The muscles of the shoulder are associated with movements of the upper limb. They produce the characteristic shape of the shoulder, and can be divided into two groups:

Extrinsic – originate from the torso, and attach to the bones of the shoulder (clavicle, scapula or humerus).

- Intrinsic – originate from the scapula and/or clavicle, and attach to the humerus.

Note: there are other muscles that act on the shoulder joint – the muscles of the pectoral region, and the upper arm.

In this article, we shall look at the anatomy of the intrinsic muscles of the shoulder – their attachments, innervation and actions.

The intrinsic muscles (also known as the scapulohumeral group) originate from the scapula and/or clavicle, and attach to the humerus.

There are six muscles in this group – the deltoid, teres major, and the four rotator cuff muscles (supraspinatus, infraspinatus, subscapularis and teres minor).

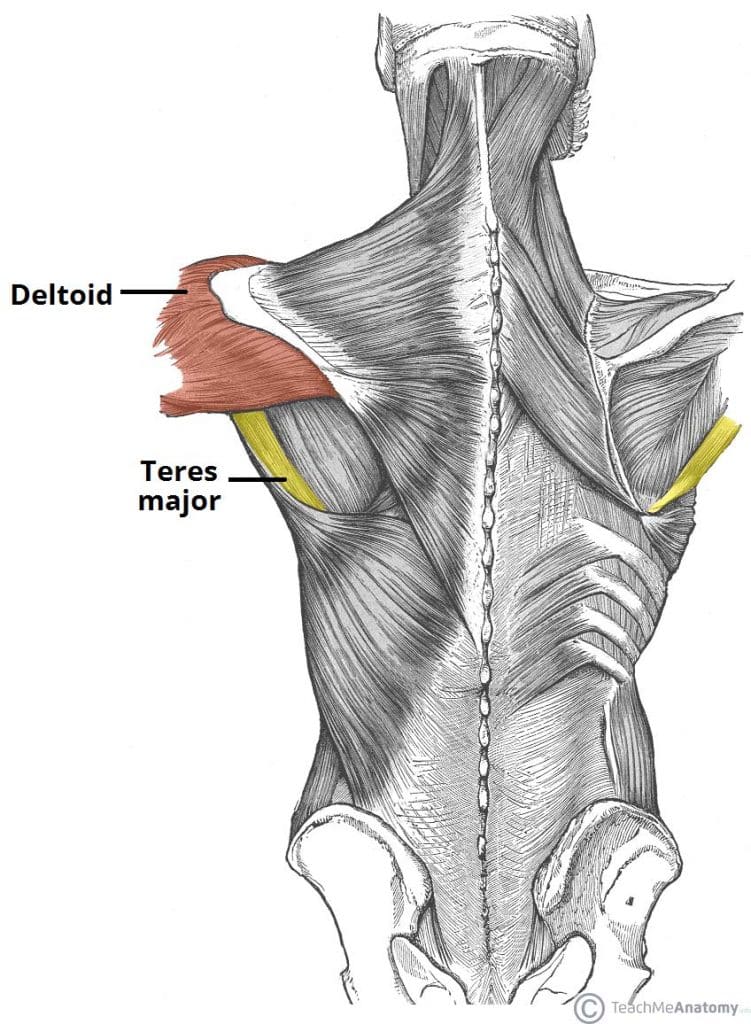

Deltoid

The deltoid muscle is shaped like an inverted triangle. It can be divided into an anterior, middle and posterior part.

- Attachments: Originates from the lateral third of the clavicle, the acromion and the spine of the scapula. It attaches to the deltoid tuberosity on the lateral aspect of the humerus.

- Actions:

- Anterior fibres – flexion and medial rotation.

- Posterior fibres – extension and lateral rotation.

- Middle fibres – the major abductor of the arm (takes over from the supraspinatus, which abducts the first 15 degrees).

- Innervation: Axillary nerve.

Teres Major

The teres major forms the inferior border of the quadrangular space – the ‘gap’ that the axillary nerve and posterior circumflex humeral artery pass through to reach the posterior scapular region.

- Attachments: Originates from the posterior surface of the inferior angle of the scapula. It attaches to the medial lip of the intertubercular groove of the humerus.

- Actions: Adducts and extends at the shoulder, and medially rotates the arm.

- Innervation: Lower subscapular nerve.

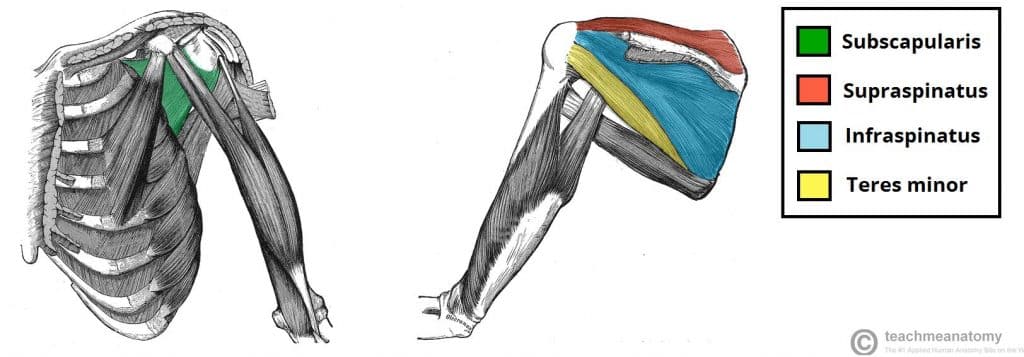

Rotator Cuff Muscles

The rotator cuff muscles are a group of four muscles that originate from the scapula and attach to the humeral head. Collectively, the resting tone of these muscles acts to ‘pull’ the humeral head into the glenoid fossa. This gives the glenohumeral joint a lot of additional stability.

In addition to their collective function, the rotator cuff muscles also have their own individual actions.

Supraspinatus

- Attachments: Originates from the supraspinous fossa of the scapula and attaches to the greater tubercle of the humerus.

- Actions: Abduction of the upper limb at the shoulder. It performs the first 0-15o of abduction, and assists the deltoid muscle for 15-90o

- Innervation: Suprascapular nerve.

Infraspinatus

- Attachments: Originates from the infraspinous fossa of the scapula, attaches to the greater tubercle of the humerus.

- Actions: Laterally rotates the arm.

- Innervation: Suprascapular nerve.

Subscapularis

- Attachments: Originates from the subscapular fossa, on the costal surface of the scapula. It attaches to the lesser tubercle of the humerus.

- Actions: Medially rotates the arm.

- Innervation: Upper and lower subscapular nerves.

Teres Minor

- Attachments: Originates from the posterior surface of the scapula, adjacent to its lateral border. It attaches to the greater tubercle of the humerus.

- Actions: Laterally rotates the arm.

- Innervation: Axillary nerve.

Fig 2 – The rotator cuff muscles, which act to stabilise the shoulder joint.

Clinical Relevance: Rotator Cuff Tendonitis

Rotator cuff tendonitis refers to inflammation of the tendons of the rotator cuff muscles. This usually occurs secondary to repetitive use of the shoulder joint.

The muscle most commonly affected is the supraspinatus. During abduction, it ‘rubs’ against the coraco-acromial arch. Over time, this causes inflammation and degenerative changes in the tendon itself.

Conservative treatment of rotator cuff tendonitis involves rest, analgesia, and physiotherapy. In more severe cases, steroid injections and surgery can be considered.