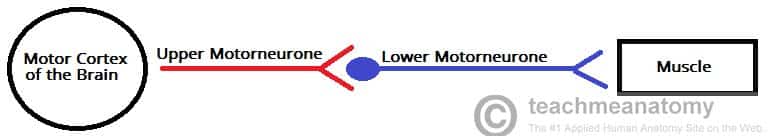

This article is about the descending tracts of the central nervous system. The descending tracts are the pathways by which motor signals are sent from the brain to lower motor neurones. The lower motor neurones then directly innervate muscles to produce movement.

The motor tracts can be functionally divided into two major groups:

- Pyramidal tracts – These tracts originate in the cerebral cortex, carrying motor fibres to the spinal cord and brain stem. They are responsible for the voluntary control of the musculature of the body and face.

- Extrapyramidal tracts – These tracts originate in the brain stem, carrying motor fibres to the spinal cord. They are responsible for the involuntary and automatic control of all musculature, such as muscle tone, balance, posture and locomotion

There are no synapses within the descending pathways. At the termination of the descending tracts, the neurones synapse with a lower motor neurone. Thus, all the neurones within the descending motor system are classed as upper motor neurones. Their cell bodies are found in the cerebral cortex or the brain stem, with their axons remaining within the CNS.

Fig 1 – Schematic of the motor nervous system. The descending tracts are represented by upper motor neurones.

Pyramidal Tracts

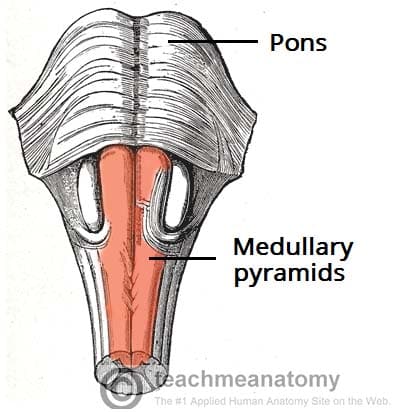

The pyramidal tracts derive their name from the medullary pyramids of the medulla oblongata, which they pass through.

These pathways are responsible for the voluntary control of the musculature of the body and face.

Functionally, these tracts can be subdivided into two:

- Corticospinal tracts – supplies the musculature of the body.

- Corticobulbar tracts – supplies the musculature of the head and neck.

We shall now discuss both pathways in further detail.

Corticospinal Tracts

The corticospinal tracts begin in the cerebral cortex, from which they receive a range of inputs:

- Primary motor cortex

- Premotor cortex

- Supplementary motor area

They also receive nerve fibres from the somatosensory area, which play a role in regulating the activity of the ascending tracts.

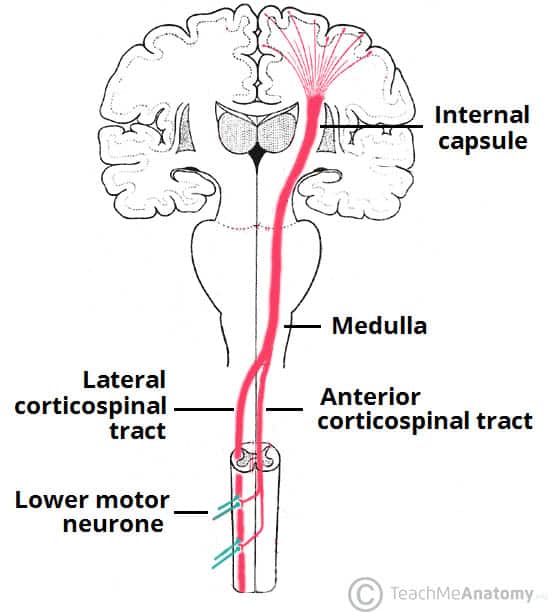

After originating from the cortex, the neurones converge, and descend through the internal capsule (a white matter pathway, located between the thalamus and the basal ganglia). This is clinically important, as the internal capsule is particularly susceptible to compression from haemorrhagic bleeds, known as a ‘capsular stroke‘. Such an event could cause a lesion of the descending tracts.

After the internal capsule, the neurones pass through the crus cerebri of the midbrain, the pons and into the medulla.

In the most inferior (caudal) part of the medulla, the tract divides into two:

The fibres within the lateral corticospinal tract decussate (cross over to the other side of the CNS). They then descend into the spinal cord, terminating in the ventral horn (at all segmental levels). From the ventral horn, the lower motor neurones go on to supply the muscles of the body.

The anterior corticospinal tract remains ipsilateral, descending into the spinal cord. They then decussate and terminate in the ventral horn of the cervical and upper thoracic segmental levels.

Fig 3 – The corticospinal tracts. Note the area of decussation of the lateral corticospinal tract in the medulla.

Corticobulbar Tracts

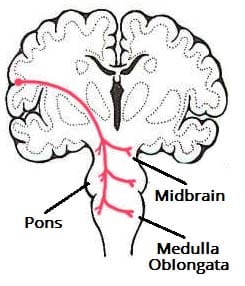

The corticobulbar tracts arise from the lateral aspect of the primary motor cortex. They receive the same inputs as the corticospinal tracts. The fibres converge and pass through the internal capsule to the brainstem.

The neurones terminate on the motor nuclei of the cranial nerves. Here, they synapse with lower motor neurones, which carry the motor signals to the muscles of the face and neck.

Clinically, it is important to understand the organisation of the corticobulbar fibres. Many of these fibres innervate the motor neurones bilaterally. For example, fibres from the left primary motor cortex act as upper motor neurones for the right and left trochlear nerves. There are a few exceptions to this rule:

- Upper motor neurones for the facial nerve (CN VII) have a contralateral innervation. This only affects the muscles in the lower quadrant of the face – below the eyes. (The reasons for this are beyond the scope of this article)

- Upper motor neurons for the hypoglossal (CN XII) nerve only provide contralateral innervation.

Fig 4 – Overview of the right corticobulbar tract. Note that this is a simplified diagram, ignoring the bilateral nature of these pathways.

Extrapyramidal Tracts

The extrapyramidal tracts originate in the brainstem, carrying motor fibres to the spinal cord. They are responsible for the involuntary and automatic control of all musculature, such as muscle tone, balance, posture and locomotion.

There are four tracts in total. The vestibulospinal and reticulospinal tracts do not decussate, providing ipsilateral innervation. The rubrospinal and tectospinal tracts do decussate, and therefore provide contralateral innervation

Vestibulospinal Tracts

There are two vestibulospinal pathways; medial and lateral. They arise from the vestibular nuclei, which receive input from the organs of balance. The tracts convey this balance information to the spinal cord, where it remains ipsilateral.

Fibres in this pathway control balance and posture by innervating the ‘anti-gravity’ muscles (flexors of the arm, and extensors of the leg), via lower motor neurones.

Reticulospinal Tracts

The two recticulospinal tracts have differing functions:

- The medial reticulospinal tract arises from the pons. It facilitates voluntary movements, and increases muscle tone.

- The lateral reticulospinal tract arises from the medulla. It inhibits voluntary movements, and reduces muscle tone.

Rubrospinal Tracts

The rubrospinal tract originates from the red nucleus, a midbrain structure. As the fibres emerge, they decussate (cross over to the other side of the CNS), and descend into the spinal cord. Thus, they have a contralateral innervation.

Its exact function is unclear, but it is thought to play a role in the fine control of hand movements

Tectospinal Tracts

This pathway begins at the superior colliculus of the midbrain. The superior colliculus is a structure that receives input from the optic nerves. The neurones then quickly decussate, and enter the spinal cord. They terminate at the cervical levels of the spinal cord.

The tectospinal tract coordinates movements of the head in relation to vision stimuli.

Clinical Relevance: Upper Motor Neurone Lesion

Upper motor neurone lesions are also known as supranuclear lesions.

Damage to the Corticospinal Tracts

The pyramidal tracts are susceptible to damage, because they extend almost the whole length of the central nervous system. As mentioned previously, they particularly vulnerable as they pass through the internal capsule – a common site of cerebrovascular accidents (CVA).

If there is only a unilateral lesion of the left or right corticospinal tract, symptoms will appear on the contralateral side of the body. The cardinal signs of an upper motor neurone lesion are:

- Hypertonia – an increased muscle tone

- Hyperreflexia – increased muscle reflexes

- Clonus – involuntary, rhythmic muscle contractions

- Babinski sign – extension of the hallux in response to blunt stimulation of the sole of the foot

- Muscle weakness

Damage to the Corticobulbar Tracts

Due to the bilateral nature of the majority of the corticobulbar tracts, a unilateral lesion usually results in mild muscle weakness. However, not all the cranial nerves receive bilateral input, and so there are a few exceptions:

- Hypoglossal nerve – a lesion to the upper motor neurones for CN XII will result in spastic paralysis of the contralateral genioglossus. This will result in the deviation of the tongue to the contralateral side.

- Note: this is in contrast to a lower motor neurone lesion, where the tongue deviates towards the damaged side.

- Facial nerve – a lesion to the upper motor neurones for CN VII will result in spastic paralysis of the muscles in the contralateral lower quadrant of the face.

Damage to the Extrapyramidal Tracts

Extrapyramidal tract lesions are commonly seen in degenerative diseases, encephalitis and tumours. They result in various types of dyskinesias or disorders of involuntary movement.