The temporomandibular joint (TMJ) is formed by the articulation of the mandible and the temporal bone of the cranium. It is located anteriorly to the tragus of the ear, on the lateral aspect of the face.

In this article, we shall look at the anatomy of the temporomandibular joint – its articulating surfaces, ligaments and clinical correlations.

Articulating Surfaces

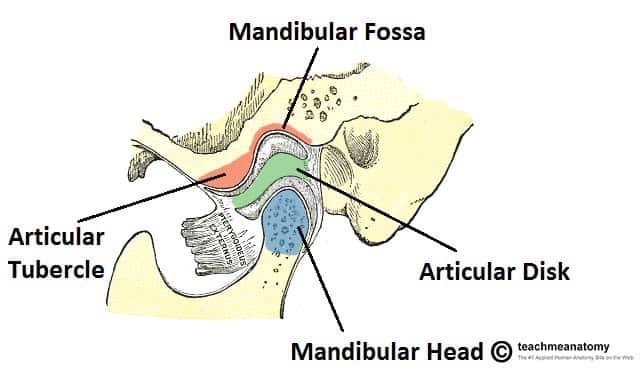

The temporomandibular joint consists of articulations between three surfaces; the mandibular fossa and articular tubercle (from the squamous part of the temporal bone), and the head of mandible.

This joint has a unique mechanism; the articular surfaces of the bones never come into contact with each other – they are separated by an articular disk. The presence of such a disk splits the joint into two synovial joint cavities, each lined by a synovial membrane. The articular surface of the bones are covered by fibrocartilage, not hyaline cartilage.

Ligaments

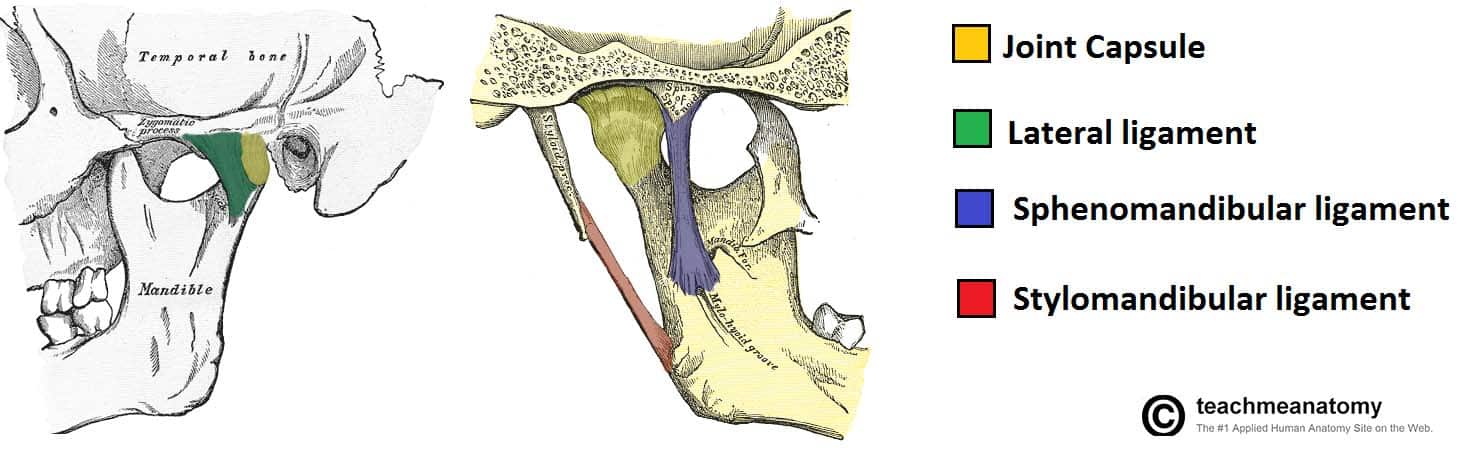

There are three extracapsular ligaments. They act to stabilise the temporomandibular joint.

- Lateral ligament – runs from the beginning of the articular tubule to the mandibular neck. It is a thickening of the joint capsule, and acts to prevent posterior dislocation of the joint.

- Sphenomandibular ligament – originates from the sphenoid spine, and attaches to the mandible.

- Stylomandibular ligament – a thickening of the fascia of the parotid gland. Along with the facial muscles, it supports the weight of the jaw.

Fig 2 – The joint capsule and accessory ligaments of the temporomandibular joint.

Movements

Movements at this joint are produced by the muscles of mastication, and the hyoid muscles. The two divisions of the temporomandibular joint have different functions.

Protrusion and Retraction

The upper part of the joint allows protrusion and retraction of the mandible – the anterior and posterior movements of the jaw.

The lateral pterygoid muscle is responsible for protrusion (assisted by the medial pterygoid), and the posterior fibres of the temporalis perform retraction. A lateral movement (i.e. for chewing and grinding) is achieved by alternately protruding and retracting the mandible on each side.

Elevation and Depression

The lower part of the joint permits elevation and depression of the mandible; opening and closing the mouth. Depression is mostly caused by gravity. However, if there is resistance, the digastric, geniohyoid, and mylohyoid muscles assist. Elevation is very strong movement, caused by the contraction of the temporalis, masseter, and medial pterygoid muscles.

Neurovascular supply

The arterial supply to the TMJ is provided by the branches of the external carotid, principally the superficial temporal branch. Other contributing branches include the deep auricular, ascending pharyngeal and maxillary arteries.

The TMJ is innervated by the auriculotemporal and masseteric branches of the mandibular nerve (CN V3).

Clinical Relevance: Temporomandibular Joint Dislocation

A dislocation of the temporomandibular joint can occur via a blow to the side of the face, yawning, or taking a large bite. The head of the mandible ‘slips’ out of the mandibular fossa, and is pulled anteriorly.

The patient becomes unable to close their mouth. The facial and auriculotemporal nerves run close to the joint, and can be damaged if the injury is high-energy.

Posterior dislocations of the TMJ are possible, but very rare, requiring a large amount of force to overcome the postglenoid tubercle and strong intrinsic lateral ligament.