The oesophagus is a fibromuscular tube, approximately 25cm in length, that transports food from the pharynx to the stomach.

It originates at the inferior border of the cricoid cartilage (C6) and extends to the cardiac orifice of the stomach (T11).

In this article we shall examine the anatomy of the oesophagus – its structure, vascular supply and clinical correlations.

Anatomical Course

The oesophagus begins in the neck, at the level of C6. Here, it is continuous superiorly with the laryngeal part of the pharynx (the laryngopharynx).

It descends downward into the superior mediastinum of the thorax, positioned between the trachea and the vertebral bodies of T1 to T4. It then enters the abdomen via the oesophageal hiatus (an opening in the right crus of the diaphragm) at T10.

The abdominal portion of the oesophagus is approximately 1.25cm long – it terminates by joining the cardiac orifice of the stomach at level of T11.

Anatomical Structure

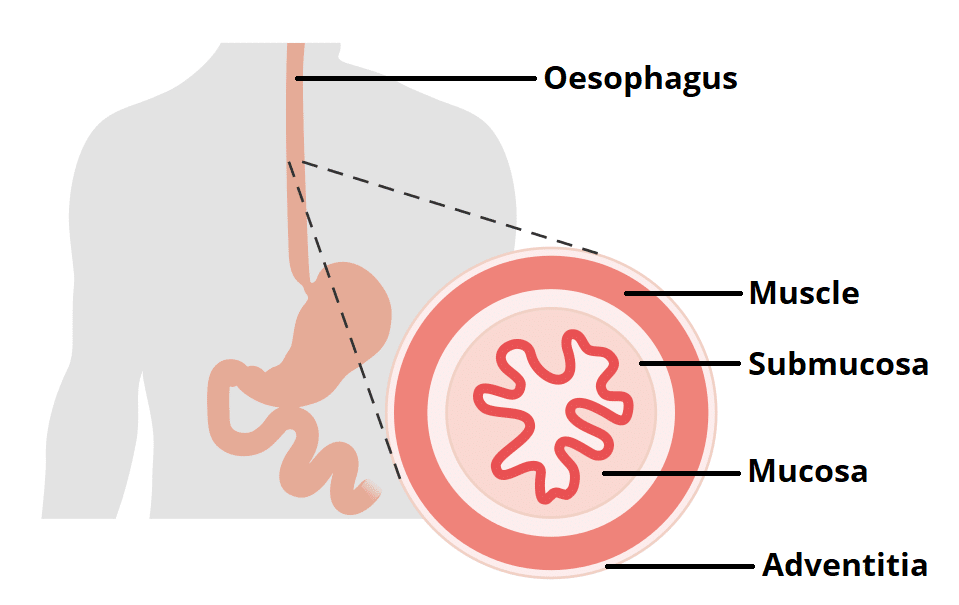

The oesophagus shares a similar structure with many of the organs in the alimentary tract:

- Adventitia – outer layer of connective tissue.

- Note: The very distal and intraperitoneal portion of the oesophagus has an outer covering of serosa, instead of adventitia.

- Muscle layer – external layer of longitudinal muscle and inner layer of circular muscle. The external layer is composed of different muscle types in each third:

- Superior third – voluntary striated muscle

- Middle third – voluntary striated and smooth muscle

- Inferior third – smooth muscle

- Submucosa

- Mucosa – non-keratinised stratified squamous epithelium (contiguous with columnar epithelium of the stomach).

Food is transported through the oesophagus by peristalsis – rhythmic contractions of the muscles which propagate down the oesophagus. Hardening of these muscular layers can interfere with peristalsis and cause difficulty in swallowing (dysphagia).

Fig 2 – The layers of the oesophagus. The muscle layer is further divided into an outer longitudinal layer and inner circular layer.

Oesophageal Sphincters

There are two sphincters present in the oesophagus, known as the upper and lower oesophageal sphincters. They act to prevent the entry of air and the reflux of gastric contents respectively.

Upper Oesophageal Sphincter

The upper sphincter is an anatomical, striated muscle sphincter at the junction between the pharynx and oesophagus. It is produced by the cricopharyngeus muscle. Normally, it is constricted to prevent the entrance of air into the oesophagus.

Lower Oesophageal Sphincter

The lower oesophageal sphincter is located at the gastro-oesophageal junction (between the stomach and oesophagus). The gastro-oesophageal junction is situated to the left of the T11 vertebra, and is marked by the change from oesophageal to gastric mucosa.

The sphincter is classified as a physiological (or functional) sphincter, as it does not have any specific sphincteric muscle. Instead, the sphincter is maintained by four factors:

- Oesophagus enters the stomach at an acute angle.

- Walls of the intra-abdominal section of the oesophagus are compressed when there is a positive intra-abdominal pressure.

- Prominent mucosal folds at the gastro-oesophageal junction aid in occluding the lumen.

- Right crus of the diaphragm has a “pinch-cock” effect.

During oesophageal peristalsis, the sphincter is relaxed to allow food to enter the stomach. Otherwise at rest, the function of this sphincter is to prevent the reflux of acidic gastric contents into the oesophagus.

Anatomical Relations

The anatomical relations of the oesophagus give rise to four physiological constrictions in its lumen – it is these areas where food/foreign objects are most likely to become impacted. They can be remembered using the acronym ‘ABCD‘:

- Arch of aorta

- Bronchus (left main stem)

- Cricoid cartilage

- Diaphragmatic hiatus

The table below lists the anatomical relations of the oesophagus:

| Anterior | Posterior | Right | Left | |

| Cervical and thoracic |

|

|

|

|

| Abdominal |

|

|

Vasculature

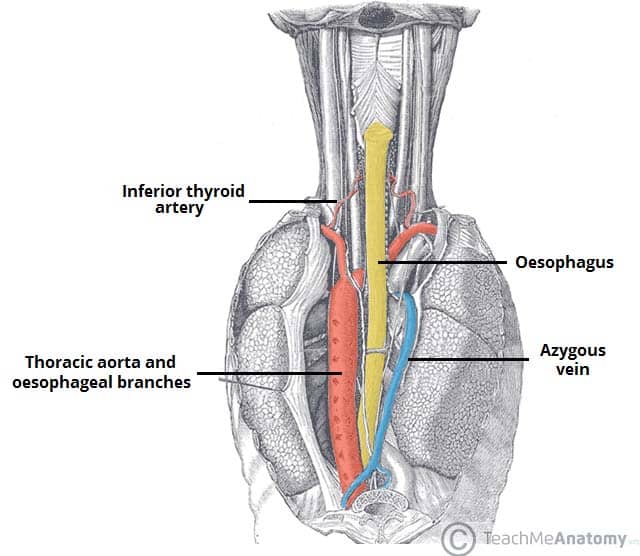

In respect to its arterial and venous supply, the oesophagus can be divided into its thoracic and abdominal components.

Thoracic

The thoracic part of the oesophagus receives its arterial supply from the branches of the thoracic aorta and the inferior thyroid artery (a branch of the thyrocervical trunk).

Venous drainage into the systemic circulation occurs via branches of the azygous veins and the inferior thyroid vein.

Abdominal

The abdominal oesophagus is supplied by the left gastric artery (a branch of the coeliac trunk) and left inferior phrenic artery. This part of the oesophagus has a mixed venous drainage via two routes:

- To the portal circulation via left gastric vein

- To the systemic circulation via the azygous vein.

These two routes form a porto-systemic anastomosis, a connection between the portal and systemic venous systems.

Fig 3 – Posterior view of the oesophagus. Some of the thoracic vasculature is noted.

Innervation

The oesophagus is innervated by the oesophageal plexus, which is formed by a combination of the parasympathetic vagal trunks and sympathetic fibres from the cervical and thoracic sympathetic trunks.

Two different types of nerve fibre run in the vagal trunks. The upper oesophageal sphincter and upper striated muscle is supplied by fibres originating from the nucleus ambiguus. Fibres supplying the lower oesophageal sphincter and smooth muscle of the lower oesophagus arise from the dorsal motor nucleus.

Lymphatics

The lymphatic drainage of the oesophagus is divided into thirds:

- Superior third – deep cervical lymph nodes.

- Middle third – superior and posterior mediastinal nodes.

- Lower third – left gastric and celiac nodes.

Clinical Relevance: Disorders of the Oesophagus

Barrett’s Oesophagus

Barrett’s oesophagus refers to the metaplasia (reversible change from one differentiated cell type to another) of lower oesophageal squamous epithelium to gastric columnar epithelium. It is usually caused by chronic acid exposure as a result of a malfunctioning lower oesophageal sphincter. The acid irritates the oesophageal epithelium, leading to a metaplastic change.

The most common symptom is a long-term burning sensation of indigestion.

It can be detected via endoscopy of the oesophagus. Patients who are found to have it will be monitored for any cancerous changes.

Oesophageal Carcinoma

Around 2% of malignancies in the UK are oesophageal carcinomas. The clinical features of this carcinoma are:

- Dysphagia – difficulty swallowing. It becomes progressively worse over time as the tumour increases in size, restricting the passage of food.

- Weight loss

There are two major types of oesophageal carcinomas: squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma.

- Squamous cell carcinoma – the most common subtype of oesophagus cancer. It can occur at any level of the oesophagus.

- Adenocarcinoma – only occurs in the inferior third of the oesophagus and is associated with Barrett’s oesophagus. It usually originates in the metaplastic epithelium of Barrett’s oesophagus.

Oesophageal Varices

The abdominal oesophagus drains into both the systemic and portal circulation, forming an anastomosis between the two.

Oesophageal varices are abnormally dilated sub-mucosal veins (in the wall of the oesophagus) that lie within this anastomosis. They are usually produced when the pressure in the portal system increases beyond normal, a state known as portal hypertension. Portal hypertension most commonly occurs secondary to chronic liver disease, such as cirrhosis or an obstruction in the portal vein.

The varices are predisposed to bleeding, with most patients presenting with haematemesis (vomiting of blood). Alcoholics are at a high risk of developing oesophageal varices.