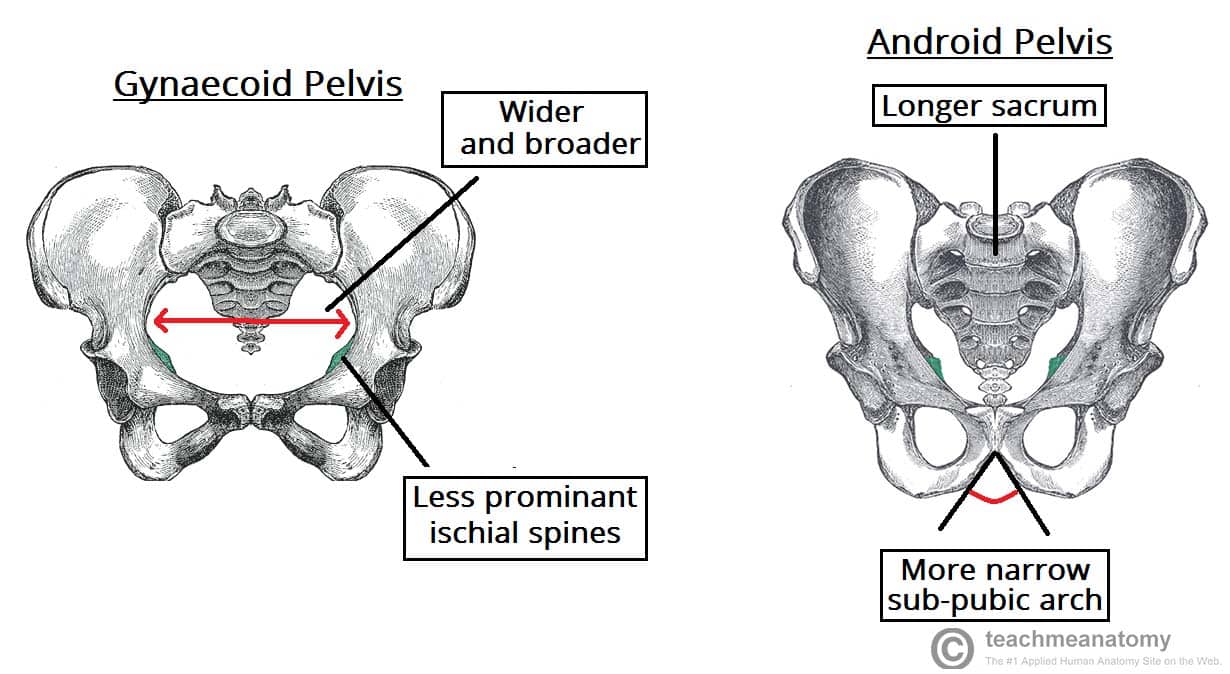

Adaptation for Childbirth

The majority of women have a gynaecoid pelvis, as opposed to the male android pelvis. The slight differences in their structures creates a greater pelvic outlet, adapted to aid the process of childbirth. When comparing the two, the gynaecoid pelvis has:

- A wider and broader structure yet it is lighter in weight

- An oval-shaped inlet compared with the heart-shaped android pelvis.

- Less prominent ischial spines, allowing for a greater bispinous diameter

- A greater angled sub-pubic arch, more than 80-90 degrees.

- A sacrum which is shorter, more curved and with a less pronounced sacral promontory.

In addition to the bony adaptations, the sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments can stretch under the influence of progesterone and increase the size of the outlet further.

Clinical Relevance: Assessment of the Female Bony Pelvis

The lesser pelvis is the bony canal through which the fetus has to pass during childbirth. It is therefore of great importance to determine the diameter of this canal and therefore the childbearing capacity of the mother.

The diameter can be determined by a pelvic examination or radiographically. There are two measurements that are of importance:

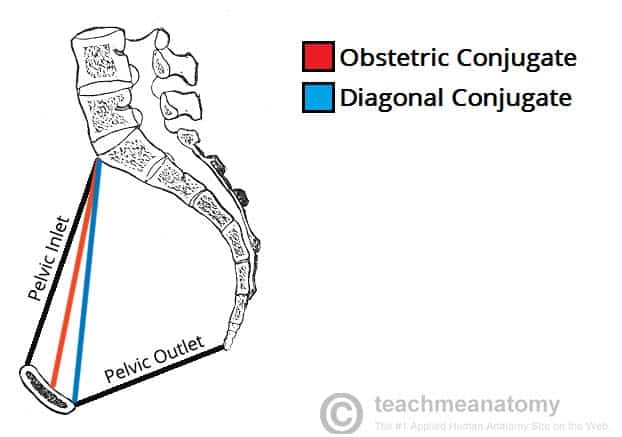

Obstetric Conjugate

In order to determine the narrowest fixed distance that the fetus would have to negotiate, the minimum antero-posterior diameter of the pelvic inlet is measured.

This distance is between the sacral promontory and the midpoint of the pubic symphysis (where the pubic bone is thickest) and is known as the obstetric conjugate (or true conjugate). However, this measurement cannot be assessed clinically, due to the presence of the bladder.

Diagonal Conjugate

The diagonal conjugate is the alternative, measuring from the inferior border of the pubic symphysis to the sacral promontory and can be measured manually via the vagina.

(To do this you use the tip of your middle finger to measure the sacral promontory and then using the other hand to mark the level of the inferior margin of the pubic symphysis on the examining hand. You then use the distance between the index finger and the pubic symphysis to measure the diagonal conjugate, ideally 11cm or greater)

In addition to measuring the diagonal conjugate, a mid-pelvis check is carried out. Here, the clinician is testing for straight side walls and measuring the bispinous diameter which is narrowest part of the pelvic canal. The width of the subpubic angle at the pelvic outlet can be determined by the distance between the ischial tuberosities.