The peritoneum is a continuous membrane which lines the abdominal cavity and covers the abdominal organs (abdominal viscera).

It acts to support the viscera, and provides pathways for blood vessels and lymph to travel to and from the viscera.

In this article, we shall look at the anatomy of the peritoneum – its structure, relationship with the abdominal organs, and any clinical correlations.

Structure of the Peritoneum

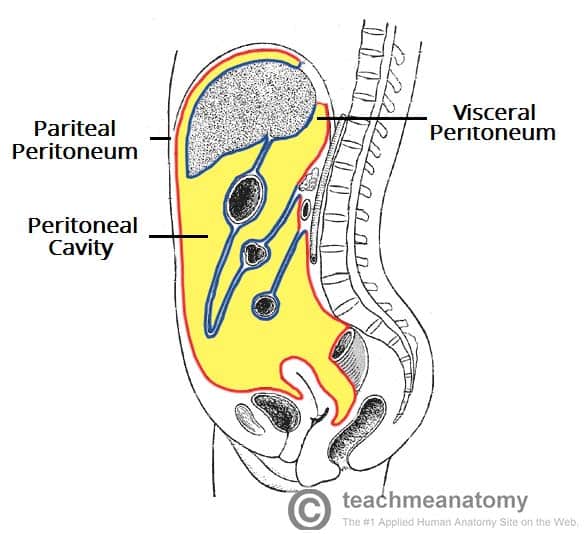

The peritoneum consists of two layers that are continuous with each other: the parietal peritoneum and the visceral peritoneum. Both types are made up of simple squamous epithelial cells called mesothelium.

Parietal Peritoneum

The parietal peritoneum lines the internal surface of the abdominopelvic wall. It is derived from somatic mesoderm in the embryo.

It receives the same somatic nerve supply as the region of the abdominal wall that it lines; therefore, pain from the parietal peritoneum is well localised. Parietal peritoneum is sensitive to pressure, pain, laceration and temperature.

Visceral Peritoneum

The visceral peritoneum invaginates to cover the majority of the abdominal viscera. It is derived from splanchnic mesoderm in the embryo.

The visceral peritoneum has the same autonomic nerve supply as the viscera it covers. Unlike the parietal peritoneum, pain from the visceral peritoneum is poorly localised and the visceral peritoneum is only sensitive to stretch and chemical irritation.

Pain from the visceral peritoneum is referred to areas of skin (dermatomes) which are supplied by the same sensory ganglia and spinal cord segments as the nerve fibres innervating the viscera.

Fig 1 – The structure of the peritoneum and the peritoneal cavity. Note how the visceral layer invaginates to cover the organs.

Peritoneal Cavity

The peritoneal cavity is a potential space between the parietal and visceral peritoneum. It normally contains only a small amount of lubricating fluid.

Clinical Relevance: Peritoneal Adhesions

Damage to the peritoneum can occur as a result of infection, surgery or injury.

The resulting inflammation and repair may cause the formation of fibrous scar tissue. This can result in abnormal attachments between the visceral peritoneum of adjacent organs or between visceral and parietal peritoneum.

Such adhesions can result in pain and complications such as volvulus, when the intestine becomes twisted around an adhesion resulting in a bowel obstruction.

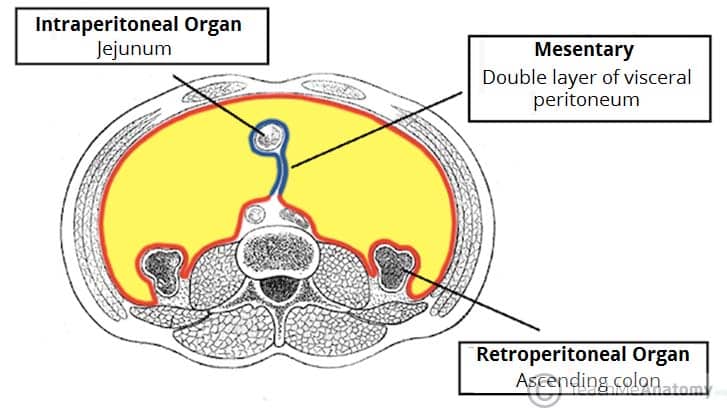

Intraperitoneal & Retroperitoneal Organs

The abdominal viscera can be divided anatomically by their relationship to the peritoneum. There are two main groups: intraperitoneal and retroperitoneal organs.

Intraperitoneal Organs

Intraperitoneal organs are enveloped by visceral peritoneum, which covers the organ both anteriorly and posteriorly. Examples include the stomach, liver and spleen.

Retroperitoneal Organs

Retroperitoneal organs are not associated with visceral peritoneum; they are only covered in parietal peritoneum, and that peritoneum only covers their anterior surface.

They can be further subdivided into two groups based on their embryological development:

- Primarily retroperitoneal organs developed and remain outside of the parietal peritoneum. The oesophagus, rectum and kidneys are all primarily retroperitoneal.

- Secondarily retroperitoneal organs were initially intraperitoneal, suspended by mesentery. Through the course of embryogenesis, they became retroperitoneal as their mesentery fused with the posterior abdominal wall. Thus, in adults, only their anterior surface is covered with peritoneum. Examples of secondarily retroperitoneal organs include the ascending and descending colon.

A useful mnemonic to help in recalling which abdominal viscera are retroperitoneal is SAD PUCKER:

- S = Suprarenal (adrenal) Glands

- A = Aorta/IVC

- D =Duodenum (except the proximal 2cm, the duodenal cap)

- P = Pancreas (except the tail)

- U = Ureters

- C = Colon (ascending and descending parts)

- K = Kidneys

- E = (O)esophagus

- R = Rectum

Peritoneal Reflections

The peritoneum covers nearly all viscera within the gut and conveys neurovascular structures from the body wall to intraperitoneal viscera.

In order to adequately fulfil its functions, the peritoneum develops into a highly folded, complex structure and a number of terms are used to describe the folds and spaces that are part of the peritoneum.

Mesentery

A mesentery is double layer of visceral peritoneum. It connects an intraperitoneal organ to (usually) the posterior abdominal wall. It provides a pathway for nerves, blood vessels and lymphatics to travel from the body wall to the viscera.

The mesentery of the small intestine is simply called ‘the mesentery’. Mesentery related to other parts of the gastrointestinal system is named according to the viscera it connects to, for example the transverse and sigmoid mesocolons, the mesoappendix.

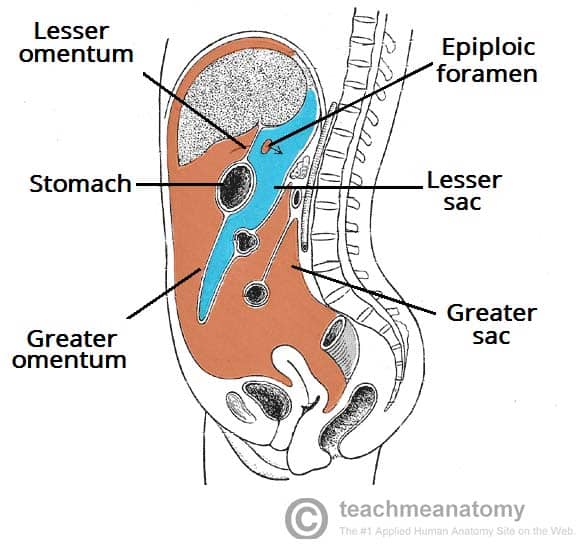

Omentum

The omenta are sheets of visceral peritoneum that extend from the stomach and proximal part of the duodenum to other abdominal organs.

Greater Omentum

The greater omentum consists of four layers of visceral peritoneum. It descends from the greater curvature of the stomach and proximal part of the duodenum, then folds back up and attaches to the anterior surface of the transverse colon.

It has a role in immunity and is sometimes referred to as the ‘abdominal policeman’ because it can migrate to infected viscera or to the site of surgical disturbance.

Lesser Omentum

The lesser omentum is a double layer of visceral peritoneum, and is considerably smaller than the greater and attaches from the lesser curvature of the stomach and the proximal part of the duodenum to the liver.

It consists of two parts: the hepatogastric ligament (the flat, broad sheet) and the hepatoduodenal ligament (the free edge, containing the portal triad).

Peritoneal Ligaments

A peritoneal ligament is a double fold of peritoneum that connects viscera together or connects viscera to the abdominal wall.

An example is the hepatogastric ligament, a portion of the lesser omentum, which connects the liver to the stomach.

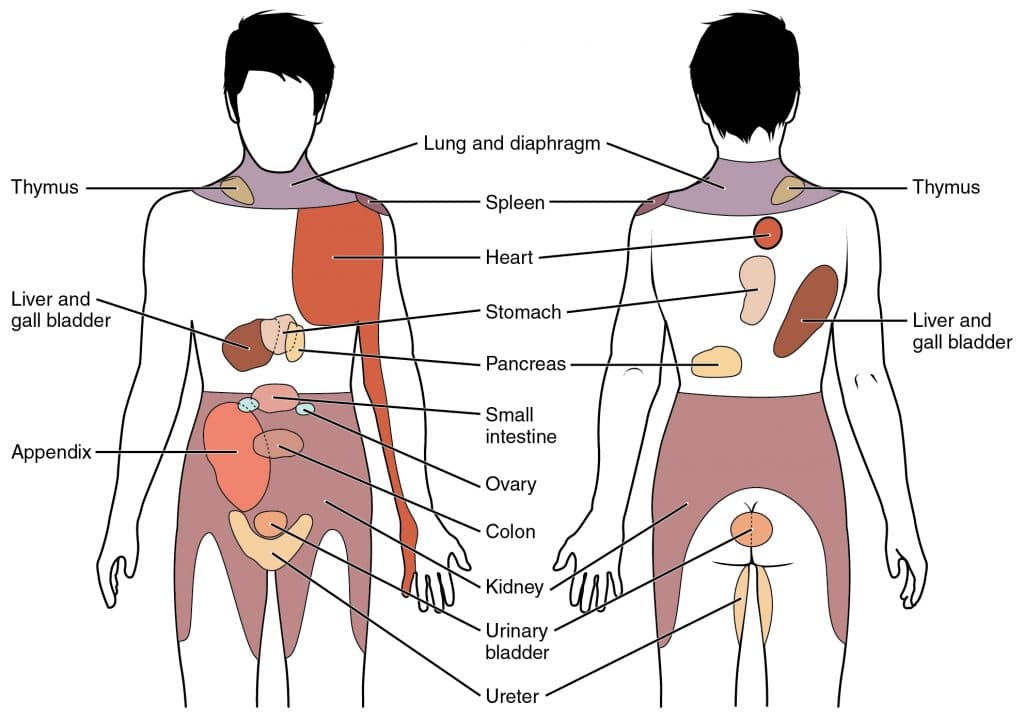

Clinical Relevance – Referred Pain

Pain from the viscera is poorly localised. As described earlier, it is referred to areas of skin (dermatomes) which are supplied by the same sensory ganglia and spinal cord segments as the nerve fibres innervating the viscera.

Pain is referred according to the embryological origin of the organ; thus pain from foregut structures are referred to the epigastric region, midgut structures are to the umbilical region and hindgut structures to the pubic region of the abdomen.

- Foregut – oesophagus, stomach, pancreas, liver, gallbladder and the duodenum (proximal to the entrance of the common bile duct).

- Midgut – duodenum (distal to the entrance of the common bile duct) to the junction of the proximal two thirds of the transverse colon with the distal third.

- Hindgut – distal one third of the transverse colon to the upper part of the anal canal.

Pain in retroperitoneal organs (e.g. kidney, pancreas) may present as back pain.

Irritation of the diaphragm (e.g. as a result of inflammation of the liver, gallbladder or duodenum) may result in shoulder tip pain.

Referred Pain in Appendicitis

Initially, pain from the appendix (midgut structure) and its visceral peritoneum is referred to the umbilical region. As the appendix becomes increasingly inflamed, it irritates the parietal peritoneum, causing the pain to localise to the right lower quadrant.