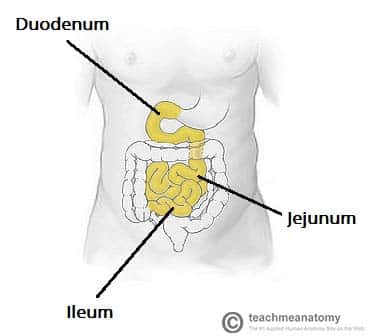

The small intestine is an organ located within the gastrointestinal tract. It is approximately 6.5m in the average person and assists in the digestion and absorption of ingested food.

It extends from the pylorus of the stomach to the ileocaecal junction, where it meets the large intestine at the ileocaecal valve. Anatomically, the small bowel can be divided into three parts: the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum.

In this article, we shall examine the anatomy of the small intestine – its structure, neurovascular supply, and clinical correlations.

The Duodenum

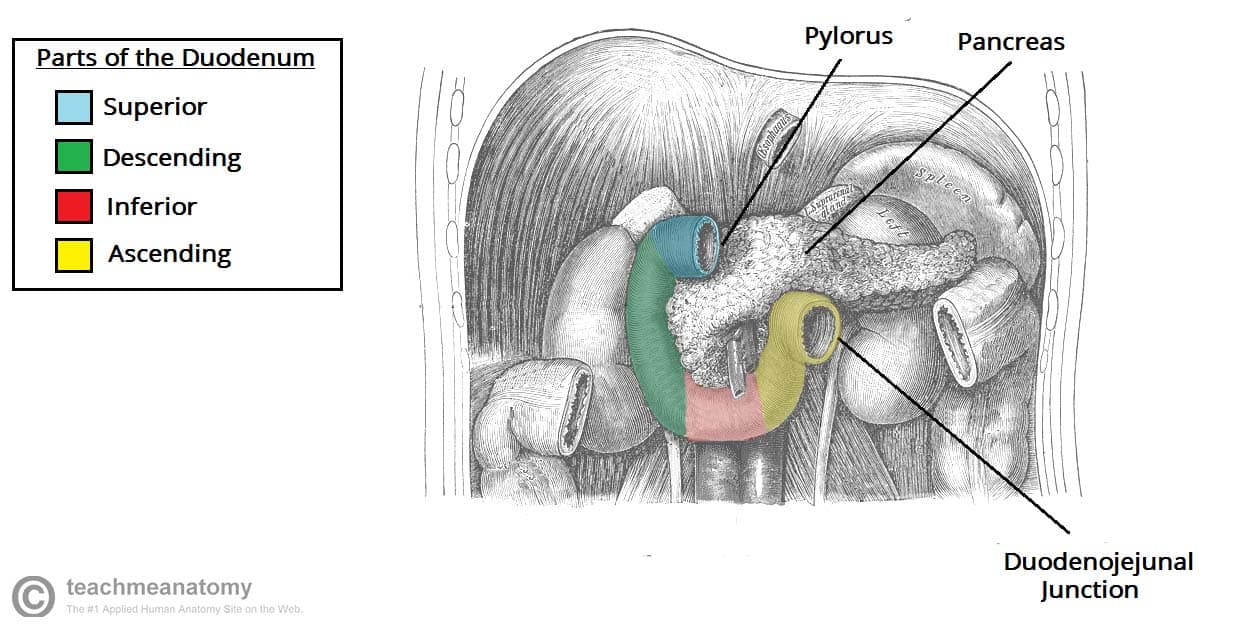

The most proximal portion of the small intestine is the duodenum. Its name is derived from the Latin ‘duodenum digitorum’, meaning twelve fingers length. It runs from the pylorus of the stomach to the duodenojejunal junction.

The duodenum can be divided into four parts: superior, descending, inferior and ascending. Together these parts form a ‘C’ shape, that is around 25cm long, and which wraps around the head of the pancreas.

D1 – Superior (Spinal level L1)

The first section of the duodenum is known as ‘the cap’. It ascends upwards from the pylorus of the stomach, and is connected to the liver by the hepatoduodenal ligament. This area is most common site of duodenal ulceration.

The initial 3cm of the superior duodenum is covered anteriorly and posteriorly by visceral peritoneum, with the remainder retroperitoneal (only covered anteriorly).

D2 – Descending (L1-L3)

The descending portion curves inferiorly around the head of the pancreas. It lies posteriorly to the transverse colon, and anterior to the right kidney.

Internally, the descending duodenum is marked by the major duodenal papilla – the opening at which bile and pancreatic secretions to enter from the ampulla of Vater (hepatopancreatic ampulla).

D3 – Inferior (L3)

The inferior duodenum travels laterally to the left, crossing over the inferior vena cava and aorta. It is located inferiorly to the pancreas, and posteriorly to the superior mesenteric artery and vein.

D4 – Ascending (L3-L2)

After the duodenum crosses the aorta, it ascends and curves anteriorly to join the jejunum at a sharp turn known as the duodenojejunal flexure.

Located at the duodenojejunal junction is a slip of muscle called the suspensory muscle of the duodenum. Contraction of this muscle widens the angle of the flexure, and aids movement of the intestinal contents into the jejunum.

Fig 2 – The different parts of the duodenum. The liver, gall bladder and transverse colon have been removed.

Clinical Relevance: Duodenal Ulcers

A duodenal ulcer is the erosion of the mucosa in the duodenum. It may also be described as a peptic ulcer (although this term can also be used to refer to ulcerations in the stomach). Duodenal ulcers are most likely to occur in the superior portion of the duodenum.

The most common causes of duodenal ulcers are Helicobacter pylori infection and chronic NSAID therapy.

An ulcer in itself can be painful, but is not particularly troublesome and can be treated medically. However, if the ulcer progresses to create a complete perforation through the bowel wall, this is a surgical emergency, and usually warrants immediate repair. A perforation may be complicated by:

- Inflammation of the peritoneum (peritonitis) – causing damage to the surrounding viscera, such as the liver, pancreas and gall bladder.

- Erosion of the gastroduodenal artery – causing haemorrhage and potential hypovolaemia shock.

Jejunum and Ileum

The jejunum and ileum are the distal two parts of the small intestine. In contrast to the duodenum, they are intraperitoneal.

They are attached to the posterior abdominal wall by mesentery (a double layer of peritoneum).

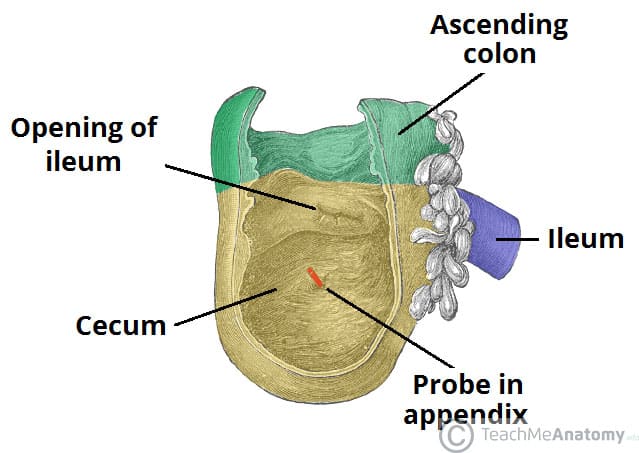

The jejunum begins at the duodenojejunal flexure. There is no clear external demarcation between the jejunum and ileum – although the two parts are macroscopically different. The ileum ends at the ileocaecal junction.

At this junction, the ileum invaginates into the cecum to form the ileocecal valve. Although it is not developed enough to control movement of material from the ileum to the cecum, it can prevent reflux of material back into the ileum (if patent, see below).

Clinical Relevance: Characteristic Features of the Jejunum and Ileum

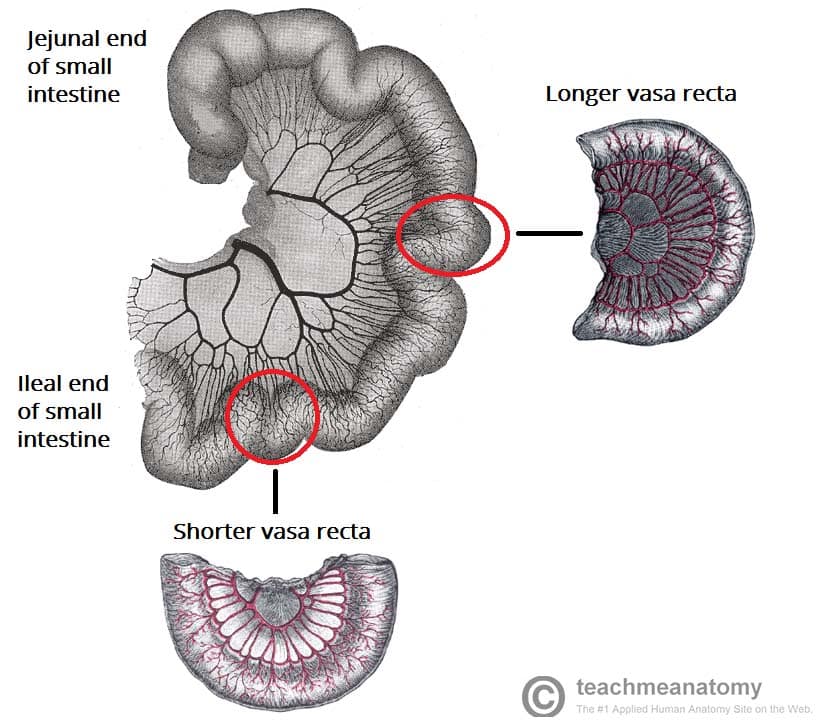

During surgery, it is often necessary to be able to distinguish between the jejunum and ileum of the small intestine:

| Jejunum | Ileum |

| Located in upper left quadrant | Located in lower right quadrant |

| Thick intestinal wall | Thin intestinal wall |

| Longer vasa recta (straight arteries) | Shorter vasa recta |

| Less arcades (arterial loops) | More arcades |

| Red in colour | Pink in colour |

Vasculature and Lymphatics

Duodenum

The arterial supply of the duodenum is derived from two sources:

- Proximal to the major duodenal papilla – supplied by the gastroduodenal artery (branch of the common hepatic artery from the coeliac trunk).

- Distal to the major duodenal papilla – supplied by the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery (branch of superior mesenteric artery).

This transition is important – it marks the change from the embryological foregut to midgut. The veins of the duodenum follow the major arteries and drain into the hepatic portal vein.

Lymphatic drainage is to the pancreatoduodenal and superior mesenteric nodes.

Jejunum and Ileum

The arterial supply to the jejunoileum is from the superior mesenteric artery.

The superior mesenteric artery arises from the aorta at the level of the L1 vertebrae, immediately inferior to the coeliac trunk. It moves in between layers of mesentery, splitting into approximately 20 branches. These branches anastomose to form loops, called arcades. From the arcades, long and straight arteries arise, called vasa recta.

The venous drainage is via the superior mesenteric vein. It unites with the splenic vein at the neck of the pancreas to form the hepatic portal vein.

Lymphatic drainage is into the superior mesenteric nodes.

Clinical Relevance: Ileocaecal valve

The ileocaecal valve represents the separation between the small and large intestine. Its main function is to prevent the reflux of enteric fluid from the colon into the small intestine. It is also used as an landmark during colonoscopy, indicating that the limit of the colon has been reached and that a complete colonoscopy has been performed.

The ileocaecal valve is also important in the setting of large bowel obstruction. Should the ileocaecal valve be competent, a closed loop obstruction can occur and cause bowel perforation. Should the ileocaecal valve be incompetent (i.e. allow backflow of enteric contents into the small bowel) then the situation is less emergent and the trajectory of the obstruction less rapid.