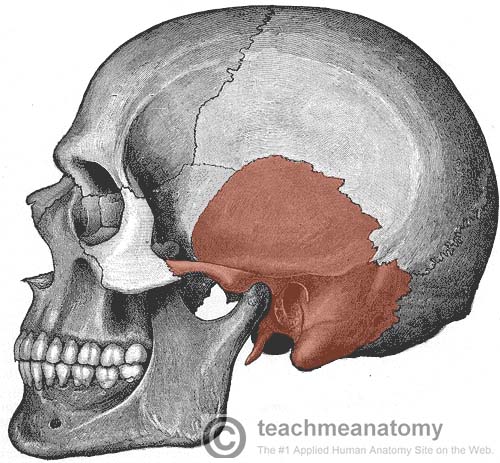

The temporal bone contributes to the lower lateral walls of the skull.

It contains the middle and inner portions of the ear, and is crossed by the majority of the cranial nerves. The lower portion of the bone articulates with the mandible, forming the temporomandibular joint of the jaw.

In this article, we shall look at the anatomy of the temporal bone – its component parts, articulations, and clinical correlations.

Fig 1 – Lateral view of the skull. The temporal bone has been highlighted.

Anatomical Structure

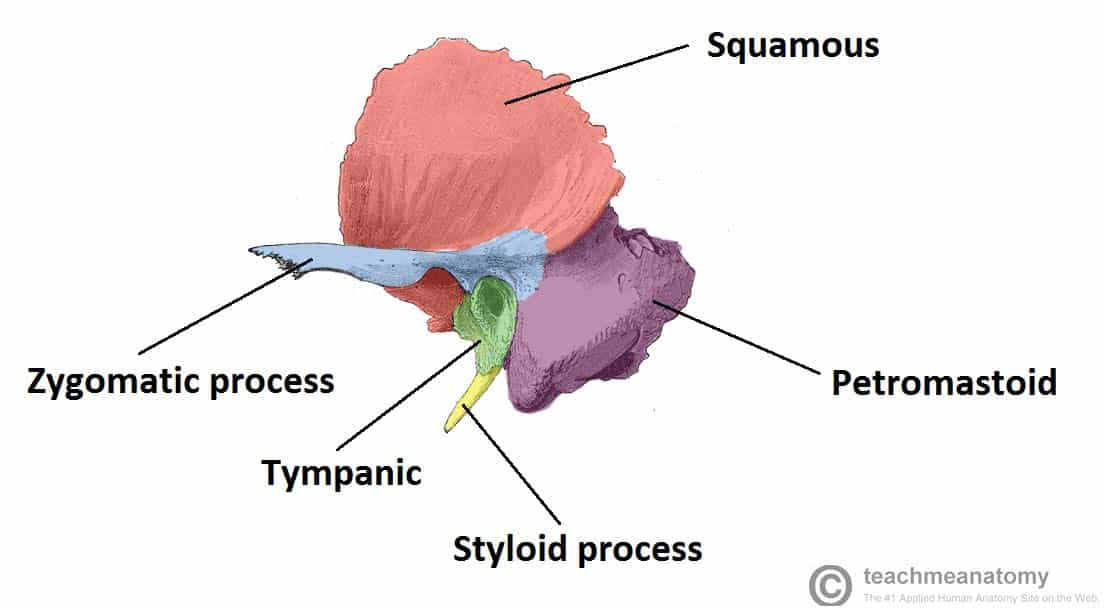

The temporal bone itself is comprised of five constituent parts. The squamous, tympanic and petromastoid parts make up the majority of the bone, with the zygomatic and styloid processes projecting outwards.

We shall now examine the constituent parts of the temporal bone in more detail.

Squamous

Also known as the squama temporalis, this is the largest part of the temporal bone. It is flat and plate-like, located superiorly. The outer facing surface of the squamous bone is convex in shape, forming part of the temporal fossa.

The lower part of the squamous bone is the site of origin of the temporalis muscle

The bone articulates with the sphenoid bone anteriorly, and parietal bone laterally.

Zygomatic Process

The zygomatic process arises from the lower part of the squama temporalis. It projects anteriorly, articulating with the temporal process of the zygomatic bone. These two structures form the zygomatic arch (palpable as ‘cheek bones’).

One of the zygomatic processes’ attachments to the temporal bone forms the articular tubercle – the anterior boundary of the mandibular fossa, part of the temporomandibular joint

The masseter muscles attaches some fibres to the lateral surface of the zygomatic process.

Tympanic

The tympanic part of the temporal bone lies inferiorly to the squamous, and anteriorly to the petromastoid part.

It surrounds the external auditory opening, which leads into the external auditory meatus of the external ear.

Styloid Process

The styloid process located immediately underneath the opening to the auditory meatus. It acts as an attachment point for muscles and ligaments, such as the stylomandibular ligament of the TMJ.

Petromastoid

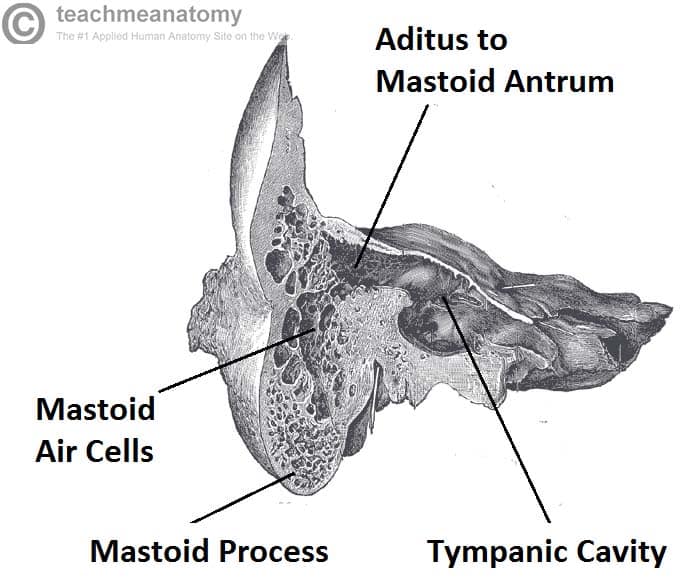

This portion of the temporal bone is located posteriorly. It can be split into a mastoid and petrous parts.

There are two items of note on the mastoid. The first is the mastoid process, an inferior projection of bone, palpable just behind the ear. It is a site of attachment for many muscles, such as the sternocleidomastoid.

Also of clinical importance are the mastoid air cells. These are hollowed out areas within the temporal bone. They act as a reservoir of air, equalising the pressure within the middle ear in the case of auditory tube dysfunction. The mastoid air cells can also become infected, known as mastoiditis.

The petrous part is pyramidal shaped, and lies at the base of temporal bone. It contains the inner ear.

Fig 2 – Coronal section of temporal bone, showing the mastoid air cells in more detail

Muscular Attachments

The temporal bone serves as a point of attachment for many muscles. Due to the involvement of the temporal bone in forming the temporomandibular joint (i.e. joint of the jaw) some fibres from muscles of mastication such as the temporalis and masseter muscles attach to the temporal bone. In addition to this the mastoid process of the temporal bone is a major site of muscle attachment. Some key muscular attachments are outlined in the table below.

| Muscle | Site of Attachment | Description |

| Temporalis | Originates from the lower part of squamous | Muscle of mastication |

| Masseter | Lateral zygomatic surface | Muscle of mastication |

| Sternocleidomastoid | Mastoid process | Superficial muscle of the neck. Involved in rotation of head and flexion of neck. Important landmark for the anterior and posterior cervical triangles. |

| Posterior belly of digastric | Mastoid process | A suprahyoid muscle. Involved in processes such as swallowing. |

| Splenius capitis | Mastoid process | Strap-like muscle in the back of the neck. Involved in movements such as shaking the head. |

Articulations

A major articulation of the temporal bone is with the mandible (i.e. jaw bone) to form the temporomandibular joint which is covered in detail here.

The squamous part of the temporal bone also articulates with the sphenoid bone anteriorly and the parietal bone laterally.

The zygomatic process of the temporal bone also articulates with the zygomatic bone to form the zygomatic arch (i.e. cheekbones).

Clinical Relevance: Mastoiditis

Middle ear infections (otitis media) can spread to the mastoid air cells. Due to their porous nature, they are a suitable site for pathogenic replication.

The mastoid process itself can get infected, and this can spread to the middle cranial fossa, and into the brain, causing meningitis.

If mastoiditis is suspected, the pus must be drained from the air cells. When doing so, care must be taken not the damage the nearby facial nerve.

Clinical Relevance: Temporal Bone Fractures

The temporal bone is relatively strong, and thus it is usually only fractured as a result of blunt trauma to the skull.

It has a varied presentation. Ear-related disorders are commonly seen, such as vertigo or hearing loss. As the facial nerve travels through the temporal bone, it can be damaged, with paralysis resulting. Other symptoms include bleeding from the ear and bruising around the mastoid process.

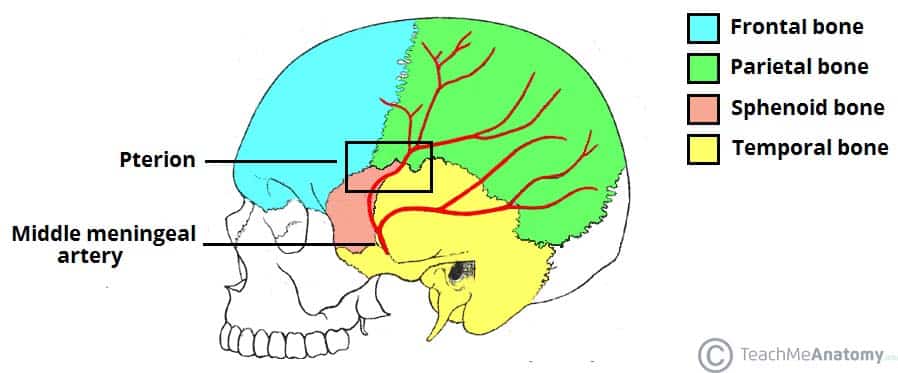

Clinical Relevance: Fractures of the Pterion

Where the temporal, parietal, frontal and sphenoid bones meet, the skull is at its weakest, and susceptible to fracture. This point is known as the pterion.

The middle meningeal artery (MMA) supplies the skull and the dura mater (the outer membranous layer covering the brain). It travels underneath the pterion, thus a fracture of the skull at the pterion can injure or completely lacerate the MMA.

Blood will then collect in between the dura mater and the skull, causing a dangerous increase in intra-cranial pressure. This is known as an extradural haematoma.

The increase in intracranial pressure causes a variety of symptoms; nausea, vomiting, seizures, bradycardia and limb weakness. It is treated by diuretics in minor cases, but surgical intervention is required in cases of major haemorrhage.

Fig 3 – Lateral view of the skull, showing the path of the meningeal arteries. Note the pterion, a weak point of the skull, where the anterior middle meningeal artery is at risk of damage.