The stomach, is an intraperitoneal digestive organ located between the oesophagus and the duodenum.

It has a ‘J’ shape, and features a lesser and greater curvature. The anterior and posterior surfaces are smoothly rounded with a peritoneal covering.

In this article, we shall look at the anatomy of the stomach – its position, structure and neurovascular supply.

Anatomical Position

The stomach lies within the superior aspect of the abdomen.

It primarily lies in the epigastric and umbilical regions, however, the exact size, shape and position of the stomach can vary from person to person and with position and respiration.

Anatomical Structure

Divisions of the Stomach

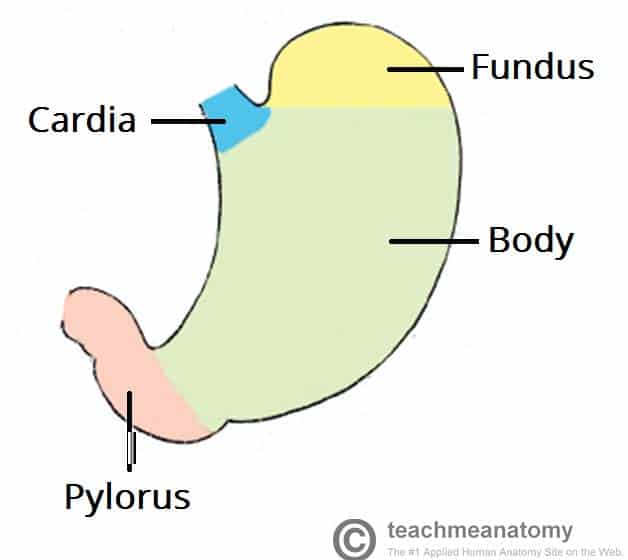

The stomach has four main anatomical divisions; the cardia, fundus, body and pylorus:

- Cardia – surrounds the superior opening of the stomach at the T11 level.

- Fundus – the rounded, often gas filled portion superior to and left of the cardia.

- Body – the large central portion inferior to the fundus.

- Pylorus – This area connects the stomach to the duodenum. It is divided into the pyloric antrum, pyloric canal and pyloric sphincter. The pyloric sphincter demarcates the transpyloric plane at the level of L1.

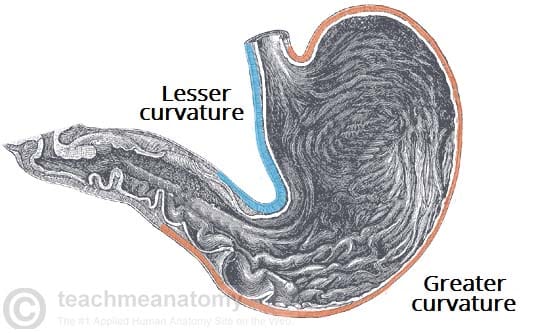

Greater and Lesser Curvatures

The medial and lateral borders of the stomach are curved, forming the lesser and greater curvatures:

- Greater curvature – forms the long, convex, lateral border of the stomach.

- Arising at the cardiac notch, it arches backwards and passes inferiorly to the left.

- It curves to the right as it continues medially to reach the pyloric antrum.

- The short gastric arteries and the right and left gastro-omental arteries supply branches to the greater curvature.

- Lesser curvature – forms the shorter, concave, medial surface of the stomach.

- The most inferior part of the lesser curvature, the angular notch, indicates the junction of the body and pyloric region.

- The lesser curvature gives attachment to the hepatogastric ligament and is supplied by the left gastric artery and right gastric branch of the hepatic artery.

Anatomical Relations

The anatomical relations of the stomach are given in the table below:

| Anatomical Relation | Structures |

| Superior | Oesophagus and left dome of the diaphragm |

| Anterior | Diaphragm, greater omentum, anterior abdominal wall, left lobe of liver, gall bladder |

| Posterior | Lesser sac, pancreas, left kidney, left adrenal gland, spleen, splenic artery, transverse mesocolon |

Sphincters of the Stomach

There are two sphincters of the stomach, located at each orifice. They control the passage of material entering and exiting the stomach.

Inferior Oesophageal Sphincter

The oesophagus passes through the diaphragm through the oesophageal hiatus at the level of T10. It descends a short distance to the inferior oesophageal sphincter at the T11 level which marks the transition point between the oesophagus and stomach (in contrast to the superior oesophageal sphincter, located in the pharynx). It allows food to pass through the cardiac orifice and into the stomach and is not under voluntary control.

Pyloric Sphincter

The pyloric sphincter lies between the pylorus and the first part of the duodenum. It controls of the exit of chyme (food and gastric acid mixture) from the stomach.

In contrast to the inferior oesophageal sphincter, this is an anatomical sphincter. It contains smooth muscle, which constricts to limit the discharge of stomach contents through the orifice.

Emptying of the stomach occurs intermittently when intragastric pressure overcomes the resistance of the pylorus. The pylorus is normally contracted so that the orifice is small and food can stay in the stomach for a suitable period. Gastric peristalsis pushes the chyme through the pyloric canal into the duodenum for further digestion.

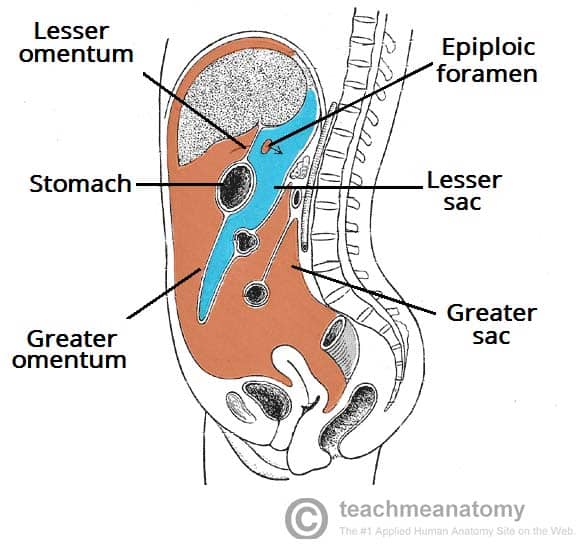

Greater and Lesser Omenta

Within the abdominal cavity, a double layered membrane called the peritoneum. supports most of the abdominal viscera and assists with their attachment to the abdominal wall.

The greater and lesser omenta are two structures that consist of peritoneum folded over itself (two layers of peritoneum – four membrane layers). Both omenta attach to the stomach, and are useful anatomical landmarks:

- Greater omentum – hangs down from the greater curvature of the stomach and folds back upon itself where it attaches to the transverse colon It contains many lymph nodes and may adhere to inflamed areas , therefore playing a key role in gastrointestinal immunity and minimising the spread of intraperitoneal infections.

- Lesser omentum– continuous with peritoneal layers of the stomach and duodenum, this smaller peritoneal fold arises at the lesser curvature and ascend to attach to the liver. The main function of the lesser omentum is to attach the stomach and duodenum to the liver.

Together, the greater and lesser omenta divide the abdominal cavity into two; the greater and lesser sac. The stomach lies immediately anterior to the lesser sac. The greater and lesser sacs communicate via the epiploic foramen, a hole in the lesser omentum.

Neurovascular Supply

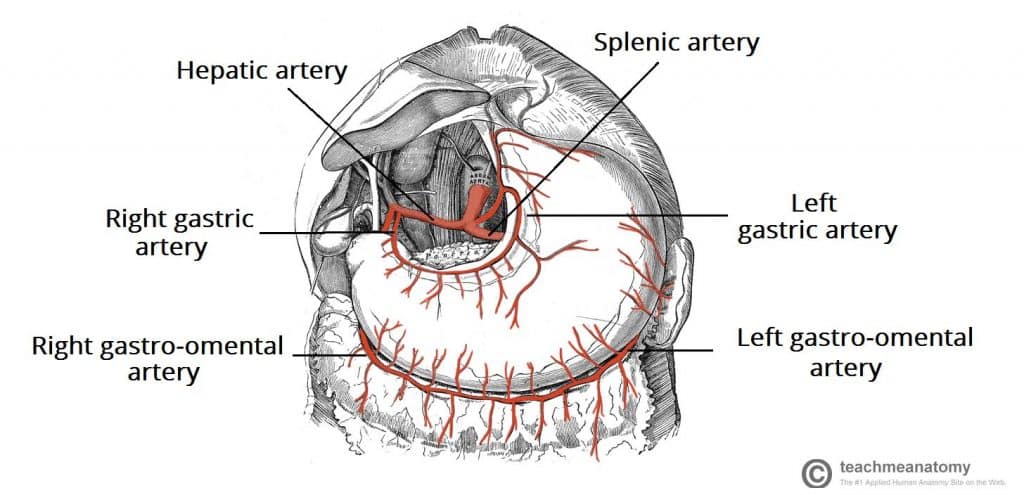

The arterial supply to the stomach comes from the celiac trunk and its branches. Anastomoses form along the lesser curvature by the right and left gastric arteries and along the greater curvature by the right and left gastro-omental arteries:

- Right gastric – branch of the proper hepatic artery, which arises from the common hepatic artery.

- Left gastric – arises directly from the coeliac trunk.

- Right gastro-omental – terminal branch of the gastroduodenal artery, which arises from the common hepatic artery.

- Left gastro-omental – branch of the splenic artery, which arises from the coeliac trunk.

The veins of the stomach run parallel to the arteries. The right and left gastric veins drain into the hepatic portal vein. The short gastric vein, left and right gastro-omental veins ultimately drain into the superior mesenteric vein.

Innervation

The stomach receives innervation from the autonomic nervous system:

- Parasympathetic nerve supply arises from the anterior and posterior vagal trunks, derived from the vagus nerve.

- Sympathetic nerve supply arises from the T6-T9 spinal cord segments and passes to the coeliac plexus via the greater splanchnic nerve. It also carries some pain transmitting fibres.

Lymphatics

The gastric lymphatic vessels travel with the arteries along the greater and lesser curvatures of the stomach. Lymph fluid drains into the gastric and gastro-omental lymph nodes found at the curvatures.

Efferent lymphatic vessels from these nodes connect to the coeliac lymph nodes, located on the posterior abdominal wall.

Clinical Relevance: Disorders of the Stomach

Gastro-Oesophageal Reflux Disease

This is a digestive disorder affecting the lower oesophageal sphincter. It refers to the movement of gastric acid and food into the oesophagus.

GORD is a common condition, affecting 5-7% of the population. Symptoms include dyspepsia, dysphagia, and an unpleasant sour taste in the mouth.

There are three main causes of reflux disease:

- Dysfunction of the lower oesophageal sphincter

- Delayed gastric emptying

- Hiatal hernia (see below)

Treatment involves lifestyle changes, medication such as a PPI to reduce stomach acid, and as a last resort, surgery.

Hiatus Hernia

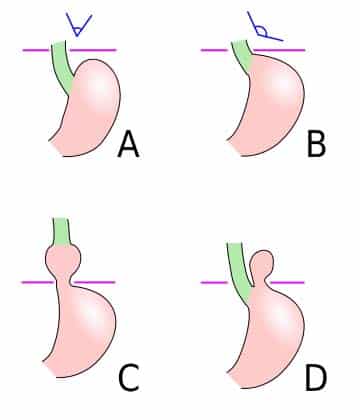

A hiatus hernia occurs when a part of the stomach protrudes into the chest through the oesophageal hiatus in the diaphragm. There are two main types of hiatal hernias; sliding and rolling:

- Sliding hiatus hernia – The lower oesophageal sphincter slides superiorly. Reflux is a common complication, as the diaphragm is no longer reinforcing the sphincter.

- Rolling Hiatus Hernia – The lower oesophageal sphincter remains in place, but a part of the stomach herniates into the chest next to it. This type of hiatus hernia is more likely to require surgical correction to prevent strangulation of the herniated pouch.

Fig 6 – Classifications of hiatus hernias. is the normal anatomy, B is a pre-stage, C is a sliding hiatal hernia, and D is a rolling type.