The cerebellum, which stands for “little brain”, is a structure of the central nervous system. It has an important role in motor control, with cerebellar dysfunction often presenting with motor signs. In particular, it is active in the coordination, precision and timing of movements, as well as in motor learning.

During embryonic development, the anterior portion of the neural tube forms three parts that give rise to the brain and associated structures:

- Forebrain (prosencephalon)

- Midbrain (mesencephalon)

- Hindbrain (rhombencephalon)

The hindbrain subsequently divides into the metencephalon (superior) and the myelencephalon (inferior). The cerebellum develops from the metencephalon division.

This article will focus on the anatomy of the cerebellum. It will provide a brief overview of its functions and development, and finally it will highlight the clinical relevance of cerebellar disorders.

Anatomical Location

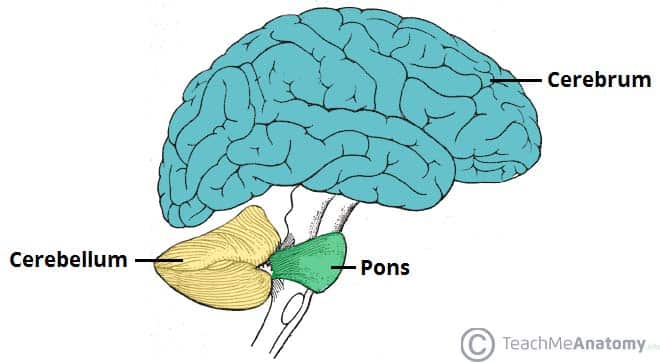

The cerebellum is located at the back of the brain, immediately inferior to the occipital and temporal lobes, and within the posterior cranial fossa. It is separated from these lobes by the tentorium cerebelli, a tough layer of dura mater.

It lies at the same level of and posterior to the pons, from which it is separated by the fourth ventricle.

Fig 1 – Anatomical position of the cerebellum. It is inferior to the cerebrum, and posterior to the pons.

Anatomical Structure and Divisions

The cerebellum consists of two hemispheres which are connected by the vermis, a narrow midline area. Like other structures in the central nervous system, the cerebellum consists of grey matter and white matter:

- Grey matter – located on the surface of the cerebellum. It is tightly folded, forming the cerebellar cortex.

- White matter – located underneath the cerebellar cortex. Embedded in the white matter are the four cerebellar nuclei (the dentate, emboliform, globose, and fastigi nuclei).

There are three ways that the cerebellum can be subdivided – anatomical lobes, zones and functional divisions

Anatomical Lobes

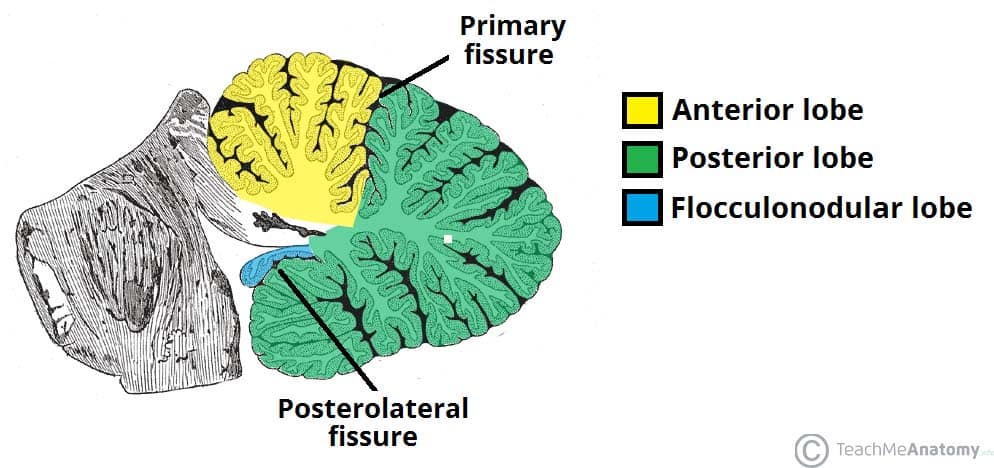

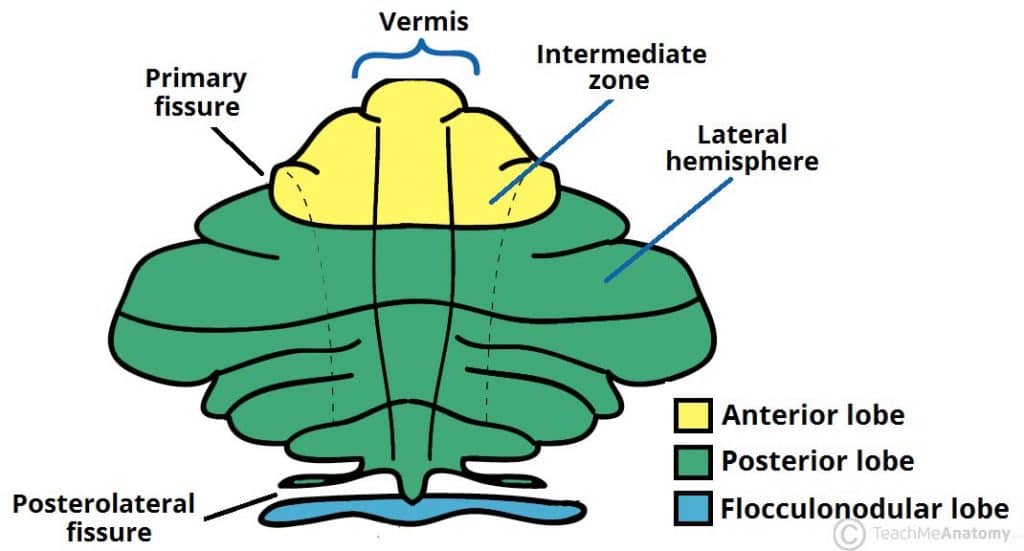

There are three anatomical lobes that can be distinguished in the cerebellum; the anterior lobe, the posterior lobe and the flocculonodular lobe. These lobes are divided by two fissures – the primary fissure and posterolateral fissure.

Zones

There are three cerebellar zones. In the midline of the cerebellum is the vermis. Either side of the vermis is the intermediate zone. Lateral to the intermediate zone are the lateral hemispheres. There is no difference in gross structure between the lateral hemispheres and intermediate zones

Fig 3 – Superior view of an “unrolled” cerebellum, placing the vermis in one plane.

Functional Divisions

The cerebellum can also be divided by function. There are three functional areas of the cerebellum – the cerebrocerebellum, the spinocerebellum and the vestibulocerebellum.

- Cerebrocerebellum – the largest division, formed by the lateral hemispheres. It is involved in planning movements and motor learning. It receives inputs from the cerebral cortex and pontine nuclei, and sends outputs to the thalamus and red nucleus. This area also regulates coordination of muscle activation and is important in visually guided movements.

- Spinocerebellum – comprised of the vermis and intermediate zone of the cerebellar hemispheres. It is involved in regulating body movements by allowing for error correction. It also receives proprioceptive information.

- Vestibulocerebellum – the functional equivalent to the flocculonodular lobe. It is involved in controlling balance and ocular reflexes, mainly fixation on a target. It receives inputs from the vestibular system, and sends outputs back to the vestibular nuclei.

Vasculature

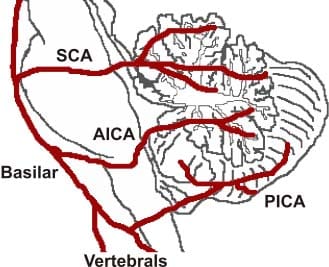

The cerebellum receives its blood supply from three paired arteries:

- Superior cerebellar artery (SCA)

- Anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA)

- Posterior inferior cerebellar artery (PICA)

The SCA and AICA are branches of the basilar artery, which wraps around the anterior aspect of the pons before reaching the cerebellum. The PICA is a branch of the vertebral artery.

Venous drainage of the cerebellum is by the superior and inferior cerebellar veins. They drain into the superior petrosal, transverse and straight dural venous sinuses.

Clinical Relevance: Cerebellar Dysfunction

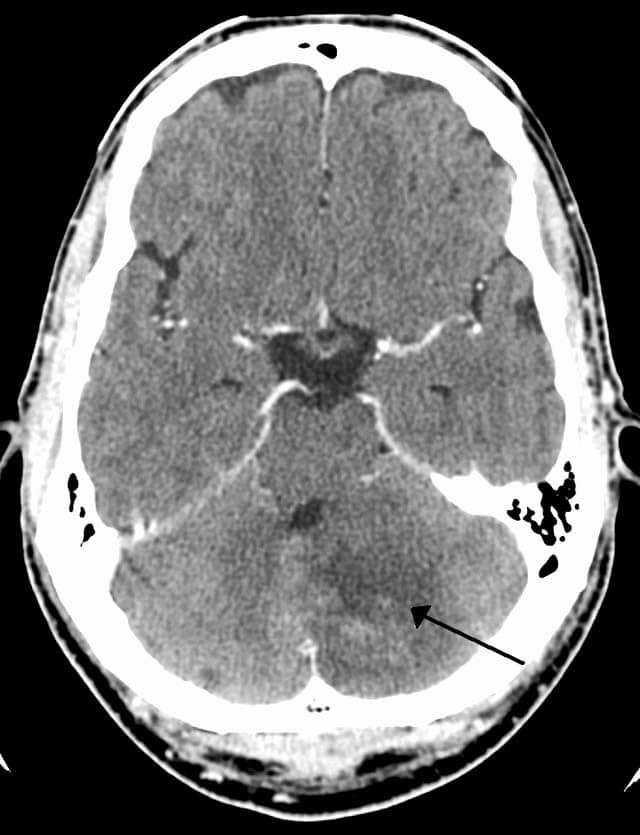

Dysfunction of the cerebellum can produce a wide range of symptoms and signs. The aetiology is varied; causes include stroke, physical trauma, tumours and chronic alcohol excess.

The clinical picture is dependent on the functional area of the cerebellum that is affected. Damage to the cerebrocerebellum and spinocerebellum presents with problems in carrying out skilled and planned movements and in motor learning.

A wide variety of manifestations are possible. These can be remembered using the acronym ‘DANISH‘:

- Dysdiadochokinesia (difficulty in carrying out rapid, alternating movements)

- Ataxia

- Nystagmus (coarse)

- Intention tremor

- Scanning speech

- Hypotonia

Damage to the vestibulocerebellum can manifest with loss of balance, abnormal gait with a wide stance.