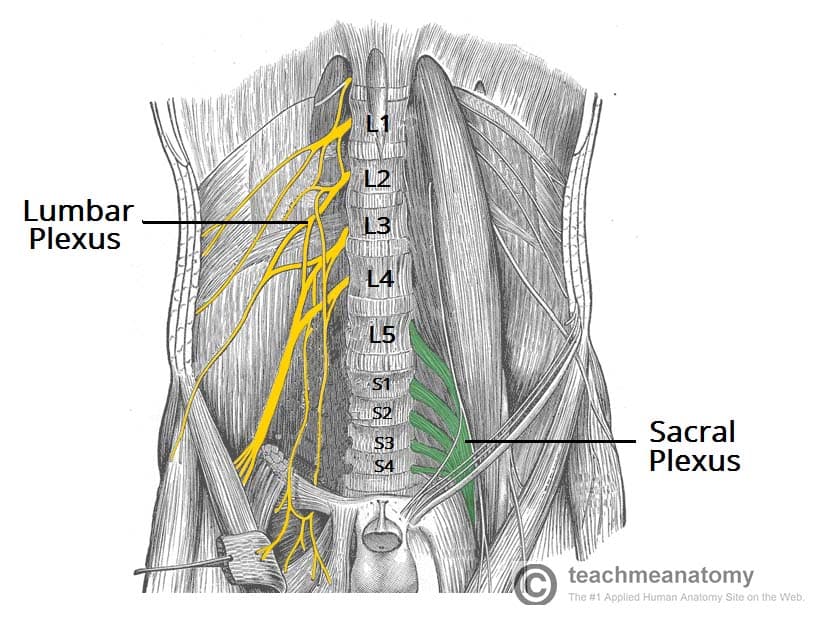

The lumbar plexus is a network of nerve fibres that supplies the skin and musculature of the lower limb. It is located in the lumbar region, within the substance of the psoas major muscle and anterior to the transverse processes of the lumbar vertebrae.

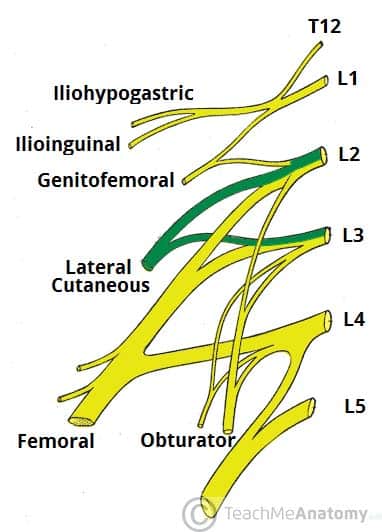

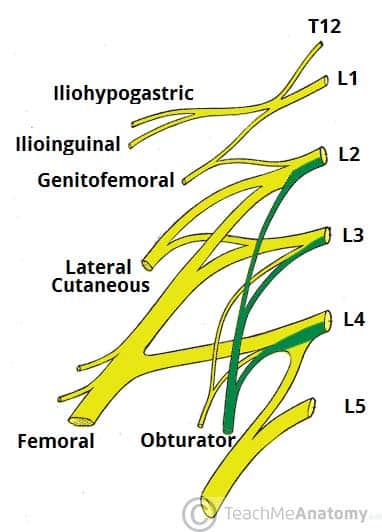

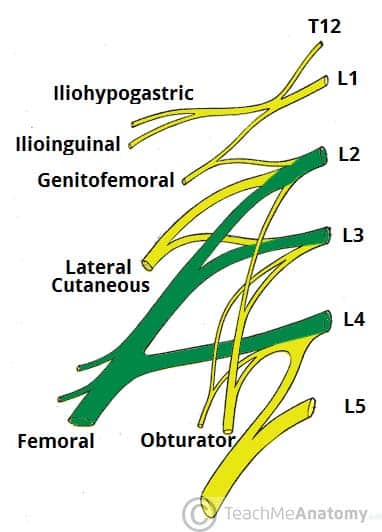

The plexus is formed by the anterior rami (divisions) of the lumbar spinal nerves L1, L2, L3 and L4. It also receives contributions from thoracic spinal nerve 12. In this article, we shall look at the anatomy of the lumbar plexus – its formation and major branches.

Spinal Nerves

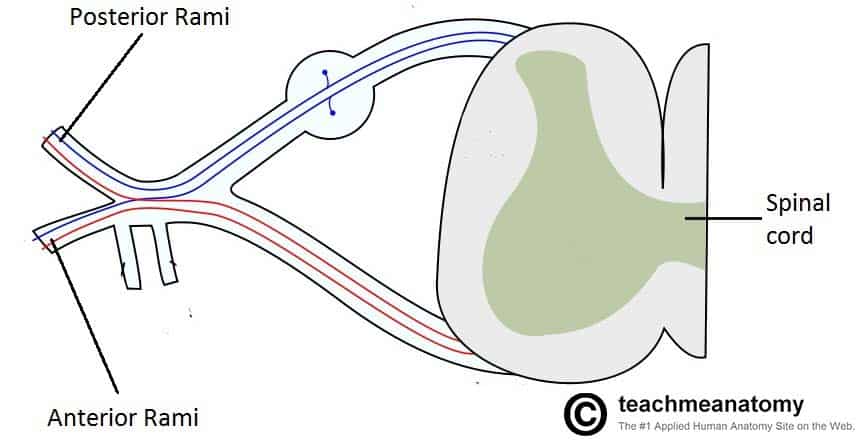

The spinal nerves L1 – L4 form the basis of the lumbar plexus. At each vertebral level, paired spinal nerves leave the spinal cord via the intervertebral foramina of the vertebral column. Each nerve then divides into anterior and posterior nerve fibres.

The lumbar plexus begins as the anterior fibres of the spinal nerves L1, L2, L3, and L4.

Fig 1 – The spinal cord outflow at each vertebral level. The anterior rami of vertebral levels L1-L4 make up the roots of the lumbar plexus

The Branches

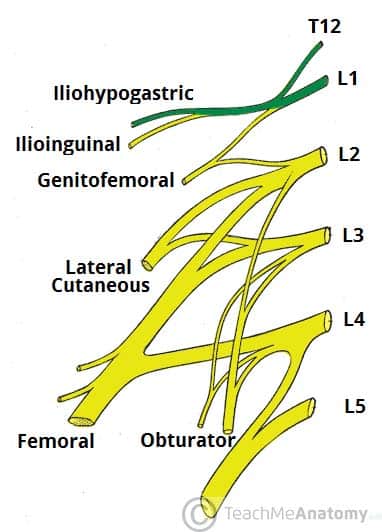

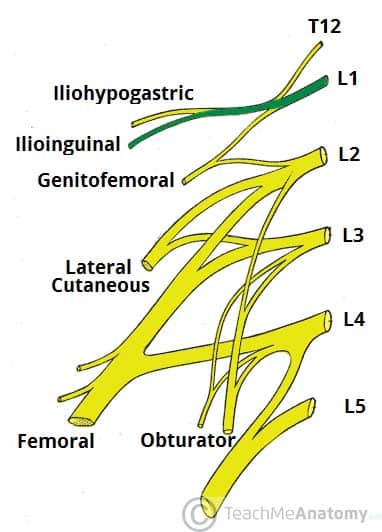

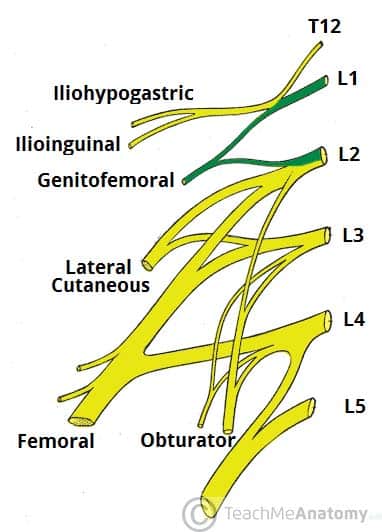

The anterior rami of the L1-L4 spinal roots divide into several cords. These cords then combine together to form the six major peripheral nerves of the lumbar plexus. These nerves then descend down the posterior abdominal wall to reach the lower limb, where they innervate their target structures.

We shall now consider the branches of the lumbar plexus. (Note: In this article we shall include only brief notes on the function of these nerves – for more detailed information click on the title to visit their respective pages)

Iliohypogastric Nerve

The iliohypogastric nerve is the first major branch of the lumbar plexus. It runs to the iliac crest, across the quadratus lumborum muscle of the posterior abdominal wall. It then perforates the transversus abdominis, and divides into its terminal branches.

Roots: L1 (with contributions from T12).

Motor Functions: Innervates the internal oblique and transversus abdominis.

Sensory Functions: Innervates the posterolateral gluteal skin in the pubic region. (Tip: an easy way to remember that the IlioHypogastric comes before the IlioInguinal is that H comes before I in the alphabet!)

Ilioinguinal Nerve

The ilioinguinal nerve follows the same anatomical course as the larger iliohypogastric nerve. After innervating the muscles of the anterior abdominal wall, it passes through the superficial inguinal ring to innervate the skin of the genitalia and middle thigh.

Roots: L1.

Motor Functions: Innervates the internal oblique and transversus abdominis.

Sensory Functions: Innervates the skin on the superior antero-medial thigh. In males, it also supplies the skin over the root of the penis and anterior scrotum. In females, it supplies the skin over mons pubis and labia majora.

Genitofemoral Nerve

After leaving the psoas major muscle, the genitofemoral nerve quickly divides into a genital branch, and a femoral branch.

Roots: L1, L2.

Motor Functions: The genital branch innervates the cremasteric muscle.

Sensory Functions: The genital branch innervates the skin of the anterior scrotum (in males) or the skin over mons pubis and labia majora (in females). The femoral branch innervates the skin on the upper anterior thigh.

Lateral Cutaneous Nerve of the Thigh

This nerve has a purely sensory function. It enters the thigh at the lateral aspect of the inguinal ligament, where it provides cutaneous innervation to the skin there.

Roots: L2, L3

Motor Functions: None.

Sensory Functions: Innervates the anterior and lateral thigh down to the level of the knee.

Obturator Nerve

See more detailed information here

Roots: L2, L3, L4.

Motor Functions: Innervates the muscles of the medial thigh – the obturator externus, adductor longus, adductor brevis, adductor magnus and gracilis.

Sensory Functions: Innervates the skin over the medial thigh.

Femoral Nerve

See more detailed information here.

Roots: L2, L3, L4.

Motor Functions: Innervates the muscles of the anterior thigh – the illiacus, pectineus, sartorius and quadriceps femoris.

Sensory Functions: Innervates the skin on the anterior thigh and the medial leg.

Note: A useful memory aid for the branches of the lumbar plexus is: I, I Get Leftovers On Fridays. This stands for the Iliohypogastric, Ilioinguinal, Genitofemoral, Lateral cutaneous nerve of the thigh, Obturator and Femoral.

Clinical Relevance – Lumbosacral Plexopathy

A lumbosacral plexopathy is a disorder affecting either the lumbar or sacral plexus. They are rare syndromes, caused by damage to the nerve bundles.

A plexopathy is suspected if the symptoms cannot be localised to a single nerve. Patients may complain of neuropathic pains, numbness or weakness and wasting of muscles.

One of the main causes of lumbosacral plexopathy is diabetic amyotrophy, also known as lumbosacral radioplexus neurophagy. In this condition, the high blood sugar levels damage the nerves. Idiopathic plexopathy is another cause, being the lumbosacral equivalent of Parsonage-Turner syndrome (which affects the brachial plexus). Tumours and other local invasions can cause the plexopathy due to the compression of the plexus.

Treatment depends on what is causing the symptoms. For tumours and space-occupying lesions, they should be removed if possible. For diabetic and idiopathic causes, treatment with high-dose corticosteroids can be useful.