The external human face develops between the 4th and 6th week of embryonic development. The development of the face is completed by the 6th week.

Between the 6th and 8th week, the palate begins to develop. Consequently, this causes a distinction between the nasal and oral cavities. This development is completed by the 12th week.

In this article, we will outline the processes involved in the development of the face and palate. We will discuss the conditions associated with the complex development of these structures.

Background

There are two important tissue structures involved in development of the nose and face – the pharyngeal arches and neural crest cells.

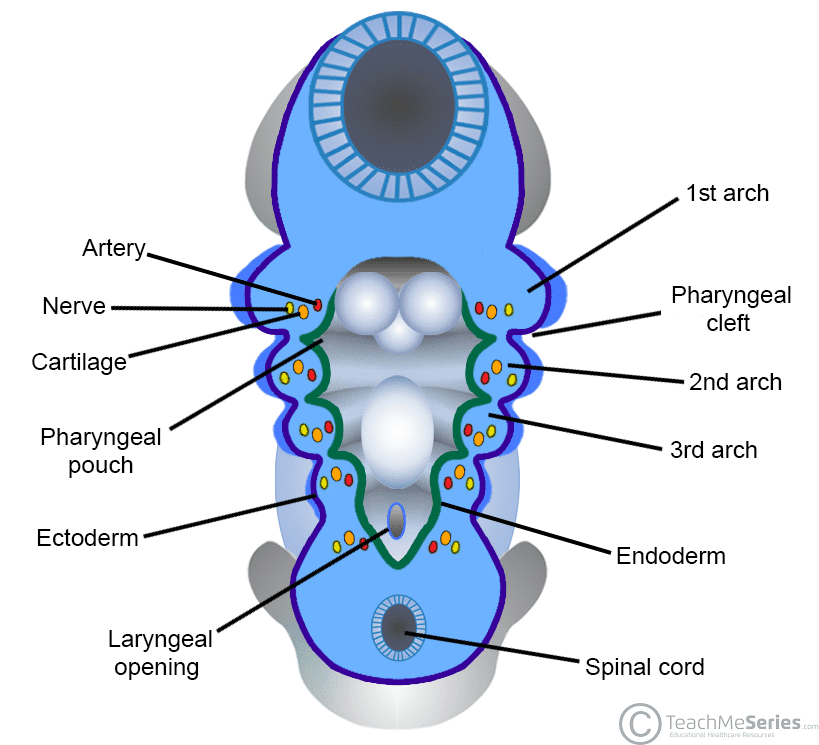

In the developing embryo, there are six pharyngeal arches. They arise in the fourth week of development as out-pocketings of mesoderm on both sides of the pharynx. Each pharyngeal arch has a branch of the aorta, a cranial nerve and a cartilage bar associated with it.

Neural crest cells are a specialised cell lineage which originate from neuroectoderm. As the neural tube forms, cells from the lateral border of the neuroectoderm are displaced into mesoderm, and from there they migrate throughout the body to form various structures. Of relevance to the head and neck, these cells enter the pharyngeal arches to help contribute to their derivatives.

Development of the Face

During week 3 of embryonic development, an oropharyngeal membrane initially appears at the site of the future face. It is comprised of ectoderm and endoderm – externally and internally, respectively.

During the 4th week, the oropharyngeal membrane begins to break down in order to become the future oral cavity, and sits at the beginning of the digestive tract.

The structures of the external face are derived from two sources:

- Frontonasal prominence – formed by the proliferation of mesenchymal neural crest cells ventral to the forebrain.

- Mandibular and maxillary prominences – parts of the 1st pharyngeal arch.

- A space lies between the maxillary prominences, covered by the oropharyngeal membrane; this is known as the stomatodeum, the precursor to the mouth and pituitary gland.

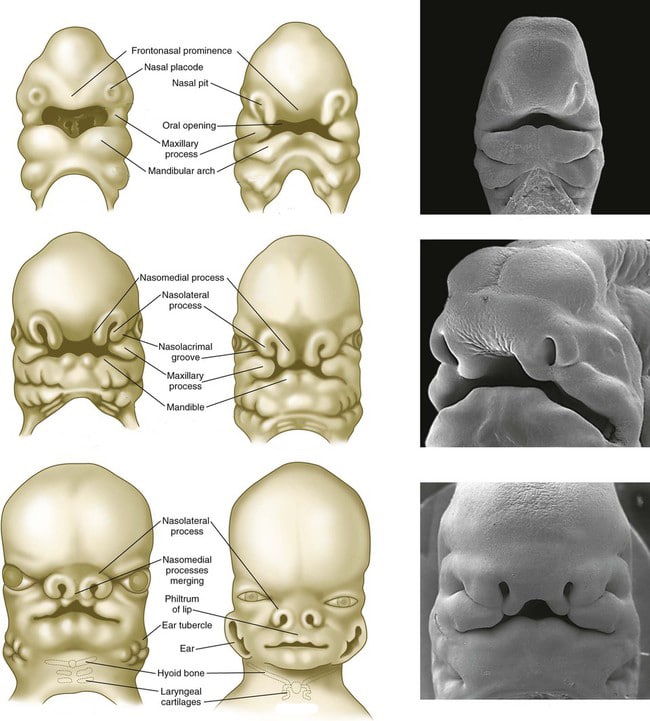

Nasal development is instigated by the appearance of raised bumps called nasal placodes on both sides of the frontonasal prominence. These then invaginate to form nasal pits, with medial and lateral nasal prominences on either side.

As the maxillary prominences expand medially, the nasal prominences are ‘pushed’ closer to the midline. The maxillary prominences then fuse with the nasal prominences – and soon after fuse in the midline to form a continuous central structure.

| Prominence | Derivatives |

| Frontonasal | Forehead, bridge of nose, medial and lateral nasal prominences |

| Medial nasal | Philtrum, primary palate, upper 4 incisors and associated jaw |

| Lateral nasal | Sides of the nose |

| Maxillary (1st pharyngeal arch) | Cheeks, lateral upper lip, secondary palate, lateral upper jaw |

| Mandibular (1st pharyngeal arch) | Lower lip and jaw |

Development of the Palate

Initially, the nasal cavity is continuous with the oral cavity. A series of steps lead to their separation, and the establishment of the palate.

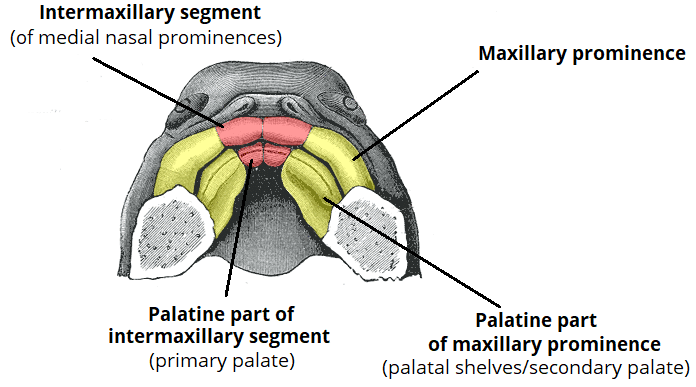

As the nose forms, the fusion of the medial nasal prominence with its contralateral counterpart creates the intermaxillary segment – which forms the primary palate (becomes the anterior 1/3 of the definitive palate). The intermaxillary segment also contributes to the labial component of the philtrum and the upper four incisors.

The maxillary prominences expand medially to give rise to the palatal shelves. These continue to advance medially, fusing superior to the tongue. Simultaneously, the developing mandible expands to increase the size of the oral cavity; this allows the tongue to drop out of the way of the growing palatal shelves. The palatal shelves then fuse with each other in the horizontal plane, and the nasal septum in the vertical plane, forming the secondary palate.

Fig 3 – Development of the palate from the intermaxillary segment and maxillary prominences

Clinical Relevance: Cleft Lip and Cleft Palate

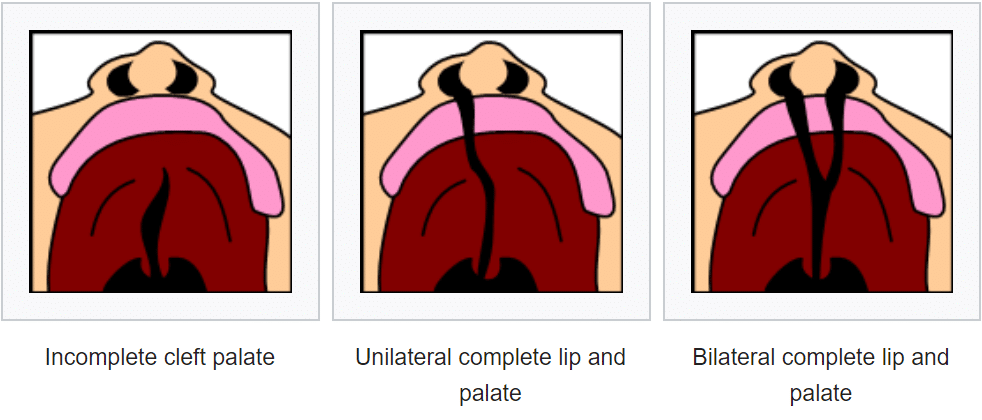

A cleft refers to a gap/split in the upper lip or palate. It results from a defect during development of face and palate:

- Cleft lip – occurs when the medial nasal prominence and maxillary prominence fail to fuse.

- Cleft palate – can occur in isolation when the palatal shelves fail to fuse in the midline, or in combination with cleft lip.

Cleft lip and cleft palate are relatively common, occurring in approximately 1/1000 births. In Native Americans, the rate is around 4 times that.

In addition to the cosmetic and psychosocial implications, severe cleft lip/palate can be a cause of death if a baby is unable to feed. Other complications include recurrent ear infections and speech impediment.