The femur is the only bone in the thigh and the longest bone in the body.

It acts as the site of origin and attachment of many muscles and ligaments, and can be divided into three parts; proximal, shaft and distal.

In this article, we shall look at the anatomy of the femur – its attachments, bony landmarks, and clinical correlations.

Premium Feature

3D Model

Proximal

The proximal aspect of the femur articulates with the acetabulum of the pelvis to form the hip joint.

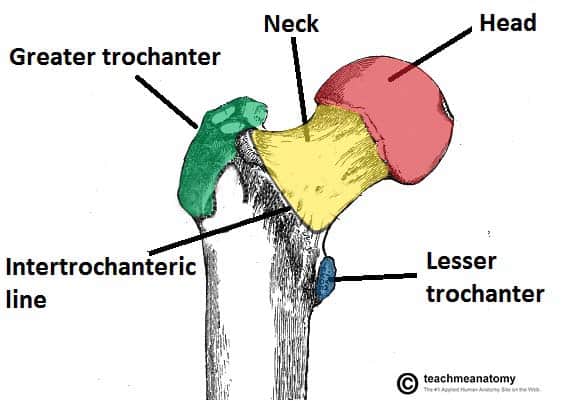

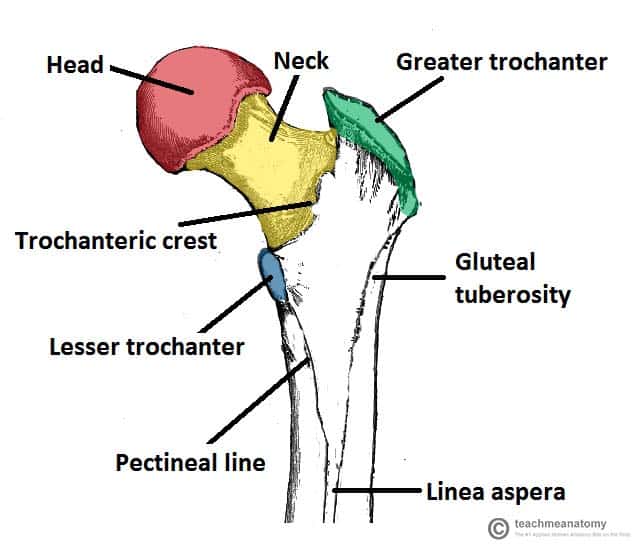

It consists of a head and neck, and two bony processes – the greater and lesser trochanters. There are also two bony ridges connecting the two trochanters; the intertrochanteric line anteriorly and the trochanteric crest posteriorly.

- Head – articulates with the acetabulum of the pelvis to form the hip joint. It has a smooth surface, covered with articular cartilage (except for a small depression – the fovea – where ligamentum teres attaches).

- Neck – connects the head of the femur with the shaft. It is cylindrical, projecting in a superior and medial direction. It is set at an angle of approximately 135 degrees to the shaft. This angle of projection allows for an increased range of movement at the hip joint.

- Greater trochanter – the most lateral palpable projection of bone that originates from the anterior aspect, just lateral to the neck.

- It is the site of attachment for many of the muscles in the gluteal region, such as gluteus medius, gluteus minimus and piriformis. The vastus lateralis originates from this site.

- An avulsion fracture of the greater trochanter can occur as a result of forceful contraction of the gluteus medius.

- Lesser trochanter – smaller than the greater trochanter. It projects from the posteromedial side of the femur, just inferior to the neck-shaft junction.

- It is the site of attachment for iliopsoas (forceful contraction of which can cause an avulsion fracture of the lesser trochanter).

- Intertrochanteric line – a ridge of bone that runs in an inferomedial direction on the anterior surface of the femur, spanning between the two trochanters. After it passes the lesser trochanter on the posterior surface, it is known as the pectineal line.

- It is the site of attachment for the iliofemoral ligament (the strongest ligament of the hip joint).

- It also serves as the anterior attachment of the hip joint capsule.

- Intertrochanteric crest – like the intertrochanteric line, this is a ridge of bone that connects the two trochanters. It is located on the posterior surface of the femur. There is a rounded tubercle on its superior half called the quadrate tubercle; where quadratus femoris attaches.

Clinical Relevance

Proximal Femur Fractures

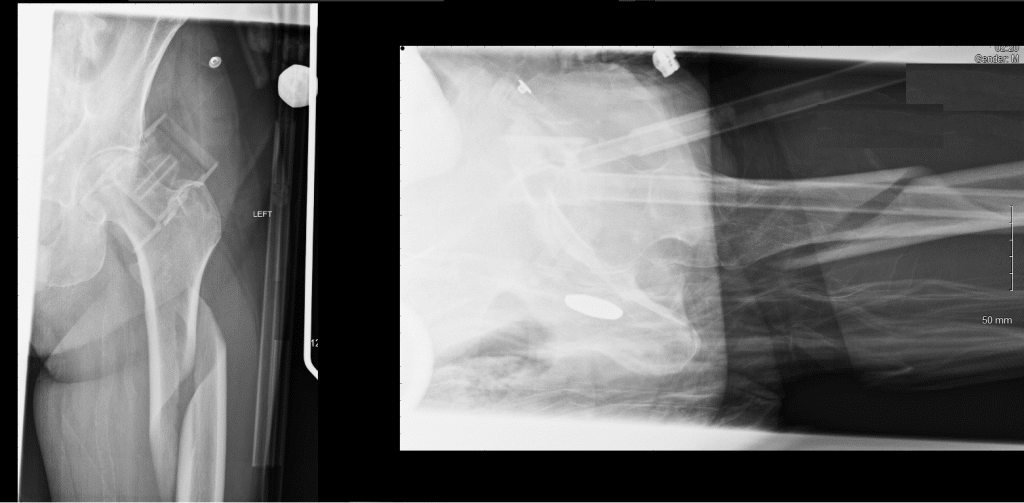

Neck of femur fractures (NOFs) are increasingly common and tend to be sustained by the elderly population as a result of low energy falls in the presence of osteoporotic bone. They are more prevalent in women. In younger patients they tend to occur as a result of high energy accidents.

The distal fragment is typically pulled upwards and rotated laterally. This manifests clinically as a shortened and externally rotated lower limb.

These fractures can be broadly classified into two main groups:

- Intracapsular – occurs within the capsule of the hip joint. It can damage the medial femoral circumflex artery – and cause avascular necrosis of the femoral head.

- Extracapsular – the blood supply to the head of femur is intact, so avascular necrosis is a rare complication.

The Shaft

The shaft of the femur descends in a slight medial direction. This brings the knees closer to the body’s centre of gravity, increasing stability. A cross section of the shaft in the middle is circular but flattened posteriorly at the proximal and distal aspects.

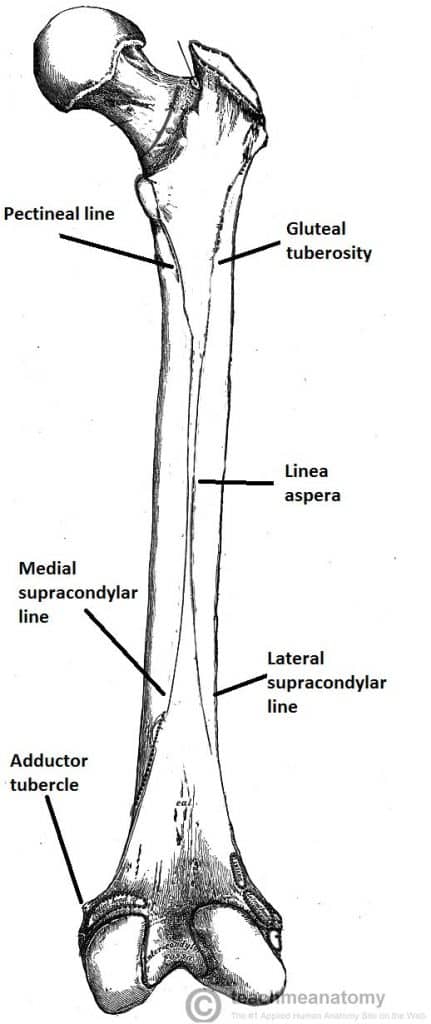

On the posterior surface of the femoral shaft, there are roughened ridges of bone, called the linea aspera (Latin for rough line). This splits distally to form the medial and lateral supracondylar lines. The flat popliteal surface lies between them.

Proximally, the medial border of the linea aspera becomes the pectineal line. The lateral border becomes the gluteal tuberosity, where the gluteus maximus attaches.

Distally, the linea aspera widens and forms the floor of the popliteal fossa, the medial and lateral borders form the medial and lateral supracondylar lines. The medial supracondylar line ends at the adductor tubercle, where the adductor magnus attaches.

Clinical Relevance

Fractures of the Femoral Shaft

Fractures of the femoral shaft are typically a high energy injury but can occur in the elderly as a result of a low energy fall.

They can often occur as a spiral fracture, which causes leg shortening. The loss of leg length is due the bony fragments overriding, pulled by their attached muscles.

As the method of injury is typically high energy, the surrounding soft tissues may also be damaged. Neurovascular structures at risk include the femoral nerve and artery. A closed femoral shaft fracture may result in considerable haemorrhage (1000-1500ml)

Distal

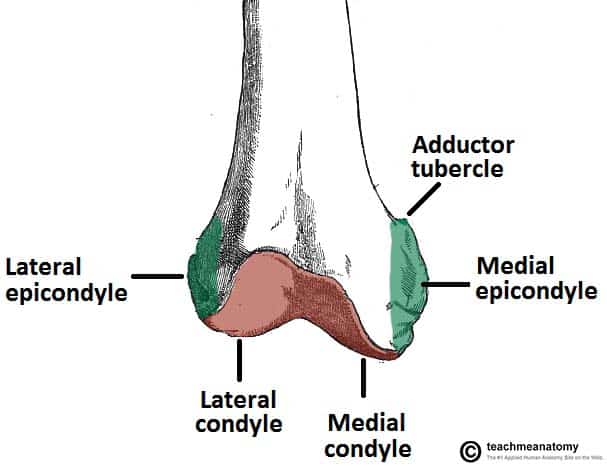

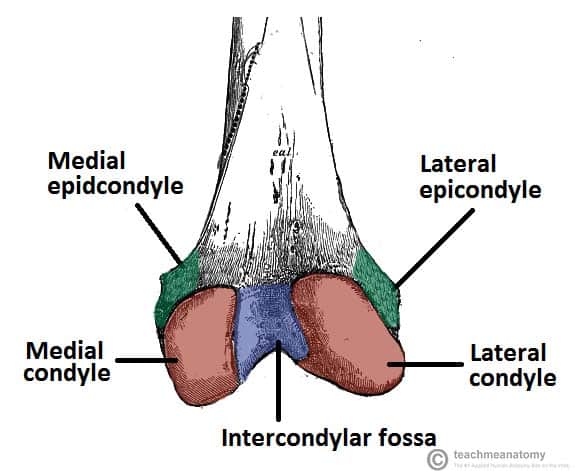

The distal end of the femur is characterised by the presence of the medial and lateral condyles, which articulate with the tibia and patella to form the knee joint.

- Medial and lateral condyles – rounded areas at the end of the femur. The posterior and inferior surfaces articulate with the tibia and menisci of the knee, while the anterior surface articulates with the patella. The more prominent lateral condyle helps prevent the natural lateral movement of the patella; a flatter condyle is more likely to result in patellar dislocation.

- Medial and lateral epicondyles – bony elevations on the non-articular areas of the condyles. The medial epicondyle is the larger.

- The medial and lateral collateral ligaments of the knee originate from their respective epicondyles.

- Intercondylar fossa – a deep notch on the posterior surface of the femur, between the two condyles. It contains two facets for attachment of intracapsular knee ligaments; the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) attaches to the medial aspect of the lateral condyle and the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) to the lateral aspect of the medial condyle.