The spleen is an organ located in the upper left abdomen, and is roughly the size of a clenched fist. In the adult, the spleen functions mainly as a blood filter, removing old red blood cells. It also plays a role in both cell-mediated and humoral immune responses.

In this article, we shall look at the anatomy of the spleen – its anatomical position, structure and vasculature.

Anatomical Position

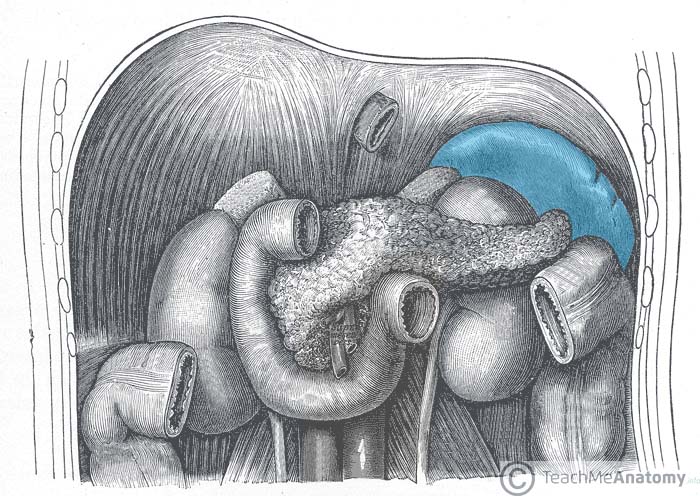

The spleen is located in the upper left quadrant of the abdomen, under cover of the diaphragm and the ribcage – and therefore cannot normally be palpated on clinical examination (except when enlarged). It is an intraperitoneal organ, entirely surrounded by peritoneum (except at the splenic hilum).

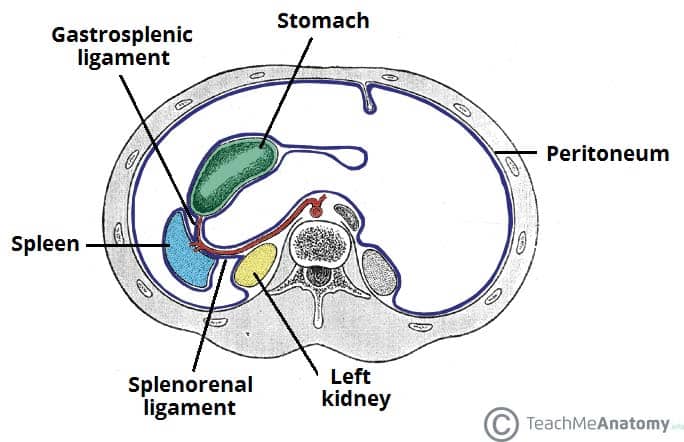

The spleen is connected to the stomach and kidney by parts of the greater omentum – a double fold of peritoneum that originates from the stomach:

- Gastrosplenic ligament – anterior to the splenic hilum, connects the spleen to the greater curvature of the stomach.

- Splenorenal ligament – posterior to the splenic hilum, connects the hilum of the spleen to the left kidney. The splenic vessels and tail of the pancreas lie within this ligament

Between these two ligaments is the lesser sac.

Fig 2 – The ligaments of the spleen. Note how the splenic vessels run within the splenorenal ligament.

Structure

The spleen has a slightly oval shape. It is covered by a weak capsule that protects the organ whilst allowing it to expand in size.

The outer surface of the spleen can be anatomically divided into two:

- Diaphragmatic surface – in contact with diaphragm and ribcage.

- Visceral surface – in contact with the other abdominal viscera.

It has anterior, superior, posteromedial and inferior borders. The posteromedial and inferior borders are smooth, whilst the anterior and superior borders contain notches.

In enlargement of the spleen (known as splenomegaly), the superior border moves inferomedially, and its notches can be palpated.

Vasculature

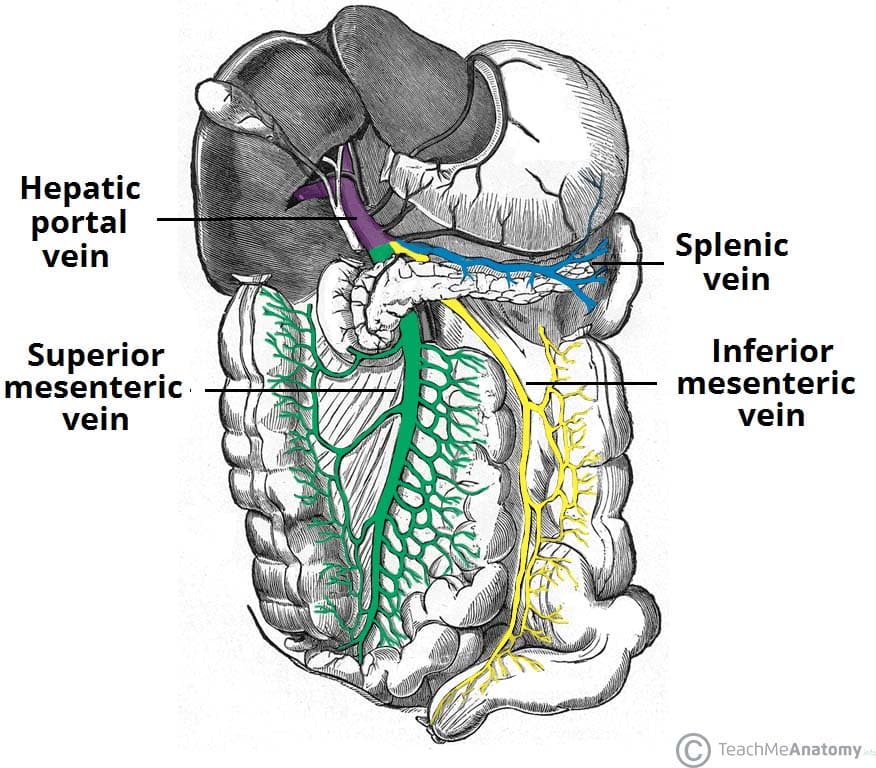

The spleen is a highly vascular organ. It receives most of its arterial supply from the splenic artery. This vessel arises from the coeliac trunk, running laterally along the superior aspect of the pancreas, within the splenorenal ligament. As the artery reaches the spleen, it branches into five vessels – each supplying a different part of the organ.

These arterial branches do not anastomose with each other – giving rise to vascular segments of the spleen. This enables a surgeon to remove one of these segments without affecting the others (a procedure known as a subtotal splenectomy).

Venous drainage occurs through the splenic vein. It combines with the superior mesenteric vein to form the hepatic portal vein.

Fig 3 – An overview of the venous portal system – draining into the hepatic portal vein.

Innervation

The nerve supply to the spleen is from the coeliac plexus.

Lymphatics

The lymphatic vessels of the spleen follow the splenic vessels mentioned above and drain into the pancreaticosplenic lymph nodes, and ultimately the coeliac nodes.

Clinical Relevance: Rupture of the Spleen

The spleen is the abdominal organ with the highest incidence of injury. A splenic rupture occurs when there is a break in its fibroelastic capsule, disrupting the underlying parenchyma.

Rupture is caused by blunt or penetrating trauma. It is often associated with left rib fractures, with a bony fragment easily tearing the capsule.

As the spleen is a highly vascular organ, its rupture results in profuse bleeding into the peritoneal cavity. Splenectomy is indicated where injury to the spleen and subsequent haemorrhage are life threatening. This may be done as a sub-total (partial) splenectomy – recall that there are no arterial anastomoses in the spleen – or as a total splenectomy.

The liver and bone marrow take over some of the functions of the spleen, however, an individual who has no spleen is more susceptible to some bacterial infections and as such, requires life long antibiotics.

Further indications for splenectomy include haematological conditions such as haemolytic anaemia, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, hypersplenism and prolieferative disorders such as myelofibrosis of lymphoma.