The skull is a bony structure that supports the face and forms a protective cavity for the brain. It is comprised of many bones, which are formed by intramembranous ossification, and joined by sutures (fibrous joints).

The bones of the skull can be considered as two groups: those of the cranium (which consist of the cranial roof and cranial base) and those of the face.

In this article, we shall look at the anatomy of the bones of the skull – their orientation, articulations, and clinical relevance.

Cranium

The cranium (also known as the neurocranium) is formed by the superior aspect of the skull. It encloses and protects the brain, meninges, and cerebral vasculature.

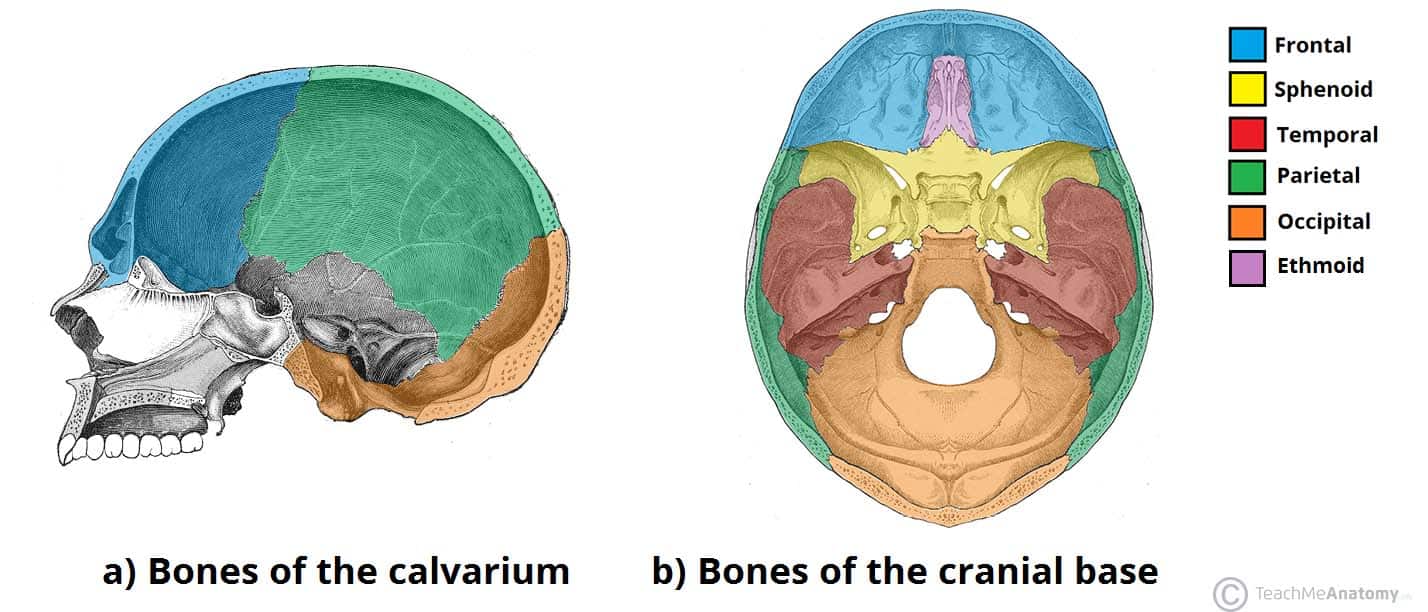

Anatomically, the cranium can be subdivided into a roof and a base:

- Cranial roof – comprised of the frontal, occipital and two parietal bones. It is also known as the calvarium.

- Cranial base – comprised of the frontal, sphenoid, ethmoid, occipital, parietal, and temporal bones. These bones articulate with the 1st cervical vertebra (atlas), the facial bones, and the mandible (jaw).

Clinical Relevance: Cranial Fractures

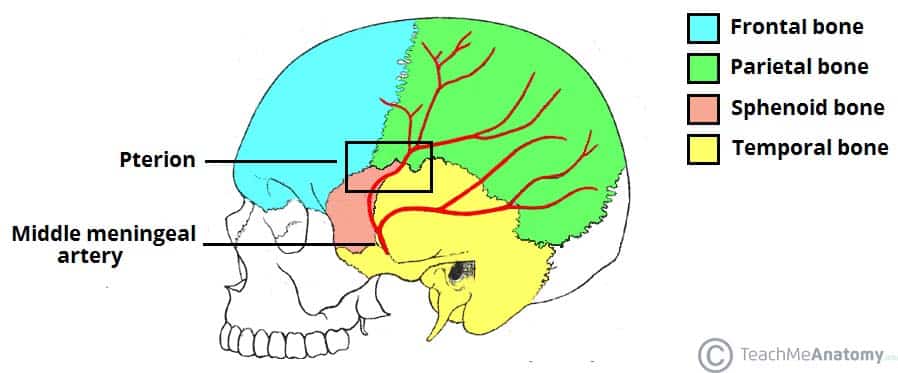

Fractures of the cranium typically arise from blunt force or penetrating trauma. When considering cranial fractures, one area of clinical importance is the pterion – a H-shaped junction between the temporal, parietal, frontal, and sphenoid bones.

The pterion overlies the middle meningeal artery, and fractures in this area may injury the vessel. Blood can accumulate between the skull and the dura mater, forming an extradural haematoma.

Fig 2 – Lateral view of the skull, showing the path of the meningeal arteries. Note the pterion, a weak point of the skull, where the anterior middle meningeal artery is at risk of damage.

Face

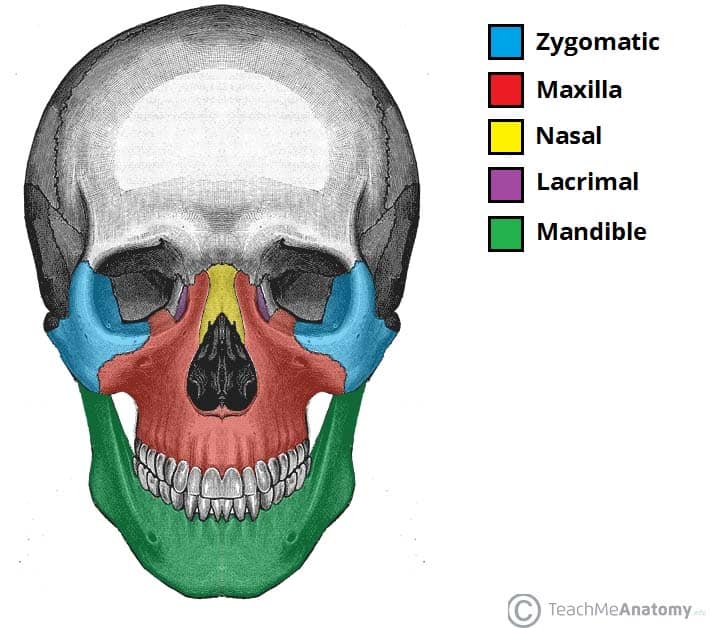

The facial skeleton (also known as the viscerocranium) supports the soft tissues of the face.

It consists of 14 bones, which fuse to house the orbits of the eyes, the nasal and oral cavities, and the sinuses. The frontal bone, typically a bone of the calvaria, is sometimes included as part of the facial skeleton.

The facial bones are:

- Zygomatic (2) – forms the cheek bones of the face and articulates with the frontal, sphenoid, temporal and maxilla bones.

- Lacrimal (2) – the smallest bones of the face. They form part of the medial wall of the orbit.

- Nasal (2) – two slender bones that are located at the bridge of the nose.

- Inferior nasal conchae (2) – located within the nasal cavity, these bones increase the surface area of the nasal cavity, thus increasing the amount of inspired air that can come into contact with the cavity walls.

- Palatine (2) – situated at the rear of oral cavity and forms part of the hard palate.

- Maxilla (2) – comprises part of the upper jaw and hard palate.

- Vomer – forms the posterior aspect of the nasal septum.

- Mandible (jaw) – articulates with the base of the cranium at the temporomandibular joint (TMJ).

Fig 3 – Anterior view of the face, showing some of the bones of the nasal skeleton. The vomer, palatine and inferior conchae bones lie deep within the face.

Clinical Relevance: Facial Fractures

Fractures of the facial skeleton are relatively common and most frequently result from road traffic collisions, fist fights, and falls.

The four most common facial fracture types are:

- Nasal fracture – the most common facial fracture, due to the prominent position of the nasal bones at the bridge of the nose. There is often significant soft tissue swelling and associated epistaxis.

- Maxillary fracture – associated with high-energy trauma. Fractures affecting of maxillary bones are classified using the Le Fort classification, ranging from 1 to 3.

- Mandibular fracture – often bilateral occurring directly at the side of trauma, and indirectly at the contralateral side due to transmitted forces. Clinical features include pain at fracture site and misalignment of the teeth (malocclusion)

- Zygomatic arch fracture – associated with trauma to the side of the face. Displaced fractures can damage the nearby infraorbital nerve, leading to ipsilateral paraesthesia of the check, nose, and lip.

Sutures of the Skull

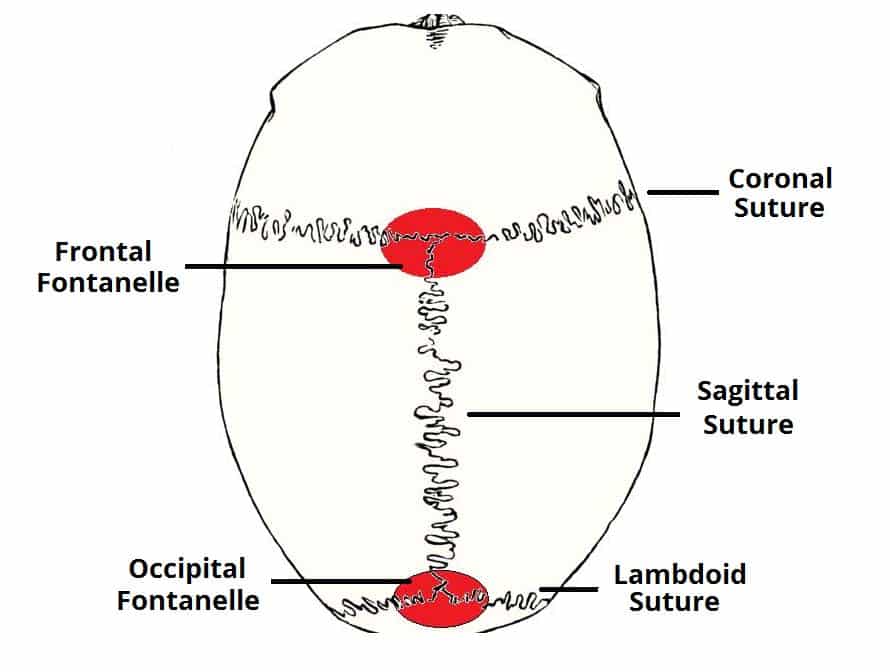

Sutures are a type of fibrous joint that are unique to the skull. They are immovable and fuse completely around the age of 20.

These joints are important in the context of trauma, as they represent points of potential weakness in the skull. The main sutures in the adult skull are:

- Coronal suture – fuses the frontal bone with the two parietal bones.

- Sagittal suture – fuses both parietal bones to each other.

- Lambdoid suture – fuses the occipital bone to the two parietal bones.

In neonates, the incompletely fused suture joints give rise to membranous gaps between the bones, known as fontanelles. The two major fontanelles are:

- Frontal fontanelle – located at the junction of the coronal and sagittal sutures

- Occipital fontanelle – located at the junction of the sagittal and lambdoid sutures